In March, amNewYork Metro launched an official coronavirus page on its website with a story about Mayor Bill de Blasio encouraging New Yorkers to take additional precautions just days after the first confirmed COVID-19 case was detected in Manhattan.

Over the past nearly 10 months, the staff of amNY.com has published no fewer than 2,160 stories related to the pandemic — documenting everything from the dramatic, unprecedented shutdown of New York City to the overwhelmed hospitals and temporary morgues; the flattening of the curve; the massive economic damage done to our city; the slow, tedious, partial reopening of the city; and the blessed start of the vaccination process.

Not since the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks has a singular issue dominated the city like the pandemic. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 has impacted the city and country to an even greater extent with respect to the massive loss of life (24,790 deaths in New York City as of Dec. 23, nearly 10 times the 9/11 death toll), the crushing blows to the economy, and the way it has impacted and strained all of our lives.

Lives upended

The things we took for granted and enjoyed before the pandemic suddenly became a grave risk to public health.

Actions like gathering together for a party, going out for a meal, or watching a movie on the big screen were suddenly outlawed in early March due to the contagious nature of COVID-19. Capacity limits were dropped in venues that normally hold hundreds or even thousands of people to just tens.

Theaters, cinemas, comedy clubs, restaurants, bars, sports arenas, even houses of worship were kept off limits for months because of COVID-19. Businesses shut their offices and directed employees to work from home; the Zoom call became the new board room.

Any major public event known to draw big crowds — parades, street fairs, festivals, concerts, etc. — was cancelled after the pandemic arrived.

The St. Patrick’s Day Parade, which marched on for more than than 250 years through war, depressions and past pandemics, was stopped in its tracks by COVID-19.

The LGBTQ Pride March, Puerto Rican Day, Columbus Day and other big parades were scrapped and replaced with virtual events. The Fourth of July fireworks shows were spread out over several days and at several secret locations so as to avoid attracting crowds.

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade went on, but spectators weren’t welcome in person; they had to watch it on TV like everyone else.

For much of this year, Times Square — “Crossroads of the World,” constantly buzzing with people and energy — was a shell of itself, sparsely visited and eerily quiet. It’ll be the same this New Year’s Eve; the million spectators that normally pack Times Square to watch the ball drop will be largely absent, and New Yorkers will have to ring in 2021 from the comforts of home.

School buildings were shutdown in March, and all classes were hastily shifted to online instruction — something completely unprecedented in the history of modern education. The city launched a “blended model” that reopened buildings in September, but hundreds of thousands of parents opted to keep their children home with online learning — and then the buildings were closed again in November due to a COVID-19 spike before being reopened for some students three weeks later.

Scenes of agony

The first wave hit New York in March and April, though some reasoned the virus was here long before and went largely undetected. These were some of the grimmest weeks in the city’s history. The mass “pause” on life, as Governor Andrew Cuomo put it, led to massive job losses and business failure. The unemployment rate reached a height of 20% in New York City, at one point.

And that wasn’t nearly the worst of it. Far more tragic costs were paid.

Not long after the first COVID-19 cases were detected in New York, hospital rooms began filling with afflicted patients desperate for breath, and life.

Then the first refrigerated trailers arrived, stationed outside the medical facilities. Normally used for storing and shipping perishable items, these trailers were converted into makeshift morgues — the vast number of COVID-19 victims having overwhelmed the standard hospital morgue. In some places like Bellevue Hospital, there were several of these trailers parked nearby.

Few will ever forget the images of hospital workers, clad head-to-toe in hazmat suits, face shields and N95 respiratory masks, wheeling body after body out of places like Wyckoff Heights Medical Center in Brooklyn — where the first official COVID-19 death in the city was recorded on March 14 — to the makeshift morgues.

These images, combined with the footage of mass COVID-19 victim burials on Hart Island, the city’s potters field, understored the tremendous and very real loss of life in our city.

Death reigned in New York during late March and early April. At one point, the city lost 800 people to COVID-19 in a single day. Elmhurst Hospital in Queens saw 13 COVID-19 deaths in just 24 hours.

Health care workers labored around the clock, risking their own lives in the process, to medicate, intubate and (all too often) comfort dying patients in person, and their families through cellphones. Isolation rules prohibited too many family members of COVID-19 victims from being with their loved ones in their last moments. For a short time, pregnant women were even prohibited from having birth partners present.

The army of doctors, nurses, lab technicians, anesthesiologists, orderlies and other health care staff did their job as the city and state struggled to procure necessary equipment for the battle — masks, PPE, face shields and ventilators. Some of these workers ultimately paid with their lives.

Aid from the federal government was infuriatingly slow. A lack of national leadership from the Trump White House forced New York to compete with other states and countries to secure medical supplies. Some assistance came with the USS Comfort, the naval hospital ship that was briefly stationed in New York in April.

Volunteer medical professionals from other states rushed into New York in its hour of need, answering to a calling higher than anything coming out of Washington, D.C.

Surviving the pandemic

As horrific as the situation was, New York did what it has always done in other dark times — rise up.

That began with the nightly 7 p.m. salute to health care workers as they changed shifts and went home. Across the city, people applauded, cheered and banged pots and pans out their windows, giving these heroes a much-needed morale boost and a little more strength to keep going.

At New York-Presbyterian Queens hospital in Flushing, snippets of the song “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” rang through the hallways every time a COVID patient was discharged, raising a smile for both staff and patients alike.

Cottage industries popped up across the city to produce masks, face shields and PPE for the frontline health care workers. Nonprofits raised millions to feed the hungry and help those financially impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic; the Robin Hood Relief Fund, for instance, raised more than $115 million in an hour through a star-studded May telethon.

Listening to the advice of experts and the orders of elected officials, most New Yorkers masked up, washed their hands often and socially distanced. In early April, the curve began to flatten, as did the slow, yet steady descent of the virus.

Most businesses remained closed until June, when virus levels reached a low-enough point to begin a phased reopening. Because indoor dining remained off-limits, restaurants were given greater flexibility to open outdoor dining space to bring back employees and customers. The city permitted traffic lanes to be taken up in many areas to accommodate seating.

Outdoor dining proved to be a saving grace for many restaurants, though their struggles remain with indoor dining restrictions. After weeks of appeals, the city and state finally allowed restaurants in late September to open indoor dining space but at a maximum capacity of 25%. But that ended in December due to the ongoing increase in COVID-19 cases amid the second wave.

Even so, some businesses were not allowed to reopen this year — such as the amusement parks of Coney Island, which endured a lost summer by the sea. Movie houses, comedy clubs and bars remain off-limits.

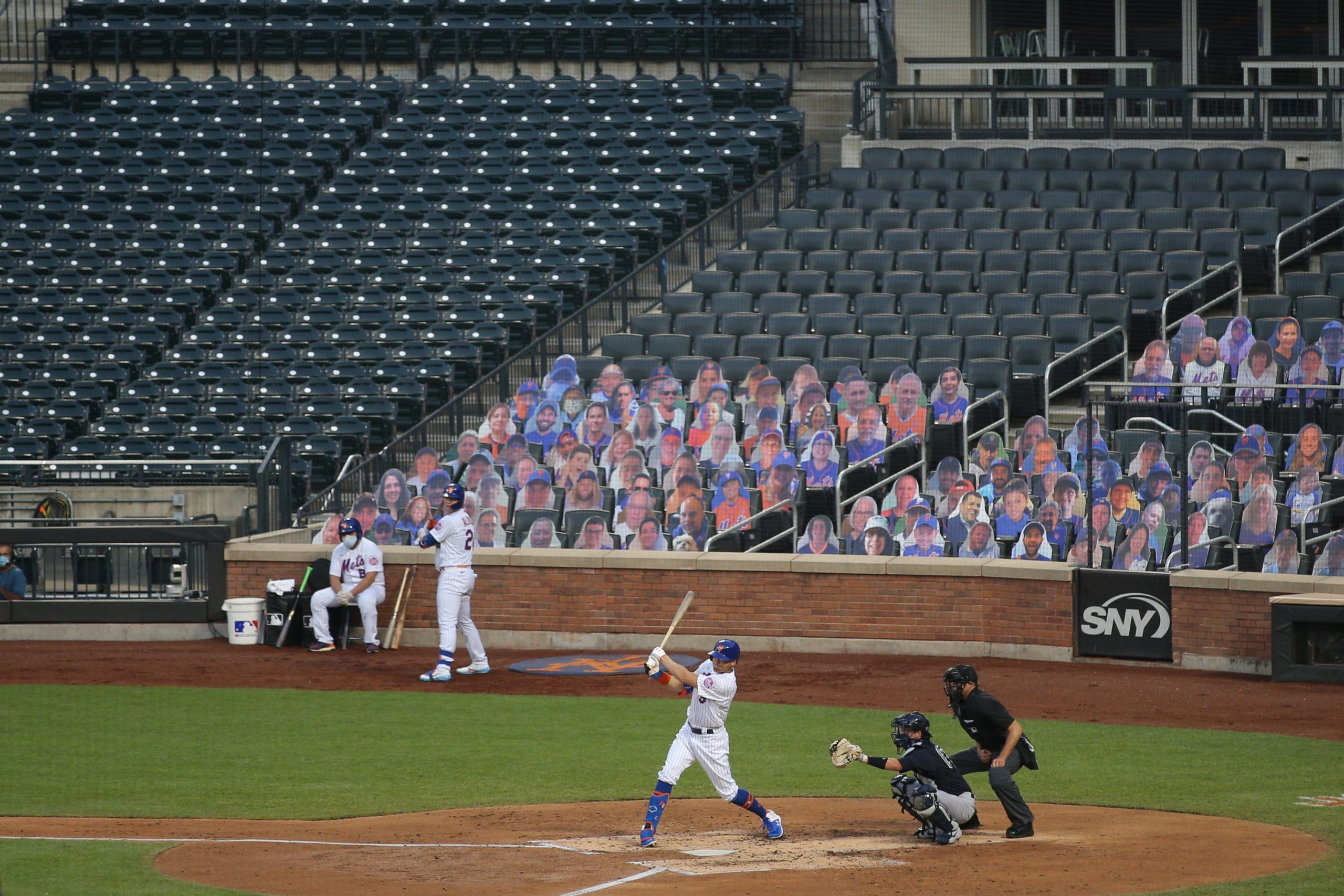

Broadway will remain dark through at least May of 2021. Citi Field and Yankee Stadium had photo cutouts of fans in the stands rather than people during the Mets’ and Yankees’ abbreviated 2020 season; there’s hope at least some fans will be able to return by Opening Day.

Protests and inequality

The pandemic, and the changes we went through as a society, came with two side effects of their own — both of which were very different.

On a lesser scale, there were those who lashed out against social and business restrictions, claiming they amount to a violation of their personal freedom. A few even denied the virus’ severity, even with so many New Yorkers dead, and openly defied mask and social distancing orders. Some businesses completely ignored the regulations and held indoor parties and events — incurring fines from the state and city in the process.

But to a far more dramatic degree, the pandemic exposed the tremendous, underlying and often ignored inequality in New York like never before.

Black and Brown New Yorkers died of COVID-19 at a far higher rate than anyone. Essential workers from communities of color kept the city moving — at great personal risk to themselves, for low wages and less access to quality health care. And when the NYPD became tasked with enforcing mask and social distancing orders on the streets, it led to episodes of police brutality against people of color caught on camera.

The simmering tensions over disparity and injustice finally came to a head following the violent police killing on May 25 of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota — which was recorded on camera and went viral.

Within days, New York City streets were filled with protesters, a number of whom wound up being involved in clashes with police officers. Riots broke out in Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx — looters took advantage of the unrest and pilfered shops. The city and state imposed a curfew to calm things down.

Calls grew in the days and weeks after the protests to “defund the police,” a term that some misinterpreted as a wholesale removal of police funding, rather than shifting some resources away to education and other social improvement programs. The city passed a budget in June that allegedly pared down the NYPD’s budget by a billion dollars, though the actual amount has been disputed.

City government also sought to become more aware of the disparity and looked to acknowledge and address it. De Blasio announced the formation of a Racial Justice and Reconciliation Commission designed to examine and root out institutional racism, in all its forms, in the city.

Cuomo ordered New York City, and all other local governments in the state, to reform their police departments by April 1, 2021, or risk losing state funding. The city and state legislatures outlawed police officers from administering chokeholds against suspects.

Police Commissioner Dermot Shea took the extraordinary step of disbanding the NYPD’s Anti-Crime Units — plain-clothed details that focused on gun crimes and had been involved in many police shootings in recent years — and reassigning the officers to other crime-fighting efforts.

Black Lives Matter murals were painted in each of the five boroughs, including in front of Trump Tower, as a public statement toward advancing equal rights for all, regardless of color.

Just as it will take many more years to address inequality in New York City, it will also take many more months before the city finds itself out of the COVID-19 pandemic. But the end of the health crisis is now drawing nearer, thanks to the arrival of the COVID-19 vaccine.

The vaccines arrive

Queens nurse Sandra Lindsay of Northwell Health became the first New Yorker to receive the FDA-approved Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine at a Dec. 14 ceremony. Pfizer was the first of several pharmaceutical companies developing the shot since the pandemic broke out to receive emergency FDA approval for its use. Moderna received the same approval for its vaccine this month.

Since Dec. 14, more than 50,000 health care workers and nursing home patients have received the first dose of the two-shot inoculation — with millions more New Yorkers waiting to get the vaccine in 2021.

The vaccine arrived as New York continues dealing with the second COVID-19 wave. Unlike the sudden first wave, however, this increase is more gradual than a spike; hospital rooms are not as overburdened as they were in the spring, and advances in medical treatment have dropped the hospitalization stay, intubation and death rates, according to the state Health Department.

Still, as we head into a new year, concerns remain about a post-holiday COVID-19 spike, as well as a mutation in the United Kingdom which has apparently made the virus 70 times more contagious than normal.

COVID-19 will likely dominate much of our coverage in 2021 as it had in 2020, but the tone and scope should be quite different. There’s hope that the vaccine will usher in an extensive healing process for New York, and yet another historic rebirth for the most resilient city on Earth.