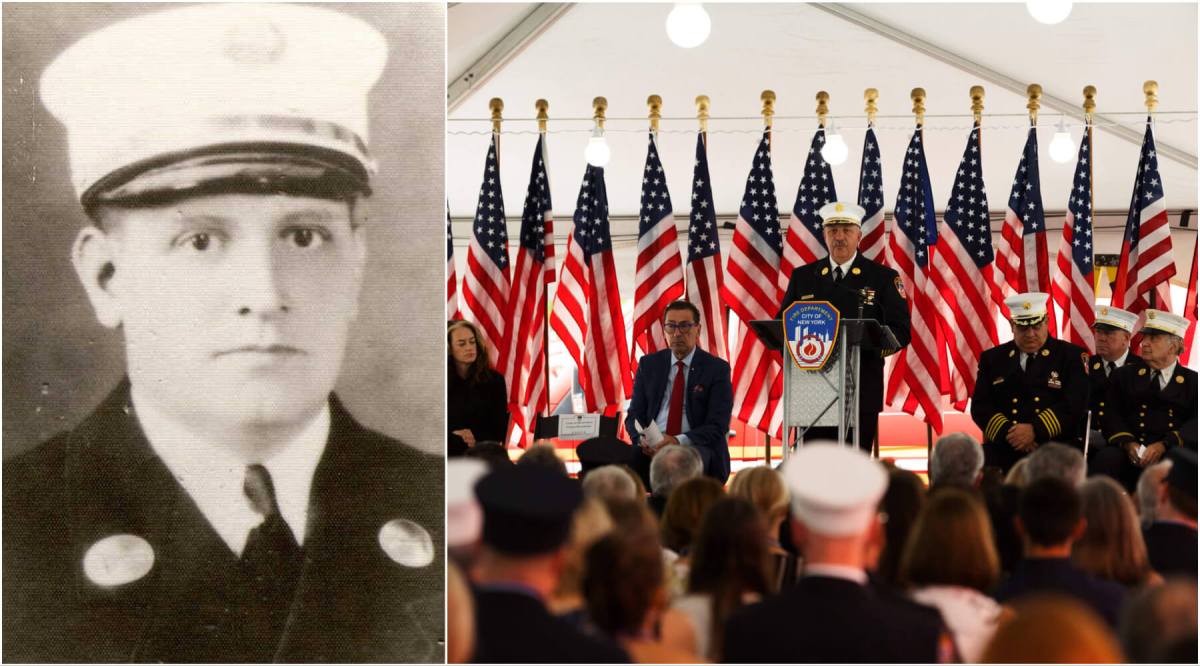

Nearly 80 years after his death, the family of a former FDNY captain is fighting to have his name added to the memorial for firefighters who have died in the line of duty in the department’s Brooklyn headquarters.

Captain Hans Meister, of Engine 292 in Queens, died in his bed in October of 1943, five days after he helped to battle an enormous fire at a Long Island City warehouse.

His death was not considered in the “line of duty” — as he hadn’t died in the fire, or as a direct result of injuries.

For a while, that was the end of the story.

Years later, Meister’s grandchildren began speculating that their family’s patriarch had died from Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome — an often-fatal condition that can be caused by breathing in large amounts of smoke or other toxic substances.

They wondered if his death could be reclassified, and his name added to a long list of firefighters memorialized at the FDNY’s headquarters at MetroTech Center. In the late 90s, an FDNY representative told Hans’ grandson, Richard Meister, that it was unlikely his death could be reclassified — the department hardly ever changes the decisions of past commissioners, and the death had occurred so many years earlier.

“I talked to my brothers and my cousins and all, and we decided, I guess, if that’s what this is all about, they probably missed it in ‘43, they didn’t know what the condition was that my grandfather suffered from,” Richard said. “It is what it is, they don’t change this stuff.”

But then, in 2018, the FDNY did reclassify a death — that of Thomas F. O’Brien, who died from a skull fracture in 1935, likely caused by debris falling on his head during a fire. After many years and a challenge brought by his descendants, the department agreed to add O’Brien’s name to the honor wall in Brooklyn.

The decision inspired Richard to reach back out to the fire department — but, after some back and forth with their legal team, it became clear that the process was going to stretch on. He decided to file an Article 78 petition in Brooklyn Supreme Court, and hired Edward McCarty, the lawyer who had represented the O’Brien family pro-bono.

McCarty — a former state Supreme Court judge and homicide prosecutor — worked together with a team of advisors to compile an investigative report of Hans’ death. The report found Hans had not suffered from any ill health before the fire — and that the department had not investigated his death at the time.

“Although there was no autopsy performed, modern medical knowledge clearly indicates that Captain Meiser died as a result of the fire,” the petition reads.

McCarty asked the court to toss out the former classification of Hans’ death, and instruct the FDNY to designate his death as having been in the line of duty.

Possibly worried about the precedent the change in designation would set, the FDNY moved to have the petition tossed, saying Richard did not have standing to challenge the 1943 decision and that, in any case, the statute of limitations to challenge the decision had passed.

In addition, the department said, no new evidence had been turned up regarding Hans’ death — the FDNY had not conducted a new investigation, and said McCarty’s report was “purely speculative.” Hans’ death certificate states he died from a coronary obstruction and heart disease.

The case bounced back and forth in court for years, being assigned and reassigned to different judges — until it was decided that they would finally appear in court on March 9, 2023.

The fire, and Hans’ death

On October 8, 1943, a fire broke out at the International Diesel Electric Company warehouse on Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City, Queens. The warehouse — which was being used to store engine units and other equipment for the war effort — was quickly engulfed in flames.

Thirty-one companies — including Hans’ Engine 292 — responded to the fire, according to a New York Times article from the following day. At one point, the flames were “several hundred” feet high, and then-mayor Fiorello LaGuardia attempted to order firefighters out of the building.

Within about two hours, the blaze was under control, though it continued to burn into the night. At the time, just seven firefighters were reported injured.

Hans returned home just after midnight, feeling fine and uninjured, according to his family, but developed a persistent cough over the next few days. Five after the fire, after two doctor’s visits, Hans died in his bed at home. The coroner’s report notes that no autopsy was performed, and that the primary cause of death was coronary obstruction.

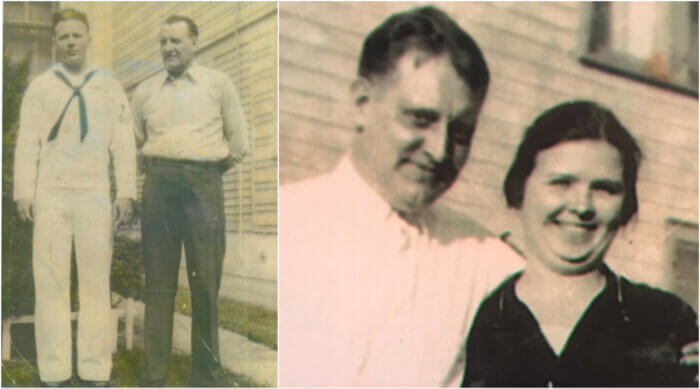

Because his death was not considered “line of duty,” Hans’ wife, Josephine, and six children were not granted any financial compensation by the fire department.

Hans’ death “upended” the family, Richard said, fracturing relationships between them. His father joined the Merchant Marines and headed off to Europe on his 17th birthday, and his younger siblings dropped out of school to work. As they grew older and had families of their own, Hans’ children kept mostly mum about their father’s life and death.

“We didn’t hear much about my grandfather growing up,” Richard said. “We knew that our grandfather was a fireman in New York, that he was a captain, that he was sort of a stern disciplinarian, he was raised by a German immigrant mom and dad. He served in the Navy, went into the fire department, and died when he was about 52 years old.”

It wasn’t until his father was dying in the late 90s that he opened up about Hans, and the effect his death had on the family. Without monetary support, his grandmother eventually lost the house they lived in in St. Albans.

Richard doubts that the fire department actively considered whether or not Hans’ death should be classified as line-of-duty at the time.

“I don’t think they made a decision in 1943,” Richard said. “I think he died five days after the fire, and their rule was you had to die in the fire or in the hospital after being dragged out of the fire, neither of which were the case. They probably all knew he died as a result of that fire, and there’s nothing he could do about it.”

The hearing

Richard, his brother John, and McCarty headed to the courthouse in Brooklyn on March 9 to present their argument to the judge. McCarty argued that the FDNY’s decision not to recognize Hans’ death as line of duty was “arbitrary and capricious.”

The fire department’s arguments closely followed those it made in its first motion to toss the petition — that the statute of limitations had expired, and that his grandchildren do not have standing to bring the petition because they were not harmed by Hans’ death.

A spokesperson for the city’s law department — which is representing the FDNY in the case — said the city stands by the determination made at the time of Hans’ death 80 years ago.

“No concrete evidence has been presented to connect Mr. Meister’s death with the fire he responded to days earlier,” the spokesperson said.

Now, the family — and the FDNY — await the judge’s decision. She could rule in favor of either of them, or could decide the case should go to a hearing. If the decision goes in favor of the Meisters, McCarty said he expected the FDNY to appeal the decision.

The Meister family could appeal too, though Richard said he and his family would have to think on it — those kinds of cases quickly become expensive.

Bill Schillinger, a retired FDNY lieutenant and staff member at the FDNY Retired Members’ Association, an organization independent of the fire department itself, felt the department should recognize Hans’ contribution, especially since the family isn’t seeking any money.

“That’s all changed,” he said, referring to the old line of duty classifications. “I know a lieutenant, a friend of mine, who had a fire and went home and the next day, he was dead. And he got a line of duty funeral.”

Things change all the time, he continued — the fire department’s protocol changes and adapts based on new dangers and experiences. The union lobbied to get more deaths recognized as line of duty when a number of firefighters had heart attacks after fires in the 50s and 60s.

He also referred to the second recognition wall at the Brooklyn FDNY headquarters, for first responders who died from illnesses related to Ground Zero long after the 9/11 attacks. Over the years, more kinds of cancer have been attributed to exposure at Ground Zero, and people who have died from or been diagnosed with those cancers have been able to claim relief money and get recognition.

“There’s probably a whole lot of families out there who have a loved one who was at the FDNY whose death was related to injuries caused by a fire,” Richard said.

If the department agrees to put his grandfather on the wall, he speculates that more will come forward, pushing for their family members to be recognized. FDNY in leadership is in tumult — many higher-ups in the department are angry with the current commissioner, Laura Kavanagh, and have called for her resignation. Early this year, four chiefs filed suit against Kavanagh — the first woman to lead the FDNY — claiming she had unfairly demoted three of them.

“And, that would be a pain in the neck, and, that might further diminish the power of the commissioner and the office,” he said. “And so, they just keep fighting. Fight them until they go away.”