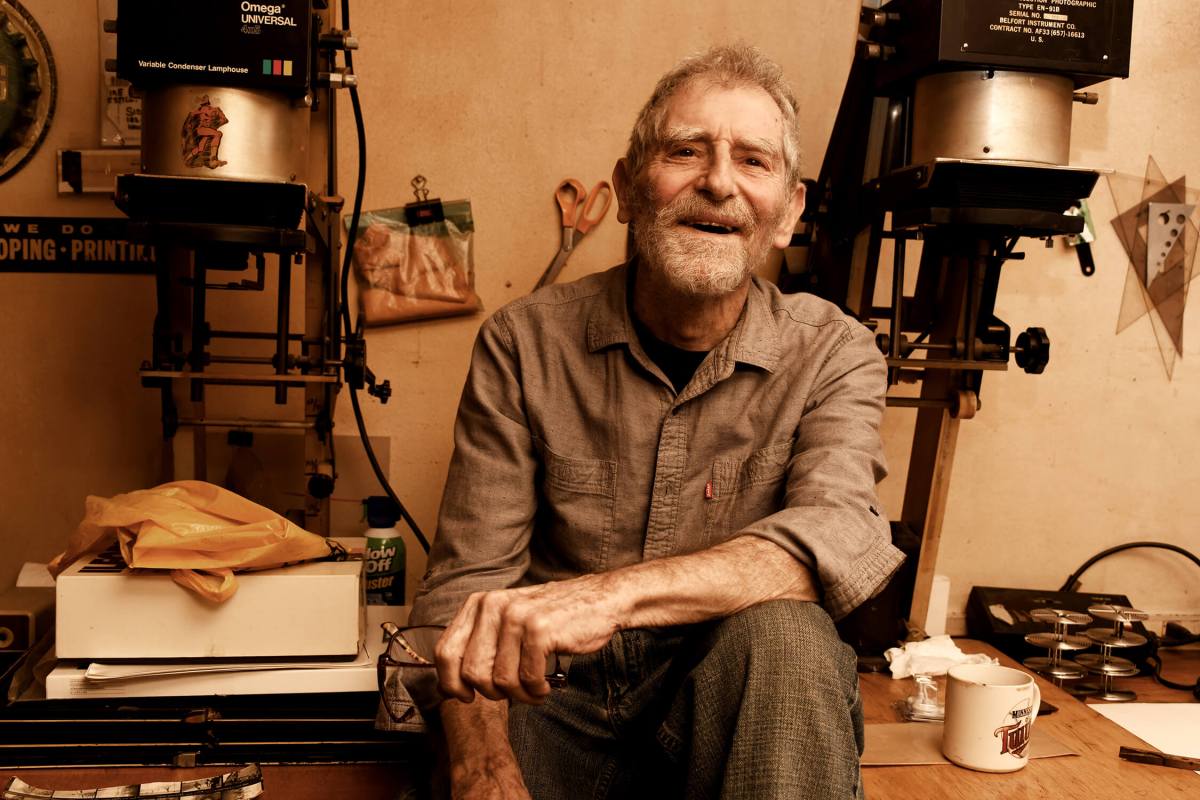

Sid Kaplan, an East Village photographer and master printer, clearly remembers the moment his life in photography began as a youngster in the South Bronx. Now 84, he recounts seeing an image emerge from the developer in a darkroom when he was all of ten years old.

“I was hypnotized!” he recalls. Combined with a precocious interest in the changes that were happening all around him, Kaplan was ready to document his world.

“On Sunday, we had the Daily News and the first thing I wanted to see was the section called, ‘New York’s Changing Scene,'” he recalled. “I was fascinated by the fact that nothing stayed the same in New York.”

He was winning camera club competitions at age 14, but he got some advice from camera store owner Lou Bernstein that he took to heart. “Don’t ever become a commercial photographer,” Bernstein said. “You’ll have to take the pictures that they want you to take, not what you want to do.”

Kaplan spent his high school years in the School of Industrial Art studying the craft but, he says, “they had all these photo classes and I didn’t like any of them! They were teaching us the science of photography.”

More than once he ditched class to document the tearing down of the Third Avenue El, which he shot daily until it was gone. “I got caught skipping once, but my teacher said that he had given me his permission, which he had not.”

While he spent those years shooting with a medium format Rolleicord (“35mm was for amateurs and spies,” he notes), he switched to the smaller format when the “Family of Man“ exhibit changed people’s minds about what was acceptable in the art world. While still capturing the changing world around him, Kaplan had no idea what to do for income.

“I had different jobs — they lasted from two weeks to two days. My first job as a printer ended on the first day when the boss said, ‘get the hell out – you don’t know what you’re doing!’”

Kaplan found work as a photo assistant, with one memorable gig helping out aspiring cheesecake photographers. “Everyone wanted to get a job shooting for Playboy,” he says.

Aspiring shutterbugs would pay for the privilege of shooting a nude model’s form after Sid had set up the studio and taken light meter readings for the various artistes. The famous Weegee, a role model for the young Kaplan, would frequently show up to take pics of the whole scene and

Sid would eventually get to know him, calling him “Uncle Weegee” until the man growled, “Don’t ever call me that again!”

He also worked for Louis Stettner, whom he said “was a bigger influence on me than Robert Frank.” One of Stettner’s steady assignments was creating images to illustrate teen girls’ romance magazines, a far cry from his street photography and a perfect example of Bernstein’s advice.

“Somewhere along the line there was girl,” Kaplan relates. “I got married and found a job as a printer at Modernage, at the time the biggest photo lab in the city, but it wasn’t a nice place and I didn’t last too long.”

It was at his next gig — the Compo photo lab — that he really came into his own as a printer. He started out being “the guy who put the prints in the dryer” and ended up as the go-to man for 30×40 exhibition prints. He still remembers the day that someone handed him the phone and said, “Steichen wants to talk to you.” The next thing he knew the master was giving him instructions on how to print his 8×10 negatives.

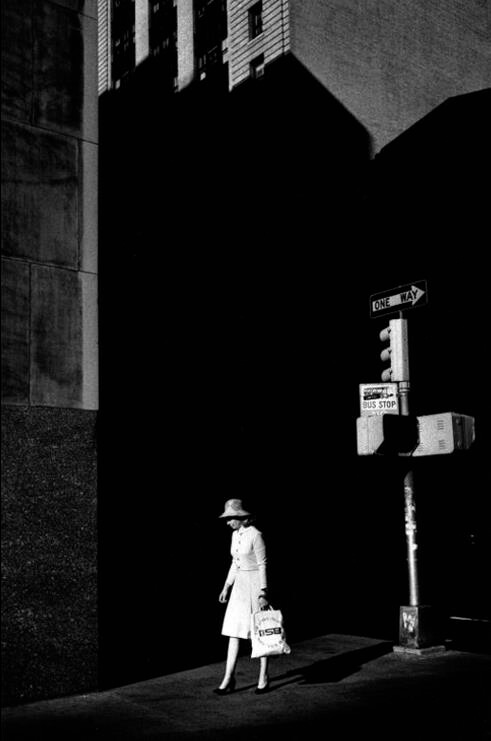

Becoming an expert printer did not keep him from shooting, but his own work got put on the back burner as he went into business for himself. Images by an A-list of photographers including Robert Frank, Louis Faurer, Richard Sandler, Ralph Gibson, Allen Ginsberg, Philippe Halsman, Duane Michaels, W. Eugene Smith, Louis Stettner, and Weegee were brought to life in his darkroom.

Some of those Robert Frank prints, he says, “have sold at auction for a half a million dollars.”

Kaplan has occupied the same compact living space/darkroom in the East Village for over 40 years, still takes his camera with him everywhere and manages just fine without a computer. He’s been teaching at the School for Visual Arts for 51 years and continues to participate in the Highway 12 Road Trip Photography Workshop in Minnesota.

He now concentrates much of his energy on documenting Jewish life on the Lower East Side and has begun to print negatives of his own that have never been seen. Although he’s had the occasional show of his images and a couple of catalogs have been printed in limited editions, he remains largely unknown, possibly due to his own modesty.

“He’s a very humble man,” opines noted photographer and long-time friend Richard Sandler. “He’s equal or better than 99% of who’s out there — one of the best street photographers I’ve ever met. I hold him in the highest regard.”

Deborah Bell, his gallerist in New York, agrees that “he is very modest,” but notes that “his contribution to the history of photography is taken very seriously. He’s part of the long standing tradition that goes from Walker Evans to Robert Frank.”

Randy Gue, the curator in charge of Kaplan’s archive that is now owned by Emory University, states that “Sid’s photographs represent a remarkable collection that documents what he calls “vanishing New York.” Sid’s work rivals Eugene Atget’s photos of “old” Paris. Sid’s addiction to photographing the city, like Atget’s, created a unique visual record of urban change and life in the city.”

Kaplan wouldn’t mind seeing a major retrospective or a book devoted to his photography, but it’s not necessarily essential. “I’d love to see the work out there,” he admits, “but if not – it’s still a great hobby.”

There’s no website or Instagram, but you can connect with Kaplan at facebook.com/SidKaplanPhoto.

Read more: DREAM Charter School Expands Campus in Bronx