Exhibit curator and former Mossad agent Avner Avraham at the entrance of Operation Finale, which gives visitors a brief history of Eichmann and his role in the Nazi Party and the Holocaust.

BY JACKSON CHEN

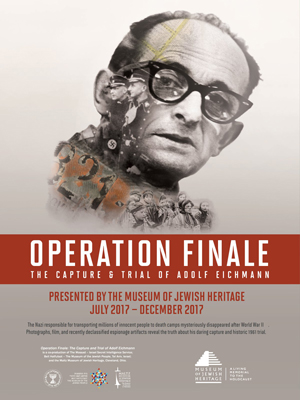

Follow the thrilling capture of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi behind the death of millions of Jews, in the new exhibit at the Museum of Jewish Heritage that opened July 16.

The exhibit, “Operation Finale: The Capture and Trial of Adolf Eichmann,” propels visitors in with a brief history of the Nazi Party, the Holocaust, and Eichmann’s instrumental role in both. Eichmann, who was unsuccessful in high school and failed as a salesman, eventually joined the Nazi Party and quickly rose in the ranks thanks to his efficient plans for the genocide of the Jewish people.

As the Nazi Party crumbled after WWII, Eichmann was able to find refuge in Argentina under the pseudonym “Ricardo Klement” escaping prosecution in the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war crimes.

The exhibition “Operation Finale” explores the gripping capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the major figures responsible for the Holocaust — and one of the last high-ranking Nazis ever to be brought to justice.

Operation Finale guides museumgoers through the infamous Nazi fugitive’s discovery and capture by Mossad, the Israeli national intelligence agency, and the subsequent trial that led to Eichmann’s death by hanging in December 1961. The exhibit features declassified artifacts from Mossad that illustrate a historic moment of justice that unfolded more than 50 years ago.

And it all sparked from a love story, according to Avner Avraham, a former Mossad agent and curator of the exhibit. Avraham explained that they only began actively pursuing Eichmann after a girl named Sylvia began dating Eichmann’s son by chance. After confirming it was Eichmann and his family living in Argentina, Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, requested Mossad pursue the capture of Eichmann.

“You can put [Eichmann] on trial and tell the whole story, not only the story about him,” Avraham said of the importance of the capture and prosecution of a prime architect of the Holocaust by Israelis, rather than the Allies. “The trial was a turning point in Israel because Holocaust survivors didn’t talk about it.”

From the very first reconnaissance photos of Eichmann on a 35-mm film camera to a replica of the leather gloves that were used to kidnap the Nazi, visitors are led through the extensive planning and espionage work that went into capturing Eichmann.

A team of Mossad agents used everything from a primitive license plate forger to fake official documents to blend into Argentinian society. Avraham explained that Mossad agents treated language skills as a weapon too, which was crucial in establishing a cover.

And when Mossad was finally able to smuggle Eichmann back to Israel, the people put their lives on pause to hear radio broadcasts of the announcement of his capture and follow the trial.

“The people stop their life when they broadcast the trial,” Avraham said. “People knew if they have lunch, they have to do it before or after, but not during the broadcast.”

Eichmann’s trial before the Jerusalem District Court gave Holocaust survivors a platform to recount the harrowing sights and experiences, which often left them in tears. To recreate the trial, the exhibit immerses guests with three screens showing archival footage of Eichmann projected into a glass box that the Nazi was held in, alongside simultaneous projections of the judges and the survivors.

During the trial, he was described by New Yorker writer Hannah Arendt as the embodiment of the “banality of evil.” Eichmann coldly claimed that he was only following orders, submitting a not-guilty plea, and offering no emotion during the gruesome retellings from survivors.

But if the testimonies of his victims did not move him, they did move the nation, and helped Israelis to come to grips with a singularly traumatic episode of Jewish history.

“Holocaust survivors didn’t want to talk about anything, they didn’t talk with their kids, their second generation,” Avraham said. “That’s why the trial was very important, to tell the stories of Holocaust survivors to the Israelis and other people.”

Operation Finale runs through Dec. 22.