BY YANNIC RACK | On March 26, when the East Village was rocked by a colossal gas explosion on Second Ave., Fawzy Abdelwahed was in Williamsburg picking up his son from school.

His restaurant, the kosher dairy B&H at 127 Second Ave., although on the same block, was unaffected by the blast and subsequent fire that would destroy three buildings. But the effects are still felt more than three months later.

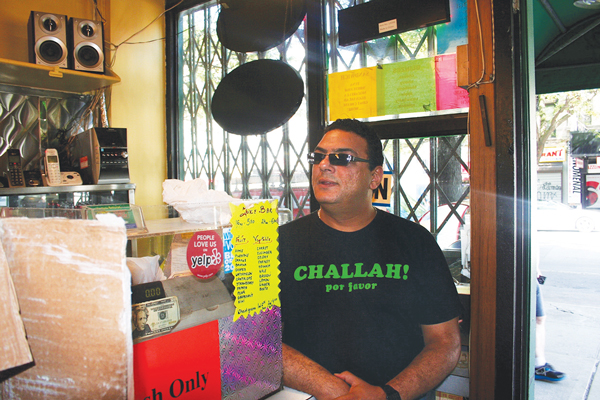

“We haven’t served a cup of coffee since March,” Abdelwahed said, standing in front of his shuttered storefront on Fri., July 10, while contractors were working inside.

The dairy, which has served up borscht and other classic fare since 1938, was closed by the Department of Buildings and Con Edison inspectors who surveyed the buildings in the area in the aftermath of the explosion.

Abdelwahed, an Egyptian native who runs B&H with his wife, Alexandra, has since had to upgrade his fire-suppression system at a cost of $28,000 and replace all of the place’s gas piping. On top of that, his monthly operating costs run up to roughly $30,000.

“On March 26, we worked and everything was fine. After it, my life stopped. I don’t know what we have done wrong, I don’t understand. I really don’t understand. We really suffered very much,” Abdelwahed said, as customers stopped by in regular intervals to express support and ask when the restaurant would reopen.

One of them, Erik Lewis, who passed by on his bike with his daughter Zoë, said he used to frequent B&H in the Sixties when he was a taxi driver.

“I love the place. I used to live in the neighborhood and come here all the time,” he said. “I took my mother here once and it was the previous owner, but the same kind of style. The food is delicious, and not too expensive either. I’m bringing my whole family — one at a time.”

With permits from D.O.B. and the Landmarks Preservation Commission now finally in hand, the contractors started work last Mon., July 6. Abdelwahed hopes he will finally be able to open his doors in early August, but stressed that he won’t hold out any longer.

An online fundraiser for the restaurant was organized in April and brought in $25,000, but the money has come and gone. Another one was set up last week by Andy Reynolds, who has been a loyal customer since he moved to the neighborhood in 1993, 10 years before Abdelwahed and his wife took over.

Reynolds has been lending a hand by reaching out to the media and local blogs, as well as liaising with the city agencies involved in the ongoing renovations. The YouCaring campaign, which runs until mid-August, has already raised more than $7,500 in the first week.

“Everything is going as well as it can right now; they’ve got all the permits they need, they got the contractors there,” Reynolds said.

“It’s been a real financial blow. I have faith that they’re going to reopen but he’s out of money. Hence the crowdfunding campaign — which is going to be a drop in the bucket. With all the expenses they have, the money from these campaigns is helpful but it basically evaporates,” he said, adding that B&H didn’t collect any insurance because the building wasn’t directly impacted by the explosion.

After it emerged that apparently illegal tapping of the gas lines had been made in one of the buildings involved in the explosion, the remaining businesses on the block and in the neighborhood were put under the microscope by city inspectors as well as Con Ed.

“One minute Con Ed said, ‘You’re fine, we’ll turn the gas back on next week’, which was like the week after the explosion, and then they turned on the gas for other buildings but they didn’t turn it on for the building where B&H is,” Reynolds said. “And then the guy was telling them they need to do these upgrades, and it got complicated.”

Now that the permits are approved and work is underway, both Abdelwahed and Reynolds are quick to praise the cooperation with city agencies over the past months, especially the Department of Small Business Services.

“Following the East Village explosion, S.B.S. has worked with more than 40 impacted small businesses,” a department spokesperson wrote in an e-mail on Wed., July 15. “S.B.S. has helped these businesses through the recovery process, with insurance matters, accessing documentation to recoup for lost or damages goods, and a number of other services. S.B.S. has been working very closely with B&H to help guide them through the recovery process, and expedite licenses and permits.”

The e-mail also mentioned the Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City, which announced back in April that it had raised $125,000 to assist families affected by the disaster, but not businesses.

However, the Mayor’s Fund did contribute to a separate fund raised over the past several months by the Lower East Side Business Improvement District, the Village Alliance business improvement district and Community Board 3 to assist businesses affected by the explosion. Yet, applications for grants from this fund were not sent out until last week.

“It is truly characteristic of our city to join together in the face of adversity, and to show compassion and love to our fellow New Yorkers when they need it most,” Mayor de Blasio said in a statement in April.

Now, before the restaurant can go back to business as usual, final approval is still needed from the buildings and fire departments, as well as Con Ed and the Department of Health.

The eatery’s staff, some of whom have found part-time work, will all return once the kitchen is up and running again.

“It’s just got a long history in the neighborhood, so people really want this place to make it,” Reynolds said. “If B&H were to disappear from the East Village, it would be like a hole in the block.”

The restaurant has been a local staple since the 1930s, when Second Ave. was known as the Yiddish Broadway and the restaurant attracted its share of actors and actresses.

Its founder, Abie Bergson, opened the dairy with the help of credit from the surrounding restaurant supply stores. The deal was sealed “on a handshake” back then, according to Florence Bergson Goldberg, his daughter, who sent a letter to the mayor urging him to support the restaurant.

Goldberg, who was born in 1941 and now lives in Florida, last week described how she and her older brother grew up in the restaurant.

“It was wonderful, we knew everybody,” she said over the phone, speaking in an unmistakable New York accent. “Everybody was very attentive to us as children. They were like second parents almost; if we had to go some place, somebody would take us across the street or take us over to the movies, different things like that. They would look after us. A lot of them had their businesses in the area.

“To me, it’s like a landmark, it’s the only surviving dairy restaurant in the whole area from that era,” she said. “You know, the smallest one lasted the longest,” she said, adding that they used to dot every other block.

Of course, the most famous of the dairy restaurants was Ratner’s on Delancey St., which closed in 2004.

Goldberg’s father sold B&H in 1969 and it has passed through multiple owners since then. Despite the changes, some customers have been coming since as far back as the Fifties.

Goldberg said her father actually wanted to be an actor, a fact he reflected upon in his unfinished memoirs, of which she possesses the only copy.

“He had a lot of stars come into the store,” she said. “They used to come in and eat and talk, schmooze around.

“He always aspired to be an actor but life didn’t take him there. So this place, when it opened, to him it became his stage. And everybody in the store, whoever worked there and whoever came in, they were all the characters in the play. It was entertainment, and that’s how he described his own business. He was the director and everybody was an actor, and they all played a part in this ongoing play.”

Almost 80 years on, Abdelwahed said he still feels the same way when he stands behind the counter serving up challah French toast and matzo ball soup.

“It feels like a show that runs every day,” he said, one that all involved hope will resume very soon. “Knock on contractor’s ladder,” Reynolds added with a smile.