The story of Edward Snowden is a natural subject for Oliver Stone, a filmmaker who has made a specialty out of movies illustrating the potentially catastrophic effects of bureaucratic ambition and overreach.

Think back to Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko’s iconic “Wall Street” assertion that, “Greed is good,” or the way serving his country changed Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic, as depicted in “Born on the Fourth of July,” or the wild hypothesizing of “JFK,” and a picture emerges of a director engaged with the fashion in which sweeping currents of American life play out on both small and epic scales.

Snowden has come to symbolize the post-9/11 age in many respects, famously abandoning what seemed to be a comfortable life working as a National Security Agency contractor in Hawaii to disclose the global surveillance programs overseen by that organization and its counterparts in other countries.

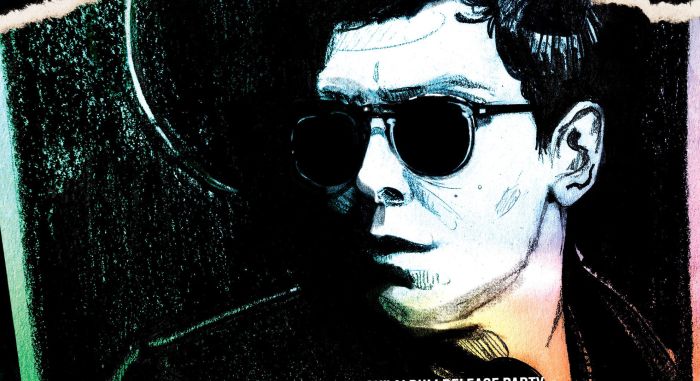

The movie “Snowden,” which dramatizes the protagonist’s rise through the CIA and eventually the NSA as set against his famous Hong Kong hotel room meetings with journalists Laura Poitras (Melissa Leo), Glenn Greenwald (Zachary Quinto) and Ewen MacAskill (Tom Wilkinson), has been made with a surprising degree of restraint given Stone’s characteristic propensity for sprawling cinematic flourishes.

It’s tinged with a hint of paranoia mixed with a serious consideration of a young man, just 29 years old when he began leaking to the press, who seems ordinary in most respects save for a stringent and uncompromising moral code.

But aside from virtuoso sequences depicting the streamlined visualizations of the surveillance operations, and periodically effective first-person touches, the movie develops at an emotional distance.

Star Joseph Gordon-Levitt infuses Snowden’s stoicism with a compelling degree of barely-contained outrage, but the picture fails when it comes to establishing a greater understanding of the emotional costs latent in making these sorts of life- and world-changing disclosures. Stone, who co-wrote the screenplay Kieran Fitzgerald, tries to make up some ground by paying great attention to domestic discord between Snowden and girlfriend Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley), but this story ought to transcend such relatively pedestrian dilemmas.

The movie must also struggle against the lofty, vivid memories of Poitras’ Oscar-winning documentary “Citizenfour,” the firsthand accounting of the encounter between Snowden and her fellow journalists in that hotel room circa June 2013.

It’s unfair to expect that Stone could have matched the compelling, real-life whistleblowing captured for posterity in that picture, the pervasive sense of danger that infuses it, the mysteries it presents in the persona at the center of it all.

He assembles the familiar events and fills in the backstory gaps with skill and smarts; there’s something to be said for chronicling this story with moderation, for the most part, rather than propagandistic passion. That’s an element largely missing from the ways it’s been depicted in the media and other facets of popular culture.

But, in the end, “Snowden” would have been better served by a healthy degree of Stone’s characteristic urgency and outrage. Maybe it’d have been messier, or wilder, but that’s what Stone does best.