On Jan. 27, a federal court ruled that New York City’s Department of Education violated the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by routinely denying students with diabetes access to field trips and bus transportation, a matter that stemmed from a 2018 class-action lawsuit where parents of students with Type 1 diabetes alleged the DOE systemically failed to provide basic and appropriate care for their children.

Spuyten Duyvil resident Jennifer Fox, whose fifth-grade daughter, identified as I.F., is one of three defendants represented in the case, was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 2013. Fox began noticing shortfalls in the city’s education and day care system’s ability to accommodate her daughter’s health condition when she had been denied by a few city day cares at around two years old.

Section 504 of The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 requires public schools to offer accommodations for eligible students with disabilities, which parents say — and the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York ruled — had been systemically unmet by the DOE. Incidents such as I.F. being denied enrollment at day cares across the city and being singled out or “othered” for blood testing at inconsistent locations as early as Pre-K would define the systemic hurdles that I.F. and similar students with diabetes faced with the city’s lack of accommodations.

“When I realized how hard it was to find accommodation in the day cares system, I saw it early on,” Fox told to the Bronx Times. “And in a lot of cases, the (DOE) putting the school’s staffing concerns and inconveniences over the needs of the child.”

During the 2017-2018 school year, I.F. was denied transportation for the entire first month of school because of delays in assigning a transportation paraprofessional, and when she was eventually assigned one, the paraprofessional was frequently absent. In fact, I.F. experienced a “high turnover” in paraprofessionals, including the resignation of one in December 2018, a replacement paraprofessional who resigned in January 2019, and a third paraprofessional for that school year that was not secured until late-February 2019.

The DOE admitted in court that they had not met the needs of students like I.F who travel from the Bronx to the Lower East Side of Manhattan for schooling, and spend approximately three hours on the bus each day. Those unmet accommodations led to I.F.’s father transporting her to school, a luxury that Fox says, would otherwise burden families who lack an adequate safety net of dual parenting, job flexibility or sizable income.

“We were able to kind of deal with it, but one hundred percent if we didn’t have that privilege, there’s no way she could have gotten to school without (one of the parents) losing their job,” Fox said. “And you hear or see stories of a high percentage of low-income, kids of color who have higher levels of health complications and barriers that compound things for their families, and that’s who we are fighting for.”

The DOE contracts with at least 39 companies to transport approximately 145,000 students to and from school. During the 2018-2019 school year, approximately 272 DOE students with diabetes received bus transportation. However, of those students, 170 were assigned to “specialized” door-to-door buses and 102 were assigned to “general” bus-stop-to-school buses.

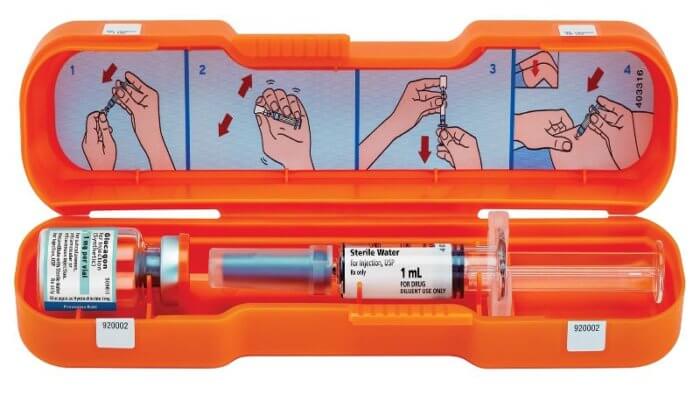

General buses are staffed with a bus driver, while specialized buses are typically staffed with a bus driver and a bus attendant. However, the court found that bus drivers nor bus attendants on specialized buses were trained to administer glucagon, a lifesaving emergency medicine, similar to an epi-pen, that is used to treat severe hypoglycemia.

When untreated and severe enough, hypoglycemia can cause loss of consciousness, seizure, a coma and even death, but DOE officials argued that calling 911 was sufficient to ensure the safety of these students.

“Most trips to and from school are typically of short duration in relation to the school day itself … any sudden emergency can reasonably be accommodated by calling 911 for emergency medical assistance,” an except from the DOE’s statement reads.

However, Dr. Henry Rodriguez, a pediatric endocrinologist with 25 years of experience, rebuked the DOE’s claims, stating that the wait for medical assistance compromised timely safety of students in his testimony.

“Contrary to the NYC school system’s claim that calling 911 is a sufficient and safe practice to assist a student with diabetes experiencing severe hypoglycemia or a diabetes emergency on a school bus, the federal court agreed with the students’ families and the ADA that an adult trained in how to respond to a diabetes emergency, including glucagon administration, should be required,” Rodriguez said to the Bronx Times. “This ruling is a huge victory for NYC public school students with diabetes and helps to ensure that these students will be safe at school and treated fairly.”

As a result, the court has ordered the DOE to train all bus drivers and bus attendants in the administration of glucagon, to ensure that every bus has a trained adult capable of responding in an emergency, and may safely and consistently ride the bus. In some cases, Fox and other parents with disabilities felt pressured to attend field trips to provide necessary diabetes-related care and avoid their children’s field trips being canceled.

“Our family couldn’t be more elated by this historic victory! It is a new dawn for not only our son, but for the care of all children with diabetes in New York City public schools,” said Yelena Ferrer, the parent of a second plaintiff, named M.F. in the court filing.

Many students with diabetes require assistance with diabetes tasks to attend field trips, but the DOE relies on “unreliable contract nurses,” advocates say, to fulfill field trip requests. From September 2016 through March 2020, requests for trip nurses went unfilled 23.2% of the time, which the city admitted it was likely an undercount, according to the court documents.

To rectify these shortfalls, the court is ordering the city to determine how many trip nurses are necessary to meet unmet needs of students with diabetes and hire a sufficient number of nurses to serve as a “float pool” to ensure that students can attend all trips.

The DOE asserts that they have taken steps to provide and require all bus drivers and bus attendants to receive basic diabetes care training and inform bus drivers and bus attendants which specific students on the bus have diabetes.

This is not the first legal defeat regarding accessibility handed down to the DOE, who lost a case when a middle school teacher Dayniah Manderson, who lives with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), alleged the DOE failed to build her an accessible bathroom for the 12 years she worked at Mott Hall in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Bronx middle school teacher wins suit against DOE for ADA accommodations

Reach Robbie Sequeira at rsequeira@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4599. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes.