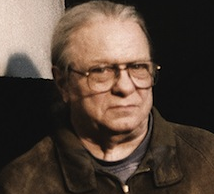

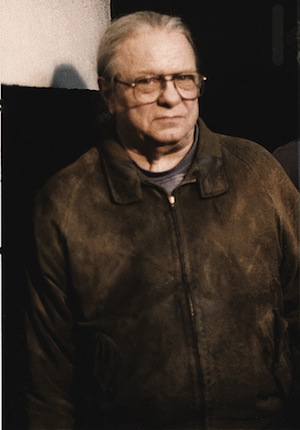

BY JEROME POYNTON | Bill Heine, an influential figure in the 1960s Downtown art and social scene, died on Sept. 15 at Kingston Hospital after a long illness. He was 83.

He was born Bill Mossman, the son of a popular radio show personality. Upon his mother’s divorce, Bill took the name of his second father, Paul Heine. Later in life he used both names.

As a student at the Institute for Contemporary Arts in Washington, D.C., Bill visited Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital with fellow student, Eustace Mullins, secreting in a bottle of wine. Pound proceeded to open and down the bottle immediately without taking a breath of air.

While in D.C., Heine toured as a piano player in a Horton Foote play with Libby Holman.

Moving to New York in the early 1950s Heine visited the San Remo, on the advice of poet Sheri Martinelli, and he became integrated into the thriving New York art scene, rooming with Willem de Kooning and playing drums with Charlie Parker.

Heine socialized with Parker offstage and recalled once entering a drug den with Parker, with Hank Williams entering right behind them. Who knew these two American greats met and shared a drug proclivity?

Heine was acutely aware of how racism impacted the early jazz scene, where police and sailors routinely beat up jazz musicians for sport. In one instance, he remembered drinking Navy men slamming the keyboard cover down on the fingers of a jazz pianist in mid-performance. On another occasion, a black musician stepped between an altercation between New York police and Charles Mingus, protecting Mingus by taking the beating for him. It was a time when jazz greats, such as Billie Holiday, died kicking heroin, under New York Police Department guard.

There were numerous drug busts and the jazz musi- cians were easy targets. Heine recalled a Christmas music review at Rikers Island, where all the inmates renowned in the jazz world played for their fellow inmates.

“Miles Davis declined to participate,” Heine recalled. “He stayed in his cell.”

Often remembered as an artist and musician, Heine’s notoriety in the ’60s was as a practitioner of black magic. He studied the occult with Harry Smith and Lionel Ziprin.

In the ’60s Heine was credited with introducing tie- dye to America. He created his paintings by injecting bundled sheets with dye, using a hypodermic needle, and unfolding them to an array of bright color. In “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” Dylan’s lyric, “The empty-handed painter from your streets/is drawing crazy paintings on your sheets,” is a reference to Bill Heine’s work.

Heine was a member of the Beat Generation with poets Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Janine Pomy Vega, Lee Forester, Clive Matson and many others. Herbert Huncke wrote about Heine in his notebooks, and Irving Rosenthal published this as “Huncke’s Bill India” in his landmark novel “Sheeper”:

“His magic absorbs his spirit—black magic—white magic—Gods and Demons. He practices magic—creat- ing. He reads about the formulas—he knows the forces to command—he calls upon the planets—the moon—the animals—the spirits of wood—metal—stone—earth—of all things—watching for signs—letter combinations—numerical values—good omens—bad omens.”

In 1983 Bill Heine relocated with his companion Anne Spitzer from E. Third St. to Kagyu Thubten Choling, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in Upstate New York. At night, living in separate build- ings, they communicated with each other using flashlights. While living there Heine kicked his heroin habit. The lama allowed him to visit his milk can of beer hidden in the woods off the monastery property.

Heine’s life changed from drug use to a life of vivid spirituality.

Poet Anne Ardolino met Bill Heine on the Lower East Side in the 1960s. Of the neighborhood back then, she recalled, “There were pushcarts on Avenue C with dried donkey penises and pig penises for sale. There were sheep balls hanging from clotheslines in tiny wooden stalls that passed for places of business. There were stools and people sat there and ate meals that had those ingredients.

“Heine was extremely young and thin and had a nose like Karl Malden,” she said. “He was extremely hot, as in sexy,

and he was scary. He was THE person to check with if you wanted to find drugs. He was a criminal and not to be messed with. Period. And yet, as bad as his reputation was — and it was — he never did me harm or caused me grief. Never.”

Heine’s last New York City art show was with tattoo artist Tom Divita, Ardolino and Cochise at the Outlaw Art Museum, curated by Clayton Patterson, in March 1993.

Bill Heine lived in a time when there was extreme crosspollination between art- ists and socialites. The Lower East Side and West Village were the epicenter of this explosion of talent. Rent was not a staged play; it was cheap. Often, the drug world was where people met — some lived but some died young. Those who lived left much evidence of their spirit in today’s film, theater, performance art and music.

A graveside ceremony will take place on Sat., Sept. 29 at 2 p.m. at the cemetery in Woodstock, N.Y.

Letters from art thief Jimmy Porter, written while he was at Downstate Correctional to Bill Heine at Kagyu Thubten Choling monastery, are in pre- production for a staged reading with Penny Arcade, Anne Ardolino and Anne Hanavan in spring 2013.