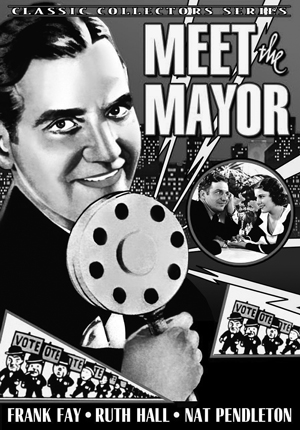

BY TRAV S.D. |

Frank Fay

was copied,

but not liked

“Of all the great vaudevillians, I admired Frank the most.”—James Cagney

Almost all of the great comedians spoke with reverence about Frank Fay (1891-1961). He originated the stand-up comedy style we associate with Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Johnny Carson, Jay Leno and David Letterman: the extremely polished “American Institution” style, an unspoken confidence that says “an army of people made me possible.”

You might call such performers “comic laureates,” almost branches of the U.S. government. As opposed to the more burlesquey Milton Berle-Henny Youngman-Rodney Dangerfield approach, these are not men who take or deliver a pie in the face, cross their eyes or say “take my wife, please.” What they do is tell America the jokes they will repeat around the water cooler at work the next day. While there was no TV in Fay’s heyday, he was the king of the Palace — the flagship NYC theatre of the top vaudeville chain in the nation.

There was much to set Fay apart. Unlike most vaudevillians, Fay was no populist. He cultivated the aloof arrogance of the aristocrat. His trademark was the barbed put-down delivered on the spot with dependable lethalness. That is what audiences prized him for.

He was charming, dashing and impeccably dressed, with a broad handsome Irish face (something like the actor Ralph Fiennes’). He had a very distinctive, swishy style of walking that was almost effeminate — but it was so effective that both Bob Hope and Jack Benny emulated it to their dying day.

He generally finished his act with a sardonic version of “Tea for Two,” wherein he would stop every few bars in order to tear the song apart: “Tea for two, and two for tea.” Then, spoken: “Ain’t that rich! Here’s a guy that has enough tea for two. So he’s going to have tea for two. I notice that he doesn’t say a word about sugar!”

Well, it ain’t exactly “Duck Soup.” But with his wavy hair, straight teeth and twinkling eyes, one gets the feeling that Fay sold his jokes through charm.

Fay was born in San Francisco to vaudevillian parents. He played his first part at age three in a Chicago production of “Quo Vadis?” His first vaudeville act was the team of Dyer and Fay. But it must have been pretty awful, because Fay later downplayed his involvement with it. By 1918, he had established himself as a monologist. By 1919, he played the Palace. “The Great Faysie,” as he styled himself, was appallingly successful on the vaudeville stage. To play the Palace — at all — was the very highest aspiration of most vaudevillians. A select handful ran a week there. In 1925, Fay ran ten weeks. So he might be a little forgiven if it went to his head.

But there is something to the old adage that what lives longest are not words but deeds. Today, Frank Fay lives on in the recorded memory as a notorious SOB and a mean drunk, with nary a kind anecdotal word from anyone who knew him. Milton Berle once said, “Fay’s friends could be counted on the missing arm of a one-armed man.”

An early example of the arrogance that was to overshadow his reputation throughout his career occurred at this early stage. In the incident, which became notorious throughout theatrical circles, Fay let the audience wait several minutes while he struggled to tie his tie in the dressing room. “Let ’em wait!” he apparently snapped at the stage manager, establishing a tradition that would not be revived until rock and roll was invented forty years later.

Fay didn’t go in for slapstick. He used to taunt Bert Lahr by saying, “Well, well, well, what’s the low comedian doing today?” Fay’s bag was verbal wit, and he pulled no punches, offtstage or on. To Berle’s challenge to a battle of wits on one occasion, Fay famously said, “I never attack an unarmed man.”

Apparently, Fay had one of those smirking faces that’s just itching to be smacked. On one occasion, he attempted to humiliate Bert Wheeler by dragging him onto the stage unprepared, and firing off a bunch of unrehearsed lines at him to which he was supposed to attempt rejoinders. Tired of such treatment, Wheeler unnerved him by remaining silent the whole time. When Fay finally cracked and said, “What’s the matter? Why don’t you say something?” Wheeler said, “You call these laughs? I can top these titters without saying a word” and smacked him on the face — to howls from the audience. Some run-ins were far less light-hearted. Milton Berle recalled having watched Fay perform backstage from the wings, which is a real no-no with some performers. Berle heard him say, “Get that little Jew bastard out of the wings,” so (according to him) he grabbed a stage brace and busted open Fay’s nose with it. Lou Clayton also let him have it across the jaw for his smart mouth.

Even when Fay meant to be nice, he was rotten. Introducing Edgar Bergen for his first Palace date, he said: “The next young man never played here before, so let’s be nice to him.” As any performer can tell you, such an introduction is patronizing at best, sabotage at worst.

Bastard or not, Fay’s vaudeville success led to several Broadway shows during the years 1918-33. He even wrote and produced two starring vehicles for himself (a la Ed Wynn): “Frank Fay’s Fables” (1922) and “Tattle Tales” (1933).

Through his friend Oscar Levant, Fay met and married Barbara Stanwyck, then a young chorus girl who’d just gotten her first Broadway show (1927’s “Burlesque”). In 1929, they did a dramatic sketch at the Palace, as “Fay and Stanwyck.” Later that year, they were called to Hollywood, so Frank could star in the film “Show of Shows.”

Some say Fay and Stanwyck’s marriage and their experience in Hollywood later became the basis of a Hollywood movie: “A Star is Born.” The womanizing, alcoholic Fay’s career floundered, while Stanwyck’s flourished for decades. In 1935, the two were divorced — and Fay continued his downward spiral until 1944, when he was chosen to play Elwood P. Dowd in the original Broadway production of “Harvey.”

Fred Allen said, “The last time I saw Frank Fay he was walking down lover’s lane holding his own hand.” He passed away in 1961, a humbler, and, one hopes, a wiser man.

Trav S.D. has been producing the American Vaudeville Theatre since 1995, and periodically trots it out in new incarnations. Stay in the loop at travsd.wordpress.com, and also catch up with him at Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, et al. His books include “No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous” and “Chain of Fools: Silent Comedy and its Legacies from Nickelodeons to YouTube.”