BY GERALD BUSBY | Growing up in Tyler, Texas, I never missed a service at the First Baptist Church. I especially liked Sunday School, which began at 9am, with kids my age gathering to sing gospel songs from a small spiral-bound hymnal called “Youth Sings,” immediately followed by prayers of face-wrenching sincerity in Jesus’ name. I was usually the pianist and was often reminded by the person leading the singing not to get “too fancy,” but just play the chords as written. Connie, a girl in the class, told me that when my playing got too “show-offy,” she lost her place and couldn’t sing.

We broke up into small groups for Bible study, boys and girls in separate rooms. I found myself in the group with a hot thug named Tommy Rudd, who bullied me at school. My Sunday School teacher, Mr. Blake, was in his 20s, married, and wore two-toned white and tan wing-tipped shoes. He was a teller at the People’s National Bank, and I had a major crush on him. I even wrote him an anonymous note asking him to meet me behind the Dairy Queen one Thursday night after choir practice. I sat for hours in my car, parked a short distance away. I was frightened and sexually stimulated to think that he might actually show up. At church, Mr. Blake made me afraid when he talked about the wrath of God and the certainty of punishment for sinners. Years later, I recalled those fears as I sat in the AIDS ward at St. Vincent’s Hospital next to the bed of my dying partner, Sam Byers.

My life with Sam lasted 16 wonderful years, beginning in 1977 when we met at the Gold Coast, a gay bar in downtown Chicago. I was acting in a film called “A Wedding,” directed by Robert Altman. Shooting took place in an Episcopal church in Oak Park and at a crumbling mansion on Lake Michigan just south of the US Naval Training Base near Waukegan. On the set Monday through Saturday, I was Rev. David Ruteledge, a Southern Baptist preacher; and at the Gold Coast on Saturday nights, Gerald Busby, a horny gay man on the prowl. I was attracted to Dennis Christopher, another actor in the cast — but when I tried to initiate a friendship, he softly said, “I don’t think we’re supposed to like each other,” referring to our characters in the film. This was my first time acting in a movie, and I didn’t get what “staying in character” meant until Dennis spoke these words to me.

Sam, on the other hand, fell for me as much as I fell for him, and being in his arms made me feel like I was finally home. He was 25 — 15 years my junior, and that pushed a big button for his father, just eight years older than I. Sam’s parents eyed me with suspicion and distrust. On their first night in New York, Sam and I stayed with friends and gave our apartment at the Chelsea Hotel to his mom and dad. We forgot to hide our sex toys, which were kept in the top drawer of the table next to our bed. They, of course, snooped, and were shocked and offended to see a pink 10-inch dildo. They knew then for certain that I was an evil influence on their son. As they righteously harangued Sam and me, I thought of how different my parents had been when they discovered a copy of “One,” a gay publication in the ’50s, under my bed. Mother told me it was dangerous to put paper under my bed because it might catch fire — “What if somebody dropped a match, and you know that mice and roaches are attracted to paper.” I never heard either of my parents use the word “sex,” nor did I ever hear them call each other by their first names. They were always “Daddy” and “Mother,” even to each other.

They were born in the last decade of the 19th century in Lueders, Texas, way out west. My mother’s nine sisters were tough, loud harridans, and all of them lived into their 90s. I liked best Aunt Zada, my lesbian cousin Ruth’s mother, and Aunt Meta, the one nearest my mother’s age. Meta was just four-and-a-half feet tall; her husband, Frank, was almost seven feet tall and wore overalls.

As a 10-year-old gay boy, I loved to watch Aunt Meta and Uncle Frank doing routine things around their house. It seemed so primitive yet so intensely alive. Aunt Meta would say to Uncle Frank, “Get me a catfish,” and he would grab a large metal hook from his tool shed and wade into the shallow part of the nearby Brazos River to a large rock in the middle of the stream. Uncle Frank knew the catfish fed there. He’d stand perfectly still for several minutes, then, like snow falling, let bits of crackers fall from his huge hand into the water. The catfish immediately swarmed around the slowly sinking crumbs, and Uncle Frank would suddenly plunge the steel hook through the body of a 20-pounder. With the fish still on the hook, he would carry it back to the house and nail it by its bottom lip to a wooden post just outside the back door. Aunt Meta would be waiting with a ladder she’d lean against the post once the fish was in place. Wearing an apron over her dress, she would climb the ladder with a butcher knife and a pair of pliers, slit the skin strategically, fasten the pliers to the skin, and jump off the ladder ripping the skin from the fish. Then she would cut it into smaller pieces, bread them, and deep-fry them in hot shortening, in a black iron pot over a wood-burning fire. As we ate, Uncle Frank would say, “This is a good mess of fish.”

Sam’s mother and sister came to see him shortly before he died. A consoling male nurse ushered them to Sam’s bedside in the middle of the quarantined ward where I was already sitting. After a few polite words, the nurse deftly made his way between the rows of beds toward another patient. I thought of Walt Whitman in a field hospital attending hundreds of young casualties of the Civil War, all moaning in terrible pain. Here at St. Vincent’s, the young AIDS patients weren’t moaning. They were anesthetized with morphine dripping into their veins through plastic tubes. They were dying quietly, no less terribly than Whitman’s young soldiers, slipping slowly out of consciousness.

When Sam and I were diagnosed HIV-positive in 1985, my first thought was, “Who infected us, and when?” In the early ’80s, we explored independently the nocturnal fantasies of the S&M scene at the Spike and the Eagle’s Nest. It was possible, I thought, to be temperate in that exotic indulgence, and I chose the cowboy persona, a conceit I brought from Texas and was comfortable with. In my new role as a bottom, I liked bondage, which reminded me of the gift-wrapping I’d done as a child. The Neiman Marcus Christmas catalogue back then provided perfect models of twine, tied tight around a package. At the Spike, I hooked up with a musician who had studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and taught solfège at Hunter College. He was into underwear as well as bondage, and was specific about how I displayed myself wearing the underwear he’d bought me on Orchard Street.

Most of the S&M devotees I knew in the ’80s were painstakingly bourgeois in their appearance and behavior, and they were serious to the point of stultification. There wasn’t much laughing in the leather and cowboy scenes. Yet that very opaqueness ratified the sexual appeal of costumed young men displaying the shibboleths of commitment to the roles they had chosen to play, and with which they identified. The signals of preference were as rigid as those of any religious ritual: keys on a ring worn on the left side meant top; on the right side, bottom. Blue and red handkerchiefs worn left or right also indicated whether you were top or bottom and whether you wanted a penis or a fist. All this formality inspired an intimacy akin to raping (with a fastidious sense of style) a sexy stranger, or being raped by one. When drugs became a component of the routines, the dangers became harder to ignore. Crack was the drug of the moment and its effects instantaneously released all inhibitions. They also made the practical aspects of bondage an ordeal. Who wants to tie slipknots in a cotton clothesline when you’re rapturously stoned?

Finally Sam died, and I despaired. My friend, Craig Lucas, asked the Actors Fund to sponsor me at the Pride Institute in Minneapolis. While I was there, Princess Diana was killed in Paris. We all sat transfixed in front of the TV at the clinic. I fell for one of my roommates, a handsome guy named Gene, who had a deformed foot. My other roommate, Richard, a Native American from a tribe in northern Minnesota, had been busted for selling drugs on his reservation. He told me how the men of his tribe harvested wild rice in marshes. They paddled their canoes alongside the stalks of wild rice, bent them over the edge of the boat, then knocked the grains loose with a cedar stick. When the canoes were full, the men rowed back to shore to dump the wild rice into piles near a blazing fire. They danced on the piles to dislodge any remaining grains from their husks. I wondered, as Richard told me this, if the music they danced to was indigenous to the tribe, or if they grooved on gangster rap blasting from a boom box placed in a canoe turned on its side near the fire. Whichever it was, they boogied on grass.

Within a few weeks after my return to New York, I relapsed and was sent to another rehab, located in the old Billy Rose mansion on 93rd Street, between Madison and Park. Billy Rose was a famous Broadway producer in the ’50s. He was famous for fancy parties attended by celebrities in the very ballroom in which we recovering addicts were now wandering in a daze waiting for the dinner bell. As usual, I got crushes on several men in the group. There was something about the emotional intensity of group therapy, centering on drugs and sex, that always turned me on. I made a few friends playing Mozart sonatas on the rickety little upright piano in the lounge. One fervent Evangelical Christian asked me to play “Softly and Tenderly Jesus Is Calling,” a hymn sung at the end of a gospel service to inspire lost souls to get saved. I knew the song well from my days touring with the evangelist Angel Martinez. It’s a slow, seductive love song with touching harmonies. But I couldn’t go down that path again. After a zealous speech, the Evangelical Christian slipped away to the laundry room where he stole an iron and sold it on the street for drug money — or so he said when he returned the next day. My older sister Juana Mae called me from Dallas and told me in tears that she couldn’t believe I was in such a place. She said she’d pray for me and would send me money once I was back at the Chelsea Hotel. After my 28 days were up at the rehab and I was back home, a Walgreens money order came in the mail with a note from Juana Mae that said, “Jesus loves you and so do we.”

Stanley Bard, the manager of the Chelsea, moved me from the four-room apartment I’d shared with Sam to a studio down the hall. The transfer came with an admonition, and a promise: “Pay your rent on time and behave yourself, and you can stay here the rest of your life.” The room was small and dingy, but it had an energy that infused my music, and everything else I did, especially sex, with a sense of adventure. My taste for danger was receding, and something good, though inexplicable, was taking its place.

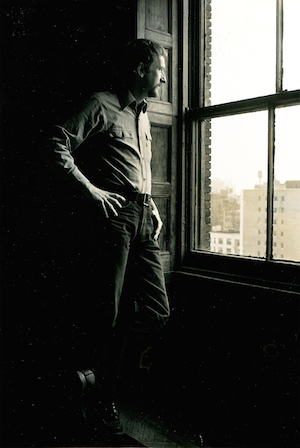

Gerald Busby is a longtime resident of the Chelsea Hotel and protégé of Virgil Thomson. He is best known for his film score for Robert Altman’s “3 Women” and his dance score for Paul Taylor’s “Runes.” With Craig Lucas, Busby is currently writing an opera based on “3 Women.” Busby’s life at the Chelsea Hotel is the topic of “The Man on the Fifth Floor,” a documentary film currently in production.