BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Is Google part of the Meatpacking District? Of course, you could probably just google that to try to find out the answer.

Nevertheless, there was a vigorous discussion about the subject at a community outreach meeting on Mon., Feb. 3, as part of the process of creating a new Meatpacking District business improvement district.

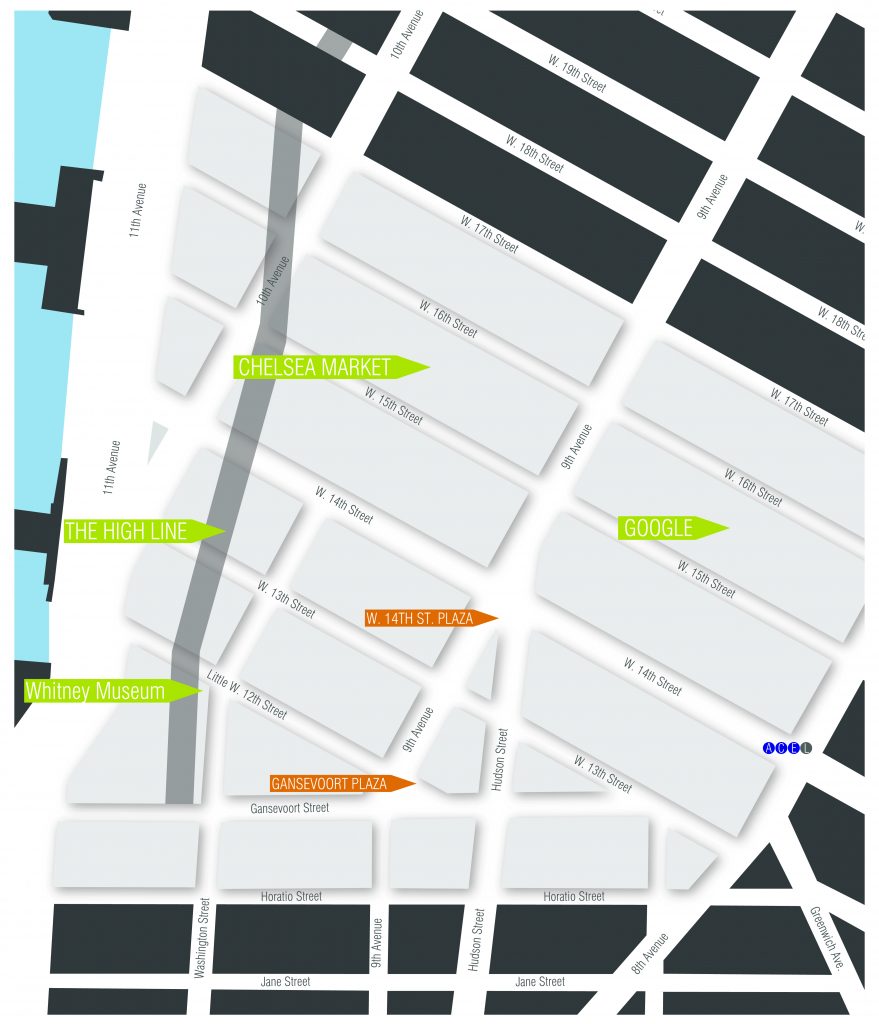

Specifically, the planned BID’s northern boundary isn’t W. 14th St. — which many consider to be the northern limit of the Meatpacking District — but W. 17th St.

Google, which would be one of the heavy hitters in the BID, is located between 15th and 16th Sts. Other major property owners in the planned district, but also north of 14th St., include the Dream and Maritime hotels and Chelsea Market.

The proposed district’s other boundaries are Eighth Ave. on the east, Horatio St. on the south and the West Side Highway on the west.

Lauren Danziger, executive director of the Meatpacking District Improvement Association, and planning adviser Carl Weisbrod gave a presentation of the specific BID-to-be — and about what BIDs, in general, do — before opening up the meeting to questions.

BIDs typically supplement city services by providing things like extra sanitation, public safety, plantings and upkeep of public plazas, programming and marketing for the district.

Weisbrod’s stint advising the startup BID, however, would prove to be short-lived. Just four days later, the HR&A Advisors partner was tapped by Mayor de Blasio to be chairperson of the City Planning Commission.

The audience of about 25 to 30 — including local business owners, residents and community board members — was told that after the BID is formed, M.P.I.A. would continue to exist, serving as a local development corporation, or L.D.C., partnered with the BID. Meanwhile, the current Chelsea Improvement Company would be absorbed into M.P.I.A.

Both M.P.I.A., which currently covers the district south of 14th St., and C.I.C., which covers it north of 14th St., could be called voluntary or private BIDs, in that, unlike as with a city-sanctioned BID, the city doesn’t assess all the property owners in these districts a special tax that is then funneled back into these areas. Local businesses currently only voluntarily contribute to these two organizations.

Danziger said the two “pseudo-BIDs” that exist now just can’t keep pace with the needs of the burgeoning district, which in the years to come will see the arrival of the new Whitney Museum on Gansevoort St., the redevelopment of Pier 57 on W. 16th St., plus new developments at 837 and 860 Washington St. and the Prince Lumber site.

“I think it means a long-term, proactive solution to a district that is constantly evolving,” she said. “For the amount of tourism, and the amount of visiting, and as a place where more and more people are headquartering their businesses — we’re only going to get more foot traffic. But we are currently underserviced. We can only do so much on donations.”

Commercial property owners within the new BID’s boundaries would annually be assessed 22 cents per square foot. Residential property owners would be asked to provide a token $1 total per year. The district’s square footage is about 20 percent residential.

Danziger noted that 4,000 information packets about the BID were recently mailed out — one to every address, whether commercial or residential, in the district. Included among the materials was a support form, intended to be returned to M.P.I.A. to help gauge whether the initiative has sufficient backing. For the city to approve a new BID, it’s required that strong support for the effort from all constituents be demonstrated.

The next step will be to create a district plan within the next few months, to lay out, among other things, what services the BID will specifically provide — in this case, basically, the typical ones — its budget and its formal constitution. The point when the application is formally delivered to the city’s Department of Small Business Services is still a ways off, she said. A vote by the City Council would follow down the road.

Danziger said there is “a natural flow” between the several blocks in southern Chelsea and the Meatpacking District. Employees at Google and visitors at the Dream and Maritime all enjoy going down to the Meatpacking District, she said. In other words, the Meatpacking District makes the blocks north of 14th St. attractive for businesses and visitors alike.

However, Benjamin Stark, representing Christopher Reda, owner of several Meatpacking District businesses, said his client objects to including the blocks north of 14th St.

Reda owns the Sugar Factory, a dessert and brunch place that opened in April, The Griffin nightclub and Gansevoort Market, set to open in June, featuring 24 different food stations.

“If you take out the very large properties — Google and Chelsea Market — Chelsea is a residential area,” Stark declared afterward. “We don’t understand why the Meatpacking District is being exported. Extending three blocks northward seems innocent — but my client and other tenants have a vested interest in that intangible quality that is the Meatpacking District.”

For her part, Danziger said she just “doesn’t get” why there is this opposition to include these northern blocks.

The Chelsea section will disproportionately fund the district’s maintenance, she added, since about 55 percent of the assessed square footage is located north of 14th St., while 55 percent of the actual sidewalk and outdoor area — that will need cleaning and other services — is south of 14th St.

“The work is being done in the south, and the northern part is paying for it,” she explained of the dynamic that would exist. “The reality of the numbers is you just don’t have enough if you only take the Meatpacking District.”

According to a source, the opposition to adding the Chelsea blocks is coming solely from one Meatpacking District property owner.

William Floyd, head of external affairs for Google New York, told the meeting the tech giant isn’t interested in the BID as a means to further boost the area as a club zone.

“As a property owner,” he assured, “we’re not in the business of promoting clubs. We’re in the business of promoting business. We have 4,000 employees.”

Speaking afterward, he said, “I don’t understand the north-south thing. The northern part of the BID district is all commercial.”

Google owns its massive, full-square-block building at 111 Eighth Ave., having purchased it for $1.8 billion in 2010. Floyd noted that, with 2.16 million square feet, it’s arguably the city’s second-largest building in terms of square footage, behind only 55 Water St., though 1 World Trade Center, when completed, will be the largest.

Meanwhile, Ritu Chattree, a 61 Jane St. resident, had another pressing concern — namely, that the Meatpacking District is currently a quality-of-life nightmare for residential neighbors. She wanted to ensure that any future BID would represent the needs of residents, particularly regarding issues of traffic mitigation and public safety.

“Have you ever been out there at 1:30 at night? I did a walk-through with Corey Johnson before the election,” she told The Villager after the meeting. “It was like Mardi Gras in a confined space. We have screaming, we have traffic backing up to Bank St. The volume of the noise coming out of the places is incredible. The Gansevoort Hotel is a horrible neighbor. You could have a party on the ground floor of the hotel from all the music from the rooftop club, Plunge.”

However, Danziger told the meeting she feels the interests of businesses and residents are “aligned.”

“M.P.I.A. has a good reputation of being open to conversations,” she said. “We can have more conversations. We can have a meeting.”

Weisbrod noted that he was involved in getting the city’s original BID law passed in 1980. He was also instrumental in the turnaround of Times Square, which benefitted early on from a BID. In short, BIDs don’t push quality-of-life problems into residential areas on their edges, as one might expect could happen. Instead, they have a positive impact on surrounding areas, he said.

“As the core does better, the periphery ends up benefiting,” he explained. Also, he added, a BID is self-enforcing. “There’s a tremendous amount of peer pressure on a BID for businesses to be responsible,” he noted. Posting unarmed BID public safety officers at “obstreperous locations” can help cool them down, he added.

David Gruber, chairperson of Community Board 2, said of his board, “We like the idea of a BID. I think the problem is, down the road, when this group of people [at the BID] is no longer on the scene. What the BID does not only impacts the BID area, but has a longer-range effect…15 years down the line.”

Gruber said the community would like to see more in writing on exactly what the BID will and won’t do.

The BID’s steering committee includes two residents who live within the district, Jim Jasper and Donna Raftery, plus Gruber and Betty Mackintosh, a C.B. 4 member. Several business owners on the steering committee also live in the district.

So, for the record, how far north did the working Meat Market actually extend in its heyday?

“I’m not sure there is a single clear answer,” Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, later told The Villager. “The Gansevoort Market Historic District we proposed [for landmarking], which was adopted by the state and feds — but scaled back by the city — did go to 16th St., including the old Nabisco factories, which are now Chelsea Market. Nabisco was never meatpackers, but it was wholesale food production and shipping. Meatpackers tended to be limited to the north side of 14th St. and below, with some exceptions.

“That said,” Berman added, “I’m not sure any of this really settles the question of where the BID’s boundary should be. Certainly, the Meatpacking District and southwest Chelsea are much different neighborhoods than they used to be.”

For more information on the BID proposal, visit meatpackingbid.org .