BY PAUL SCHINDLER | With Americans reeling from a week in which they watched video of two African-American men killed in police shootings that many observers concluded involved wildly disproportionate uses of force and then saw five Dallas police officers gunned down in targeted shootings as they oversaw protests over the earlier killings, New York officials scrambled to emphasize the need for unity and understanding among all communities and between civilians and law enforcement.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, Police Commissioner William Bratton, other city officials, and some elected officials from Manhattan’s East and West Sides all urged empathy for the pain felt among African Americans as well as within the ranks of the NYPD. The mayor and the commissioner specifically addressed questions about police officers’ safety while handling volatile crowd situations, but elected officials currently serving uniformly acknowledged as well the persistence of racial disparities that give rise to incidents like last week’s police shootings in Baton Rouge and a suburb of St. Paul.

The response from officials came against the backdrop of thousands of protesters gathering in Times Square on Thursday — prior to the Dallas shootings — and hundreds more protesting on each succeeding day through the weekend, in locations from Times Square to Grand Central Terminal and Union Square. Thursday’s protest drew the largest crowed — estimated by police at 1,200 — with more than 40 arrested during a Times Square sit-in. Several dozen protesters were arrested at a Saturday protest.

Alton Sterling was shot to death in Baton Rouge after police officers tackled him. Philando Castile was shot to death during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, a St. Paul suburb. The police officers killed in Dallas were Patrick Zamarripa, Lorne Ahrens, Michael Krol, Michael J. Smith, Brent Thompson.

Speaking on WNYC’s “Brian Lehrer Show” on July 8, the morning after the Dallas tragedy, de Blasio said, “An attack on our police is an attack on all of us. It’s fundamentally unacceptable. It undermines, you know, our entire democratic society.” While he and Bratton agreed there was no evidence of any similar attack on police threatened in New York, the mayor announced that for the time being all officers would travel in pairs and that large scale protests would have a “very large” police presence “to really make sure things are very well controlled.”

“This is painful,” de Blasio continued. “And I want to just urge all listeners — whatever you feel politically, recognize that our police officers are hurting today.”

The mayor, however, did not shrink from emphasizing legitimate grievances the African-American community has about repeated episodes in which video evidence has surfaced of black men dying at the hands of police in situations where the use of force has been of questionable legitimacy. “We absolutely have to be able to do both,” he said, when asked whether the nation can mourn and be angry about the deaths in Louisiana and Minnesota as well as in Texas.

The mayor also stood by comments he made several years ago about the warnings he has given his teenage son Dante — whose mother, First Lady Chirlane McCray, is African-American and who sports an attention-grabbing Afro — about being very careful in any dealings with police. Some police critics blasted de Blasio over those comments, saying they unfairly stereotyped the way cops treat black men.

“What I was saying in 2014 — and I have affirmed it since — is just a fact of life in America that we have to grapple with,” the mayor said. “And the events earlier in the week only compounded it.”

Like the mayor, other local elected officials struggled to balance anger at the execution of police in Dallas with continued concern about police killings of black men.

East Side Congressmember Carolyn Maloney, in calling for US Justice Department investigations into the Louisiana and Minnesota killings, said, “In a space of just two days — 48 hours — two African-American men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, lost their lives during separate encounters with police officers. Their names are added to an already too long list of African Americans who have been killed in similar situations.” The following day, responding to the shootings in Dallas, she said, “This vicious and targeted attack on Dallas police officers who were working at an otherwise peaceful protest shocks the conscience and troubles the soul. It is a despicable act.”

Maloney’s West Side colleague, Jerrold Nadler, struck much the same tone, saying, “The tragedies of Alton Sterling or Philando Castile are not isolated, they are the most recent in what is a long list of senseless murders of black men, women, and children whose encounters with the police can only be described as the worst form of injustice and inequality. The additional tragedy of Dallas strikes at the core of all Americans, when those who put their lives on the line to protect, uphold, and defend our rights become targets themselves because of who they are and what they represent.”

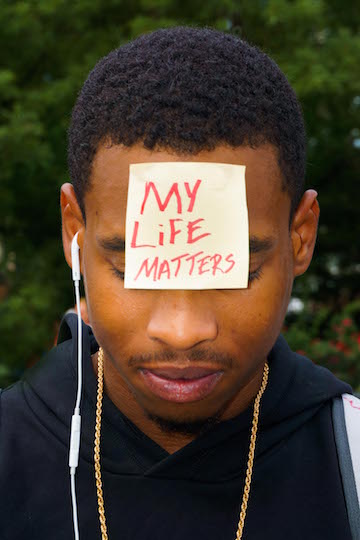

Voicing a balanced response to last week’s events was not without political risks. As some commentators came forward to insist that “blue lives matter” and “all lives matter,” activists aligned with the Black Lives Matter movement complained this response trivializes the injustices the African-American community too often suffers. The difficulty of striking just the right tone may explain why out of more than a dozen East and West Side city councilmembers and state assemblymembers and senators Manhattan Express contacted, only a handful offered comment.

East Side Councilmember Dan Garodnick, in a carefully measured response, said, “Each of these tragic episodes is a grave reminder of the work our nation still has to do to root out violence and racism in society. I ask all New Yorkers to join me in both honoring the sacrifices of men and women in uniform and acknowledging the continued injustices against communities of color across America.”

Referring to all three incidents, East Side Senator Liz Krueger was more specific, saying, “These terrible acts occur at the intersection of many challenging issues, including persistent racism, mass incarceration, gun violence, and criminal justice reform. In response to such violence it is important to heed calls for unity and solidarity. But at the same time we must also seize this moment to move our society toward greater justice and inclusiveness.”

One of the strongest acknowledgments of frustrations within the African-American community came from West Side Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal. Arguing that given the current tensions in the nation, “the job of our men and women in blue becomes more difficult, and they more vulnerable,” she added, “Violence is not the answer, but neither is inaction… We must call out racism in whatever form its ugliness appears. Routine traffic stops do not end in death for white people, and we must all acknowledge this difficult truth. Their lives mattered; black lives matter. We must demand that justice is served.”

Several elected officials emphasized specific steps to help New York move beyond the anger and sadness of last week. Comptroller Scott Stringer — a longtime Upper West Side assemblymember — calling on the city to “emerge from our grief united and with a renewed resolve that recognizes that our differences are our strength and not our downfall,” co-sponsored a Unity Walk organized by State Senator Jesse Hamilton in Brooklyn.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, a former Upper West Side councilmember, saying she was “horrified” by the killings in all three cities, pledged to “reconvene and expand” roundtables she, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, and civil rights attorney Norman Siegel organized last year to strengthen bonds between the police and youth, community leaders, and clergy across the city.

Some African-American leaders were clearly cognizant of the risks of backlash against activism like the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the Dallas killings. The Reverend Al Sharpton, who as head of the National Action Network has led many of the protests nationwide against police shootings involving black men, rejected the notion that Dallas demonstrated that protest is encouraging anti-police violence. Denouncing a New York Post front page that declared, “CIVIL WAR: Four cops killed at anti-police protest,” he told the Daily Beast, “Although I unequivocally denounce what happened in Dallas and have stood with the families in Baton Rouge and Minnesota, by no stretch of the imagination is this a civil war. To say it’s a civil war is to act like all policemen are like the two cops in Louisiana and Minnesota, and that all blacks are like whoever the gunmen were in Dallas.”

Letitia James, the public advocate who is the first African-American woman elected citywide, was blunt in rebutting the view that recent events point to a zero-sum faceoff. “Supporting our police and demanding civil rights for all are not contradictory ideas,” she said.

Not every leader in New York voiced the same confidence — or interest — in bridging the nation’s divide on matters of race and policing.

In a Sunday morning appearance on CBS’ “Face the Nation” that drew widespread attention — and criticism — former Mayor Rudy Giuliani said, “When you say black lives matter, that’s inherently racist… That’s anti-American and it’s racist.”

Giuliani, whose two terms in office were punctuated by a number of divisive battles over police treatment of African Americans, asserted, “If you want to deal with this on the black side, you’ve got to teach your children to be respectful to the police and you’ve got to teach your children that the real danger to them is not the police, the real danger to them 99 out of 100 times, 9,900 out of 10,000 times are other black kids who are going to kill them. That’s the way they’re going to die.”

Pat Lynch, the president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association who has been a frequent critic of Mayor de Blasio’s posture toward the police, said, “Most of the anger directed at police officers over the past few years has been fueled by erroneous information and inflammatory rhetoric put forward by groups and individuals whose agenda has nothing to do with justice. Our elected officials fail us when they prejudge incidents without having all the facts and disparage all law enforcement.”

Commissioner Bratton, Lynch’s boss, was considerably more conciliatory toward communities that question the conduct of police in specific cases. The events of the preceding week, he said at a press conference on July 8, need “to be a clarion call for all of us in this country to take seriously the grievances of many in the minority communities in this country have, as well as the concerns that police have.”

And more strongly than most New York leaders who spoke out last week, Bratton focused attention on the ready availability of guns in America.

We’re a country awash in weapons — 300 million of them,” he said. “And I forget the last count of how many of these AR-15-type long guns are out there, the tens of millions.”