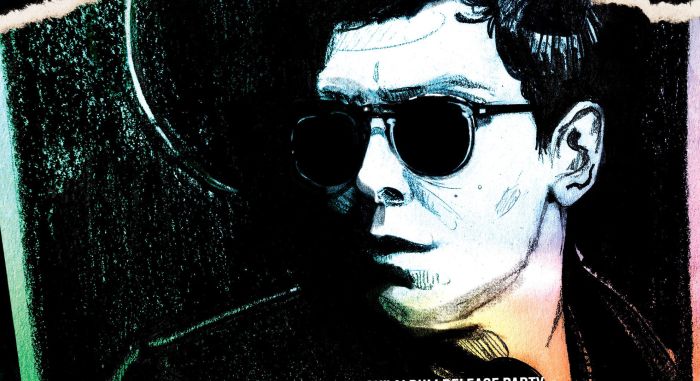

The title character of “Wilson” has total disregard for social norms. He’s that stranger on the bus who won’t stop talking to you; that friend who will give you his opinion about how technology’s ruining everything, whether you’ve asked for it or not.

As played by Woody Harrelson, he’s in every scene of Daniel Clowes’ adaptation of his graphic novel, directed by Craig Johnson (“The Skeleton Twins”). So the movie amounts to a referendum on his personality, in which the filmmakers and the star are tasked with complicating the protagonist to the point where it’s possible to have empathy for him, to understand the forces that created such a broken man.

It succeeds in fits and starts, but not enough to justify such a prolonged investment in this character. Harrelson injects notes of tangible vulnerability into his performance, but there’s only so much time one can spend listening to someone give his holier-than-thou perspective and whine about how victimized he’s been before desperately seeking an exit plan.

The picture finds Wilson on what amounts to a last-ditch quest to regain the happiness denied him. He reunites with his ex-wife Pippi (Laura Dern) and tries to forcibly create the family unit he never had when he learns that the daughter he thought Pippi aborted is in fact a teenager named Claire (Isabella Amara), living with her adopted family somewhere in generic suburbia.

The movie exists in a universe populated by the films of Terry Zwigoff, whose past includes the terrific Clowes adaptation “Ghost World,” and Alexander Payne. Those filmmakers stand as American cinema’s foremost chroniclers of the sardonically morose, but their best work centers its characters in the sort of larger perspective required to contextualize them.

There’s nothing in “Wilson” that approaches the sharp satiric vision of Payne’s “Sideways” and its depiction of California wine snobs; or the confusion of the first summer after high school, as captured in “Ghost World.” Here, the character is the whole show, the force of nature incensed by the blandness surrounding him. It’s not enough.