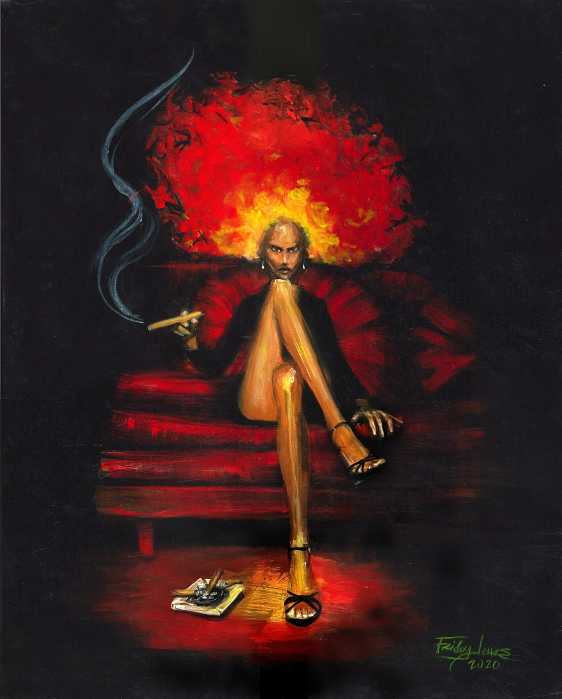

There are women who enter the art world like guests, waiting to be invited in. Then there are women like Tracey Emin, who storm the gates barefoot, cigarette in hand, dragging their past behind them like a weapon.

From the moment she emerged onto the scene in the early 1990s, Emin refused to perform femininity as palatable. She was not interested in pleasing the eye—she was determined to pierce it. In a climate still recovering from the rigidity of postmodernism and the masculine bravado of the 1980s art market, Emin offered something far more radical: the naked truth.

What she brought was not only a new aesthetic, but a new ethic—one forged in vulnerability, feminist intellect, and deeply autobiographical fire.

Tracey Emin did not emerge in isolation. She was forged in the turbulent aftermath of Thatcherism, against the backdrop of a nation where class and cultural identity were under dramatic negotiation. As a child of working-class Margate, Emin brought a regional and gendered voice to a London art scene still dominated by old hierarchies.

Her formal education at the Royal College of Art refined her technical fluency, yet it was her participation in the rise of the Young British Artists (YBAs) that positioned her as both insurgent and innovator. While her male contemporaries often veered toward sensationalism and bravado, Emin made the radical choice to turn inward. Her provocations were not performative; they were personal, immediate, and disarming in their candor.

Her inclusion in the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1997 marked her public emergence, although her true defiance had long been underway. My Bed (1998)—a work that continues to polarize—was neither an act of exhibitionism nor a cry for shock. Rather, it was a precise and deliberate act of feminist intervention.

By presenting the physical remains of a depressive episode—used underwear, cigarette butts, disheveled sheets—Emin challenged the sanctity of aesthetic distance. She transformed the private into the monumental and claimed a place in a canon that had historically excluded women’s emotional realities. Her bed did not ask to be interpreted; it demanded to be understood.

In this act, she aligned herself with a legacy of women artists—Carolee Schneemann, Louise Bourgeois, Ana Mendieta—who centered the body and interiority as valid and vital material. Emin, however, refracted these influences through a uniquely British lens, marked by sardonic humor, existential weariness, and a refusal to be pitied.

Her practice, which seamlessly weaves drawing, text, video, embroidery, and sculpture, dismantles the traditional boundaries between media and subjectivity. In her neon works, handwritten sentiments glow like distilled confessions. These are not slogans. They are elegies. Each one a quiet rebellion against the assumption that intellect must arrive devoid of feeling.

Critics have often struggled with Emin’s refusal to separate the autobiographical from the conceptual. The accusation of narcissism—a charge rarely leveled at her male peers—fails to grasp the criticality of her position. Emin’s art is not indulgent; it is architectural. She constructs spaces for empathy, grief, and feminine agency with the precision of an emotional engineer. Her studio is a site of excavation—of memory, loss, and longing—and she invites the viewer not to judge, but to witness.

Emin’s evolution over the past two decades has only deepened her impact. Recent works—haunting, spare, and profoundly introspective—explore mortality, solitude, and the fragile architecture of the soul. These are not the gestures of an artist mellowing with age. They are the expressions of a woman who has earned her silence, sharpened her vision, and refined her tools. Her legacy is palpable in a new generation of women artists who do not ask for permission to speak, who make the personal a site of political and intellectual discourse.

Tracey Emin did not merely enter the art world. She reshaped its contours. Through radical vulnerability and unflinching candor, she carved a space for complexity, contradiction, and emotional intellect. Her work insists that the female experience—not just in its beauty, but in its ache and ambiguity—is worthy of reverence and critical engagement.

She remains, to this day, a force—less a comet than a constellation—guiding those who dare to tell the truth through their art, regardless of whether that truth is palatable.

To read more reflections at the intersection of art, autonomy, and the aesthetic avant-garde, I invite you to visit avalonashley.com—a curated portal for the culturally ravenous and the intellectually restless.