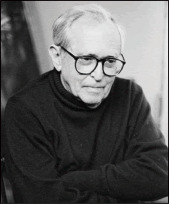

One of the most important American representational artists of the 20th century, longtime Villager Jack Levine died on Nov. 8 after a short illness.

Throughout his long career, Levine remained committed to figurative art, disregarding trends in the art world that did not suit his purposes. This was particularly true in the 1950’s, when abstraction was in ascendance and social content was deemed out of fashion by leading writers and critics.

Levine developed a unique modernist approach, an expressive mode of painting that he used to critique injustice and dishonesty in American society.

Born Jan. 3, 1915, the youngest of eight children of Lithuanian immigrant parents, Levine grew up in Boston’s South End. From 1929, when he was 14 years old, until 1933, he studied painting with Denman Ross in Harvard University’s art department. He was then employed intermittently by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project from 1935 to 1940. Two of his W.P.A. paintings, “Card Game” (1933) and “Brain Trust” (1935), were included in an exhibition, “New Horizons in American Art,” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1936.

The following year, he achieved national recognition when his painting, “The Feast of Pure Reason” (1937), a scathing critique of political and police corruption, entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Another of his paintings, “String Quartet” (1934-’37), was included in the Whitney Museum of American Art Annual for the first time that year. Confirming his rapid rise in the art world, he joined Edith Halpert’s prestigious Downtown Gallery in 1939, at age 24.

Levine’s burgeoning career was interrupted by three and a half years in the Army during World War II. Even so, he gained widespread public notice while serving in the South Atlantic in 1942 when “String Quartet” was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, after being included in its exhibition “Artists for Victory.” The image was later reproduced and displayed in New York City subway cars.

After the war, Levine married artist Ruth Gikow and moved to New York. Gikow died in 1982.

Earlier in the 1940’s, he had begun working on paintings with Old Testament themes, resulting in a series of “Hebrew Kings and Sages” that revealed his more contemplative nature.

At the same time, he continued creating controversy with paintings like “Welcome Home” (1946), a satirical take on a society banquet honoring a returning general, which was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum. Later shown in a State Department exhibition of American art that traveled to Moscow, this painting created an international controversy with its wry look at patriotism and the military hierarchy. Levine, along with several other artists, was subpoenaed to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, though he ultimately did not appear since he was traveling in Spain with his family.

Throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s, Levine continued to create some of his finest works, including what is often regarded as his masterpiece, “Gangster Funeral” (1952-’53), which was acquired by the Whitney Museum. In the early 1960’s, Levine also began creating prints.

In 1979, a comprehensive retrospective of his work that was organized by the Jewish Museum traveled around the country. Levine continued to work steadily through the 1980’s and 1990’s. In 1999, the Brooklyn Museum held a retrospective exhibition of his etchings and lithographs.

Levine received many awards and honors, including a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 1945 and a Fulbright grant to study in Italy in 1950. He became a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Boston, in 1955, and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, in 1973.

Levine once said of himself, “I am primarily concerned with the condition of man. The satirical direction I have chosen is an indication of my disappointment in man, which is the opposite way of saying that I have high expectations for the human race.”

Art historian Milton Brown wrote of Levine, “He is a history painter for our peculiar times, ultimately concerned with the incongruous relationships, ludicrous events and ironies of existence that somehow define our political, social and cultural character.”

Levine is survived by his daughter, Susanna Fisher; his son-in-law, Leonard Fisher; two grandchildren, Rachel and Ari Fisher; a nephew, Robert Fishman; and two nieces, Myra Fishman and Elaine Weiner. A memorial service will be announced at a later date.