The tears along the tapestry that is the history of the United States are stark and unpleasant — ranging from a Civil War to natural disasters, pandemics, and attacks on home soil, to name just a few.

For most of this country’s existence as a free and independent nation, baseball never lagged far behind, stressing the intrinsic value of a trivial sport so ingrained into the American culture that it has often been looked upon to heal; providing an unmistakable and familiar red stitching upon the mosaic.

This Sept. 11 marks the 20th anniversary of the worst terrorist attack conducted upon American shores as nearly 3,000 people were killed in a calculated assault carried out by al-Qaeda as two planes struck the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, a third plane hit the Pentagon just outside Washington, D.C., and a fourth plane was heroically forced down in Shanksville, PA.

As a nation came to terms with the shock of the unthinkable happening in their proverbial backyards, mourning the loss of thousands, and the seemingly insurmountable task of trying to recover, baseball once again was not too far behind to help — ever so slightly — alleviate the pain that is still felt so deeply by so many two decades later.

And the New York Mets led the way.

‘Confusion’

Following a mostly difficult August, the defending National League champion Mets were surging at the right time in hopes of nabbing a spot in the 2001 playoffs. After taking two of three from the then-Florida Marlins, the Mets had won 10 of their last 12 and traveled from Miami to Pittsburgh on Sept. 10 for a three-game set against the Pirates.

“We get to Pittsburgh around 3 in the morning and when you travel, you go straight from the airport to the hotel and check-in, go to your room, and go to sleep,” Mets Hall of Famer and the team’s second baseman in 2001, Edgardo Alfonzo, said. “My wife knew that every time we traveled, we get in early in the morning. So it surprised me when she called at like, 9 in the morning.”

“‘Put the news on, something happened,'” Alfonzo recounted his wife telling him.

The first plane had just struck the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

“I turned on the TV and I caught the news between the first and second airplane strikes,” former first baseman Todd Zeile, who was two days removed from his 36th birthday, said. “At first, it seemed like a really bizarre, random story of a plane out of its flight path ending up in the tower, and then watching live as the second one struck, it became a totally different feeling.”

So sunk in the reality that the United States was under attack.

“It was a feeling of confusion, a feeling of dread. I don’t think anyone really anticipated at that time what was going on. It was ‘wait, how is this possible?'” Zeile said. “There’s confusion when you’ve grown up without that kind of activity on your own shore and I think that was, to me, what resonated. We’ve heard about terrorist activity all over the world but it never has been at home.

“And it was literally at home. I was living in New York and a part of this Mets team and I felt a part of this city.”

So did most of the Mets, most particularly pitchers John Franco, from Brooklyn, and Al Leiter, from Toms River, NJ.

“Johnny tried calling home, the line was out, the service was off completely,” Alfonzo said. “It was scary.”

While glued to their television sets at the Westin Hotel, which was connected to the William S. Moorhead Federal Building, it was discovered that Flight 93 — which took off from Newark, NJ — veered off course and was heading toward the Pittsburgh area, prompting the Mets to evacuate from the hotel.

“We went to a hotel up in the mountains and we were wondering ‘what are we going to do here?'” Alfonzo said. “So we were waiting to see what the next move was for us.”

Over the next hour, the towers collapsed, Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon, and Flight 93 went down in that field in Shanksville.

“We were thinking ‘is this really this widespread and calculated?'” Zeile wondered. “For the rest of that morning, day, and into the night, we were wondering if there were other things that were going to happen and there was a feeling of nervousness and confusion.

“You couldn’t take your eyes off the screen thinking of the devastation that occurred and how we were going to recover from it. There was also an element of confusion of ‘where were we going to go?’ ‘How were we going to get there?'”

Finding Their Way Home

With the airports shut down, the Mets were able to get a pair of busses on the night of Sept. 11 to take them back to New York — a trip that will forever stick in the minds of every player and staff member on board.

“I remember being quiet and generally MLB bus rides aren’t quiet,” starting pitcher Glendon Rusch, who was 26 at the time, said. “Many of the times we travel, everyone has a pretty good time, but this one was quiet. Very somber and everyone was in disbelief…I don’t think anyone knew how to handle that situation with us being in our 20s and 30s.”

“There had been talking on the way home that was different than anything ever discussed on a major-league or minor-league bus ride,” Zeile added. “I think there was a camaraderie that was building, and then we got to the bridge.”

The George Washington Bridge provides one of the most breathtaking views of lower Manhattan but as the seven-hour trip entered the heart of New York City at roughly 2 a.m., only more weight was added to the gravity of the situation.

“I remember seeing fire and smoke and wreckage from a distance,” Rusch said. “That area was kind of aglow with fire and orange… Very sad to see what was going on and it only got worse once we really took in the magnitude of what was happening.”

For Zeile, what happened inside the bus was just as impactful as what the Mets saw outside.

“Everyone crowded to the right side of the bus and you could hear a pin drop,” he said. “Looking down where the towers had been and you’re seeing floodlights shining up into the sky, illuminating the smoke that was still billowing… you could smell what smelled like an electrical fire. That sort of burning smell that I’ll never forget. The silence was broken only by the sound of emotion — tears by some of the guys that had direct, personal connections to the city.”

“I was devastated,” Alfonzo added.

Getting To Work

Shea Stadium, the former home of the Mets, was just 16 miles away from Ground Zero and was viewed as a vital landmark with the space and capacity to help relief efforts.

“I think a lot of people aren’t aware but initially, Shea Stadium was set up as a triage center for the recovery of victims,” Zeile said. “Essentially, a morgue — a holding center for the recovery effort because of some specific things that were a part of Shea in terms of refrigeration and so on.”

As days passed, however, it became clear that there were no bodies to recover.

While players and staff alike took time to go home and check on their families, Mets manager Bobby Valentine was determined to use his team as a vehicle to help the first responders and rescue workers excavating the site.

Players unloaded supplies ranging from work boots, water bottles, and batteries, packed boxes, and stocked up trucks that would be sent to Ground Zero.

“There were a lot of Mets fans in that situation and you want to give back to them what they give back to you — the love. You want to help them out at that moment,” Alfonzo said. “That was really hard, really sad.”

In an attempt to boost morale, Zeile, along with Mike Piazza, Robin Ventura, Franco, and Leiter went to Ground Zero to visit those first responders — entering a restricted zone of the city that encapsulated a 30-to-40-block radius.

“I remember feeling this feeling of panic in a sense of ‘Why am I here? What do these people want to see me for?'” Zeile wondered. “I felt it was almost invasive. A guy that plays baseball for a job is coming in with another group of guys that play baseball as a job. To think that we can understand even for a second what these guys are going through, I felt a little nervous about being invasive into their world and what they were going through.”

That anxiety quickly dissipated.

“The first of the first responders that we saw, we could see a total change in their face when he saw the guys in their Mets hats,” he said. “It was an instantaneous break from what they were going through for a week at that time. That put us at ease and gave us some feeling of purpose.

“If nothing else, maybe we gave these guys a few minutes to kind of take a break from the absolute trauma that they must be feeling and looking through this rubble for bodies of their friends, people they lost, people they’re unsure about what they’re going to find.”

Back To Baseball

There had been mixed sentiments from even some players on whether or not Major League Baseball should continue the 2001 season after Sept. 11, but one resounding voice helped ease any uncertainties.

“At first, I thought the season would end at that time, but then [President George Bush] said let’s get back to playing,” Alfonzo said. “That moment was like, wow, this is going to be hard, but let’s play baseball.”

Even more difficult was that the Mets had to go back to Pittsburgh to resume their series against the Pirates from Sept. 17-19 after nearly a week of trying to help New York through the aftermath of its worst moments.

They took a bit of their Big Apple family with them, though, as Zeile famously traded a “hat for a hat,” receiving a navy blue FDNY cap from the son and the widow of a rescue worker who died at the World Trade Center just days earlier. It sparked a movement that saw the Mets don the caps of all the first-responder branches, including the FDNY and NYPD.

“That became a tiny little symbolic gesture that this team was able to put forward for our appreciation of what those guys were doing while we were getting ready to play baseball again,” Zeile said.

react to the playing of the Star Spangled Banner before their baseball

game with the Pittsburgh Pirates, in Pittsburgh September 17, 2001.

Valentine is holding a New York Police Department hat in memory of the

victims of the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center.REUTERS/David DeNoma

Rusch, who started the third game of Mets’ series in Pittsburgh noted how warm the away fans welcomed his team, and how pitching in the first two innings of it was such a challenge.

“It really challenged every bit of what we did as players to focus on what was on the baseball field,” he said. “It really was difficult. I don’t remember anything that was as challenging as trying to take your focus off of what was going on in the world then and in our city and our country and focus on playing a baseball game. That was a challenge in itself.

“I think at that time, I don’t know if everybody was really that hyped to start playing again. I think we wanted to play just to give us a break, but it was a difficult transition.”

Shea Healing

Baseball eventually returned to New York on the night of Sept. 21 at Shea Stadium, just 10 days after the attacks.

“I think we all had some questions about whether or not people would feel comfortable showing up,” Zeile said. “It’s right next to LaGuardia [Airport], there’s all the fear of airplanes, another attack — all those things that were permeating throughout the country.

“Once we knew Mayor [Rudy] Giuliani and the city and the authorities felt like we were in a position that we could be safe and make a symbolic gesture to be back on the field and I think we were all ready for it.”

If there was any fear from the fans, it was not noticed. Rusch described the atmosphere as “electric,” as Diana Ross and Liza Minelli sang the national anthem and ‘God Bless America,’ throughout an evening that allowed New Yorkers to let loose, even if just for a moment.

“I think it was a huge part in helping to heal people. That was cool,” Rusch said. “We all felt proud that we were back and giving those people who had a lot of bad stuff going on in their life a bit of an escape. “

against the Atlanta Braves in New York, September 21, 2001. This is the

first baseball game to be held in New York since the attacks on the

World Trade Center September 11.REUTERS/Mike Segar

“You wanted to cry, you wanted to hug people, you wanted to applaud the fans,” Alfonzo added. “All those fans cheering, chanting ‘USA, USA’… and all this against the Braves? Our rival? That was amazing.”

But the Mets, who at the time were 4.5 games behind the Braves in the NL East, found themselves trailing 2-1 heading into the bottom of the eighth after Brian Jordan smacked a run-scoring double in the top half of the frame.

“The rest, you can say is serendipitous history,” Zeile said.

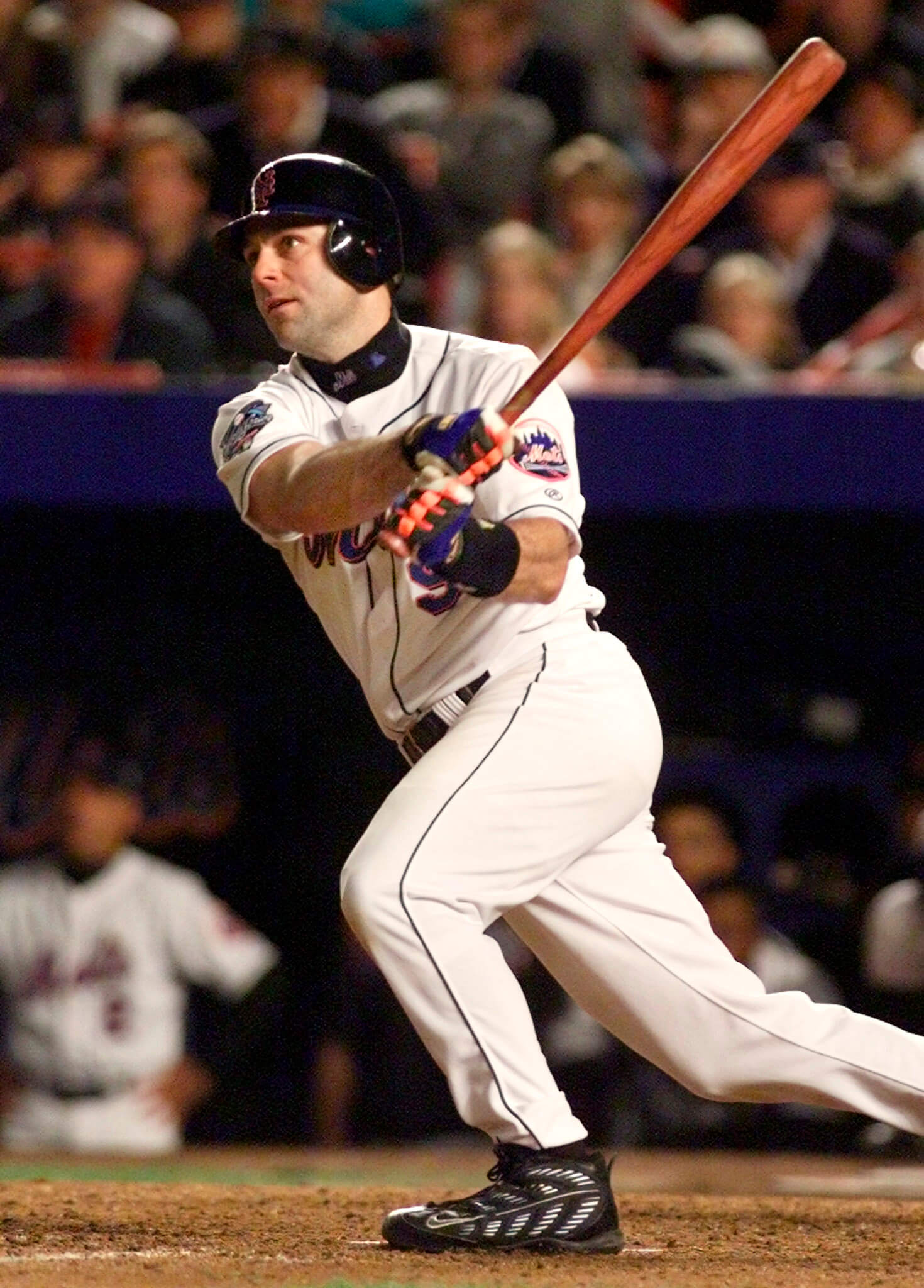

With one out against reliever Steve Karsay, Alfonzo walked and was pinch-run for by Desi Relaford, though speed on the basepaths would not matter as Piazza hit one of the most famous home runs in New York baseball history — a two-run shot to center field to put the Mets up for good.

“We did that,” Alfonzo said. “After I got a pinch-runner for me after I walked and I was on the bench and I saw Mike hit that ball out, what else could you ask for?”

In terms of a storybook baseball finish, not much.

It was the most memorable moment of a Mets season that ultimately ended short of making the playoffs. Meanwhile, it took years for the cleanup of Ground Zero to truly feel complete, though the emotional scars will never be erased.

Yes, in the grand scheme of things, it’s just a game. But in a city like New York, it’s an institution, a family, a place to heal.

“I’m proud of that team. I’ve been with 11 teams, played 16 years in the big leagues, I’ve been to the World Series, been to the playoffs, been on some really great teams,” Zeile said. “But that time in New York City was the most special time in my major-league career and that game on the 21st was without question — if someone asked me what my favorite moment — and it’s hard to say it’s your favorite given the circumstances surrounding it. But it’s certainly the most impactful, important baseball game I’ve ever played and probably the clearest memory I have of that experience as a major-league baseball player and I’m proud and privileged to have been a part of it.”