BY PAUL SCHINDLER | Successful professionals, when asked what inspired their interest and passion for their field of endeavor, will often recall a favorite professor or an older practitioner whose work they admire.

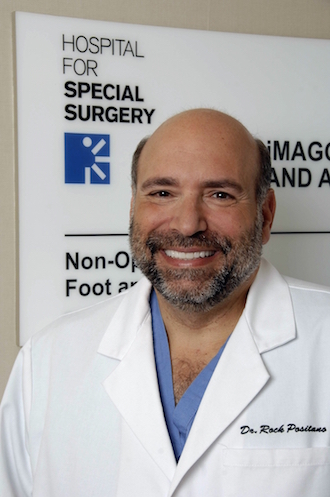

Dr. Rock G. Positano, the director of the Non-Surgical Foot and Ankle Service at the Upper East Side’s Hospital for Special Surgery, looks a bit further back in time when answering the question — to the 15th and 16th centuries.

“My interest in the foot and the ankle came from my study of da Vinci’s anatomical drawings,” he said. “He was amazed that this small device had to carry a human body all their life.”

Explaining that the original Renaissance Man thought about the human body in much the same way he investigated the impact of pulleys and levers in the rudimentary machines he sketched out, Positano said, “I figured da Vinci couldn’t be all wrong.”

The most important insight Positano gained by starting from da Vinci’s perspective is that “feet are the pedestal of the body.” The two most important factors in the average person’s quality of life, the foot specialist believes, are the ability to see and the ability to walk.

And here’s where the “non-surgical” part of Positano’s work comes from: “With foot and ankle surgery, you could do textbook perfect surgery, but there is no guarantee it will work the same way. You don’t want to take a part of the body that is working and change it.”

As with any surgery or non-surgical intervention, Positano explained, “joint preservation is key,” but if surgery creates or exacerbates problems in the foot or the ankle, the impact of those problems can easily migrate “up the chain” to the knees, hips, and lower back. Positano and his colleagues at the Hospital for Special Surgery, he said, are always mindful of the relationship among pathologies in all these parts of the body.

The vast majority of foot and ankle problems, he said, can be successfully and more safely addressed without surgical intervention. That’s a perspective that wins broad agreement among foot care specialists today, but that wasn’t always the case, Positano argued.

“I’d like to think I was a trailblazer,” he said. “Back in the ‘70s, there was a lot of emphasis on what were termed minimally invasive procedures for problems like bunions. Unfortunately, the long term outcome was often not good.”

After earning his bachelor’s degree at NYU, Positano, a Bay Ridge native, received his medical training in the 1980s at NYU’s School of Medicine and the New York College of Podiatric Medicine, before going on for a master’s degree in public health at Yale. It was in New Haven that he focused on “ways to improve foot function without surgical intervention.”

In 1991, he joined the Hospital for Special Surgery, where he found a welcoming climate for advancing his thinking on foot and ankle care. He credits Dr. Thomas P. Sculco, the hospital’s longtime director and a hip replacement specialist, for his receptiveness.

“He understood the importance of proper foot function,” Positano said.

He also singled out the contributions of Dr. Brian Halpern, the first board-certified non-surgical sports medicine physician at the hospital.

Not surprisingly, sports medicine is an important part of the work of the Hospital for Special Surgery, and Positano has served as a consultant to the Mets and the Giants, as well as a sports medicine columnist at the Daily News and expert with the Associated Press. One New York athlete with famously bad knees went to Positano, where he was outfitted with shoe inserts that corrected the problem within a month.

In fact, it is his association with a marquee sports name that likely accounts for how Positano is best known among the general public. Yankee slugger Joe DiMaggio was decades retired when he visited Positano in 1990 complaining of painful bone spurs, which were successfully treated with arch supports. The foot doctor soon found himself part of DiMaggio’s “Bat Pack” of guys the ex-Yankee dined with when he was in New York.

When DiMaggio died at age 84 in 1999, it was Positano who organized the public memorial service held at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and he now he heads up the Joe DiMaggio Sports Medicine Foot and Ankle Center that he founded.

As a New York Times story about the DiMaggio memorial service makes clear, Joltin’ Joe was far from the only high profile Positano client — the list also includes the likes of Rudy Giuliani, Henry Kissinger, and Mort Zuckerman. But the foot specialist emphasized that his practice and research interests connect him with all types of people experiencing problems with their feet.

In collaboration with Harvard Medical School researchers working with the Framingham Foot Study, he has investigated the correlations between problems with bunions, hammer toes, and Achilles tendons and knee and hip pathologies. A peer-reviewed article authored by Positano concluded that nearly 90 percent of youth who suffer from flat arches go on to develop knee and back problems. Dr. Thomas J.A. Lehman, a pediatric rheumatologist colleague of Positano’s at the hospital, often finds that his patients can benefit from examination by a foot care specialist.

With his interest in public health, Positano voiced satisfaction that as much as 70 percent of his practice today is in preventive medicine — not only among athletes, but also business professionals who play sports to alleviate stress.

“They’ll play squash, golf, and of course tennis,” he said. “But professional people today are not so quick to push the button on surgery. They tend to take an active interest in participating in strategies to avoid problems. And nobody wants to be out of work for any length of time.”

It’s the same type of person who will think about preventive care for their children who might be involved in sports.

“Parents are often told there’s nothing that can be done about flat arches,” Positano said. “But then those parents will go around them and come see us.”

On the bet, however, that many more parents won’t think to do that, he added, “We have an active campaign to educate pediatricians about the importance of feet, ankles, knees, hips, and lower backs.”

If feet form the pedestal that influences the health of knees, hips, and the lower back, Positano also points to bigger life and death issues that are involved. Conditions that lead to immobility also contribute to obesity, which in turn can have a severely negative impact on cardiovascular health. Among many positions he holds — including as director of the New York-Presbyterian/ Weill Cornell Medical College’s Foot Center and teaching posts at Weill Cornell, the SUNY Downstate Medical Center, and Brown University — Positano said that one of his “proudest appointments” is in the Cardiothoracic Surgery Department at Weill Cornell.

“I help them to keep patients ambulatory at Cornell,” he explained, a factor that makes a vital contribution to their quality of life — and, often, even survival.

It is sports medicine, above all, that Positano, in talking about his career, seemed to credit for cluing him in to the benefits and satisfaction of that sort of interdisciplinary collaboration.

“One of the beauties of sports medicine practice,” he explained, “is that my colleagues are always looking to integrate other specialties.”

That’s a point of view da Vinci would probably have appreciated.