BY CARLOTTA MOHAMED

As the weeks of stay-at-home orders and school closures continue amid the coronavirus pandemic, many families who have children with special needs are enduring the suspension of both school and essential services that their children are used to receiving.

For Forest Hills resident Rachel Sokol, it’s been quite challenging as a mother taking on the role of a therapist to help her 2-year-old daughter, Aimee, who is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is non-verbal.

Autism, or ASD, refers to a broad range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, speech and non-verbal communication.

In Aimee’s case, she struggles with communication, articulation, attention and things that should come to her with ease — such as making eye contact, pointing, drinking from a straw and shaking her head yes or no. She also makes loud grunting noises instead of baby babble, according to Sokol.

“Aimee doesn’t remember how to use a spoon correctly, and it’s only been a month because she hasn’t had her therapies,” Sokol said. “I’ve been doing puzzles with her and speech, trying to control her. Without her therapists, I’ve seen a regression in my daughter.”

Following the shutdown of New York City public schools on March 15 due to the coronavirus outbreak, Aimee’s therapists were considered non-essential services, according to Sokol.

“I can’t even imagine kids in wheelchairs, kids with MS, or even kids with severe social issues, who don’t have therapists working with them,” Sokol said. “Now their parents are homeschooling them and they have to become therapists overnight. I don’t know how to be a therapist.”

Diagnosed with ASD in August 2019, Aimee began receiving therapy services through the city’s program called Early Intervention, where eligible children — infants and toddlers — with developmental delays and disabilities learn many key skills and catch up in their development.

Aimee works with six therapists for ABA, speech, physical therapy and occupational therapy. Her time is split between two sensory gyms in Queens and four therapists visiting her at home, according to Sokol.

“She learned how to wave, brush her own teeth, nod and shake her head. Her tantrums decreased, her eye contact was better, and she was able to point,” Sokol said. “I saw such a change in her and said, ‘Oh my god, there’s hope for her at the end of the tunnel,’ and then COVID-19 struck followed by the city shutdown.’”

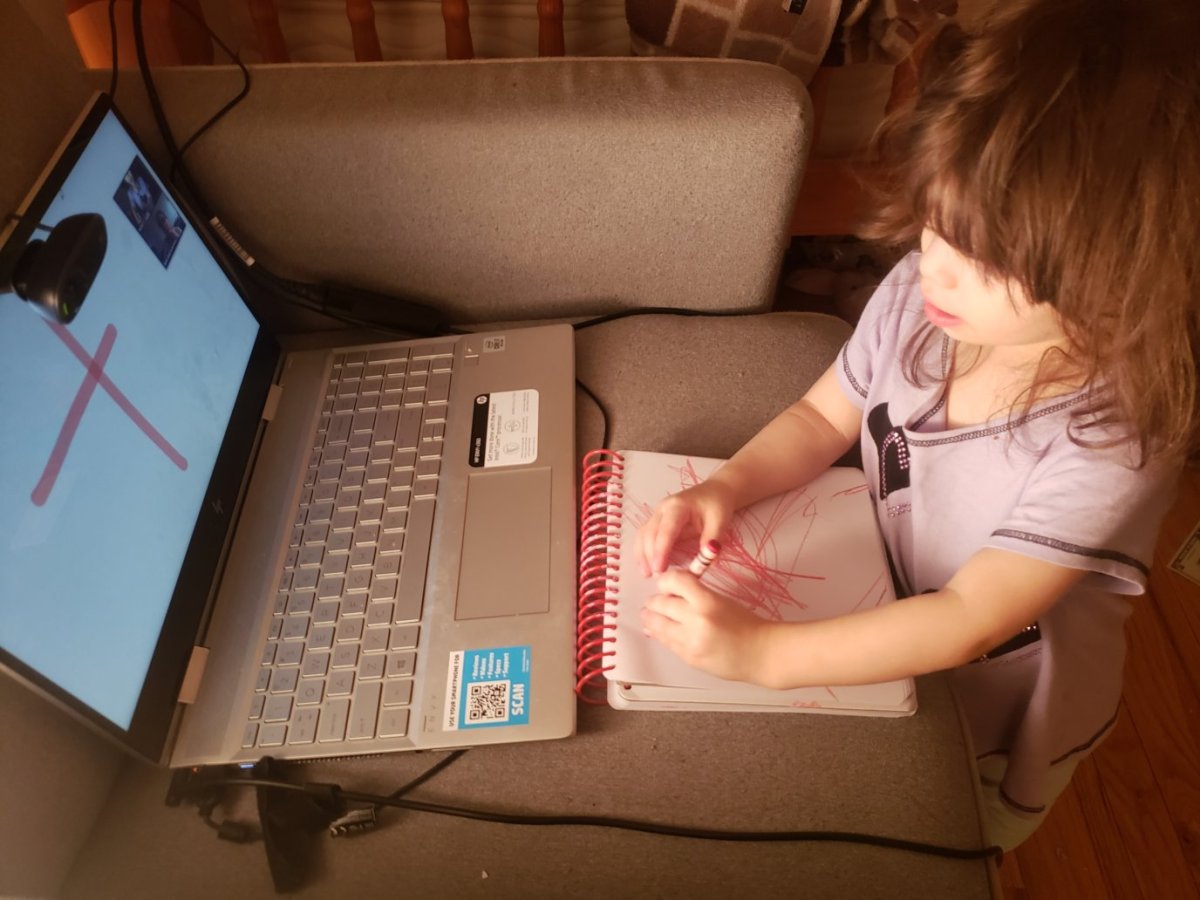

Since then, Sokol has been sitting-in with Aimee and her therapists on daily teletherapy zoom sessions.

Although she is grateful for the service, it’s been a completely different experience — one that she says isn’t quite effective as an in-person therapy session.

“Some parents are loving it, but I’m not loving it. I think they’re better for older kids, but for kids like mine, it’s not helping and my daughter is hitting me a lot — this is different,” Sokol said. “It could be months of this or a year, and I’ve considered opting out, but I’m not going to do that to my daughter with no feedback from her therapist of what not to do.”

According to Dr. Karen Dela Santa-Pura, an occupational therapist who began working with Aimee last summer, the teletherapy sessions are effective, depending on the child.

“For other kids, I see that in another light, now that the parents are becoming their therapist, it’s good in that sense because they’re on the same page as I am, and know what we’re working on and can carry it over at home,” Santa-Pura said.

However, for Aimee, the transition from in-home therapy sessions with Santa-Pura to viewing her through a computer screen for 30 minutes twice a week has become difficult. Aimee’s attention span and willingness to perform sensory activities has decreased, Santa-Pura said.

“She doesn’t want to sit in front of the computer and she doesn’t want to do therapy,” Santa-Pura said. “It’s a different dynamic when mom is trying to do it, it might be a little harder for them to understand it’s not normal.”

To help Sokol prepare for a teletherapy session, Santa-Pura sends background information and other things for her to read.

“I admire them so much and am so blessed and grateful they have entered our lives,” Sokol said. “I cannot stress this enough because it’s NOT their fault in any capacity that we had to move to tele.”

Like all mother’s, Sokol wants society to stop judging other parents, and other kids, showing a little more kindness to special needs kids who are lost and scared during this time.

“I hope one day, quite soon, Aimee and the other city EI and SPSE kids can safely reunite with the therapists they love so much—in person— because, at least, in Aimee’s case, they were — and still are — her bridge to leading a life with a bit more ease. Let’s see what happens,” Sokol said.

This story first appeared on qns.com.