This article was originally published on by THE CITY

A higher waterfront and a lower highway may be on tap for Lower Manhattan.

The city has a new proposal for protecting the Financial District and Seaport from future flooding: extending the eastern edge of Manhattan’s tip by up to 188 feet — while raising the shoreline and possibly taking down the elevated FDR Drive from the Brooklyn Bridge to the Battery.

The city’s Economic Development Corporation plans to reveal a master plan for the FiDi – Seaport resilience project — first proposed by Mayor Bill de Blasio in 2019 as a possible 500-foot extension of Lower Manhattan into the harbor — by the end of the year.

The concept developed from big-picture thinking following Superstorm Sandy about how to protect low-lying parts of the island. In the Financial District, daily high tides will likely flood the area two to three blocks inland by 2100, according to the EDC’s analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency data. By then, coastal storms could surge 18 feet above the current esplanade.

And within that section of Manhattan is a dizzying array of critical infrastructure, both below ground and above — including subway tunnels, office buildings, homes and utilities.

“I can’t imagine anywhere in the United States that is a bigger conundrum in terms of resilience infrastructure,” said Melanie Dupuis, a Pace University environmental studies and science professor who has been keeping an eye on the project. “If they can solve that one they can solve anything. They’ll have to solve it with money and lots of very innovative engineering.”

FDR Drive’s New Deal

The EDC will present updates at public meetings on Wednesday and Thursday. Ahead of that, the EDC recently shared new design ideas with a community advisory group that’s been meeting privately for months to brainstorm about the Seaport-FiDi plan.

At the group’s last meeting on Nov. 4, the agency outlined its latest proposal for the nearly mile-long stretch of waterfront on the east side of Lower Manhattan. According to multiple members of the group and parts of EDC’s presentation shared with THE CITY, the proposal has morphed significantly since the 2019 announcement.

The vision for a landfill extension into the harbor will likely not run 500 feet, but will instead add sections between 90 feet and 188 feet at various points off the current eastern edge of the island’s triangular end.

Obtained by THE CITY

Obtained by THE CITYAlso trimmed is the idea that the new landmass could provide development sites for large, revenue-generating new buildings. The EDC’s current plan includes the possibility of small, one- or two-story new structures, but “no larger residential or office” buildings, a slide from the Nov. 4 presentation reads.

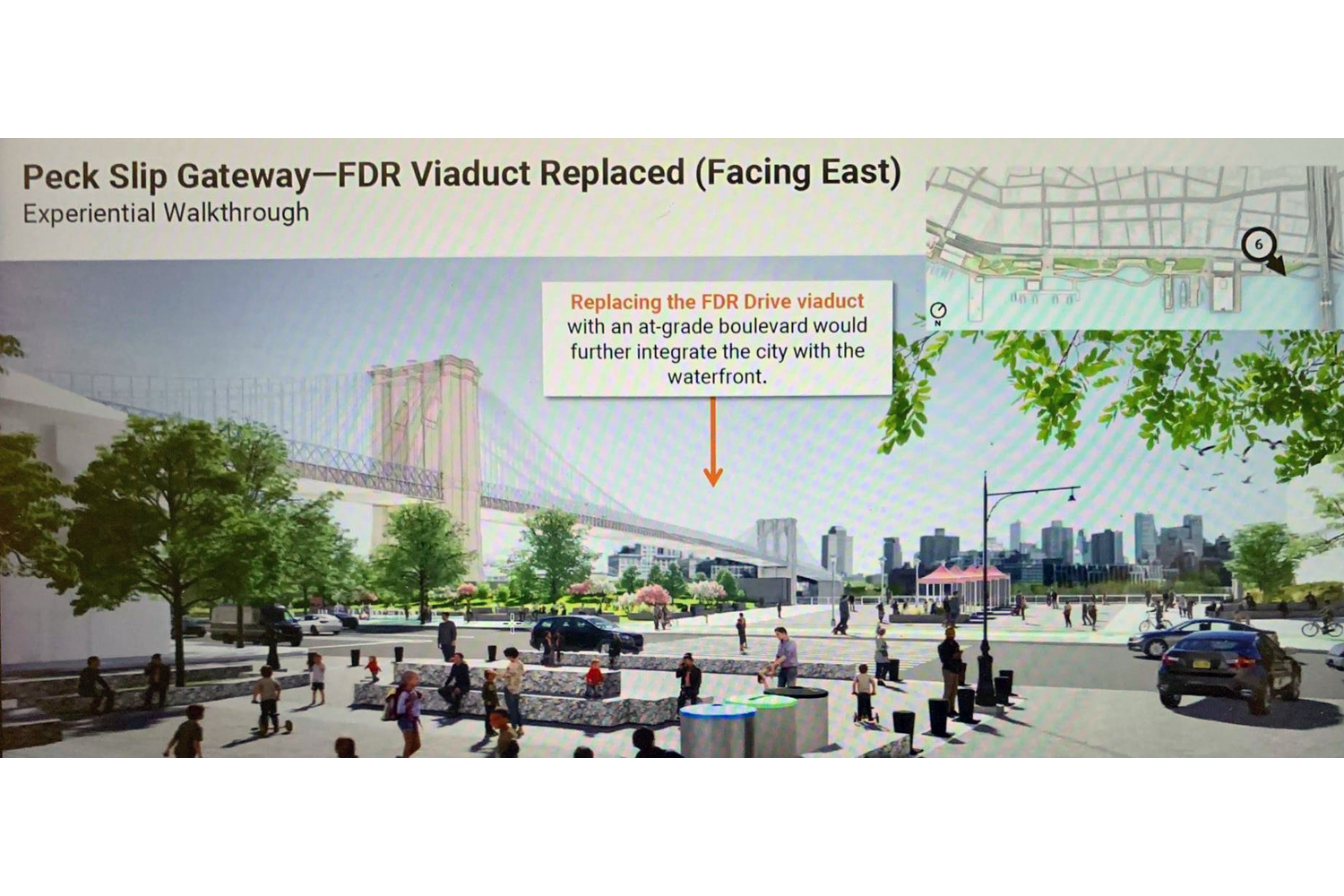

Big change could be coming to the FDR Drive: The EDC is considering removing the current elevated highway that runs from the Brooklyn Bridge down to The Battery and replacing the stretch with a street-level roadway.

Elijah Hutchinson, EDC’s vice president of neighborhood strategies, stressed that the highway’s removal is not definite.

“We’re not proposing to remove the FDR Drive as part of this project, but what we are doing is designing it in a way so that we know if at some future date someone decides that the FDR Drive doesn’t need to be there anymore as a piece of infrastructure, our project still works,” he told THE CITY.

The overall plan is several years and billions of dollars away from becoming reality. The EDC is still talking to relevant parties and needs to secure funding for the project, whether federal or otherwise.

One advisory group member who spoke with THE CITY about the plan on the condition of anonymity called it “wishful thinking right now.”

“They’re looking at anywhere from $5 to $10 billion. They haven’t really priced it all out yet,” he said. “Taking down the FDR at this point would cost a significant amount of money.”

Still, Lower Manhattan residents THE CITY spoke with are taking seriously the EDC’s proposal, developed with input from about 30 community and resiliency advocacy groups, as well as members of local community boards and elected officials.

To Catherine McVay Hughes, a member of the project’s advisory group, removing the elevated highway “is a huge transformative opportunity for the east side.”

“People are very supportive of taking down the FDR. We need to invest in sneakers and bikes,” said McVay Hughes, a Financial District resident for more than 30 years and a former chair of Manhattan’s Community Board 1. “If we’re going to transition away from a fossil fuel environment, it’s important to give people the opportunity to safely walk and bike around.”

A Future of Possibilities

To Amy Chester, managing director of Rebuild By Design, the Seaport-FiDi plan aligns with other conversations and projects around the county that aim “to reconnect neighborhoods that have been separated from their waterfronts, or from the neighborhood next door.”

That includes across the East River from Lower Manhattan, where newly passed federal infrastructure dollars have renewed talk of ripping up the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

“I think with the new conversation about what the future of the BQE is has kind of reignited people’s thinking: What are the possibilities all over the city for the future?” she said.

Aixa Torres, a longtime tenant leader of the Smith Houses on the Lower East Side and a member of the resiliency project advisory group, is more skeptical.

She’s concerned that removing part of the elevated highway would flood the streets around the Smith Houses, located next to the highway just north of the Brooklyn Bridge, with vehicles.

“We’re going to get all that traffic,” she said. “I mean, it’s bad enough we get the fumes from the FDR Drive that’s elevated, and then from the bridge. But then if you bring it down to our level — you know, it’s just crazy.”

Courtesy NYCEDC

Courtesy NYCEDCAccording to state Department of Transportation data, the average amount of traffic on the drive between the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and the Brooklyn Bridge was 50,926 vehicles per day in 2019, the latest year for which data is available.

That’s a lot of wheels. But relative to other sections of the FDR, the traffic total is low.

Just north on the highway, between the Brooklyn Bridge and East Houston Street, average daily traffic was 136,765 vehicles in 2019, DOT data shows. Between East Houston and East 23rd Street, average daily traffic brought 125,622 vehicles in the same year.

Bruce Schaller, a transportation consultant and former deputy commissioner for traffic and planning in the city’s DOT, said the southernmost section of the FDR Drive is “an important link” in the city’s regional travel system — but acknowledged it’s bigger than it needs to be.

“It’s way overbuilt right now,” he said, while adding that it will be affected in the future by the possible changes on the BQE, as well as congestion pricing.

If the city were to bring down the FDR to an at-grade roadway, it would need to figure out how to slow the traffic and allow pedestrians to cross safely to access the waterfront.

Slips Sliding Away

The most recent version of the EDC’s plan is the result of at least two years of work collecting input from New Yorkers about the resilience project and vetting of different possibilities for the narrow strip of waterfront that’s a prime target for more extreme weather caused by climate change.

Much of the Financial District itself is already built on landfill. Water and Pearl streets once ran along the waterfront; the various “slips” — Pike Slip, Rutgers Slip, Peck Slip — denote the names of Colonial-era boat docks.

Today, the low-lying neighborhood is home to some of the densest real estate in the city and waterfront infrastructure: the Staten Island and Governors Island ferry terminals, Lower Manhattan heliport and Piers 11, 15, 16 and 17.

An early iteration of the plan proposes reconstructing the Whitehall Ferry Terminal, creating a new terminal for the Governor’s Island ferry and preserving the Battery Maritime Building without the ferry slips.

The plan may also include the reconstruction of piers 15 and 16. A new helipad and Pier 11 for ferries would be built upon new structures over the water.

The built-out coastal infrastructure would include a series of flood gates and walls, including at the South Street Seaport’s Pier 17. The new design could raise the ground up to 18 feet higher at the highest level.

For McVay Hughes, the work couldn’t come fast enough. She implored local, state and federal leaders to move quickly to finish the design and lock in funding.

“We need to get a shovel in the ground,” she said.

‘Critical for a Resilient NYC’

Multiple locals involved in the community advisory group expressed cautious optimism about the planning process. In particular, those involved seemed relieved and encouraged that the EDC had ditched the idea of including development sites on the possible shoreline extension.

“It’s not Seaport City,” said one downtown resident familiar with the latest proposals, referring to the Bloomberg-era concept for a new neighborhood built onto the East River.

That idea, also floated at the tail end of a mayoral administration, never saw the light of day. Whether the current Seaport-FiDi proposal sinks or swims is dependent on who carries it through beyond the de Blasio administration.

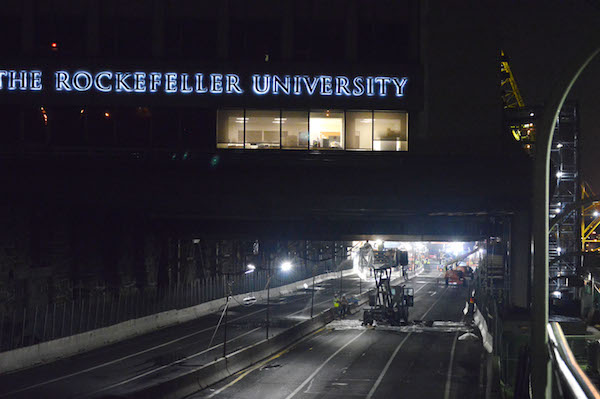

Hiram Alejandro Durán/ THE CITY

Hiram Alejandro Durán/ THE CITY“The history of the waterfront is the history of the mayoral administrations. Every mayor has wanted to make a mark on the waterfront,” Dupuis said. “What kind of mark is [Mayor-elect Eric] Adams going to make?”

In his own waterfront and resiliency plan unveiled in September, Adams pointed to “work[ing] with the State and federal government to fully fund the missing areas of the Lower Manhattan resilience plans” as a priority for administration.

“Securing this area is about a lot more than just these two neighborhoods,” Hutchinson said. “It’s really critical for having a resilient New York as a whole.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.