By Lincoln Anderson

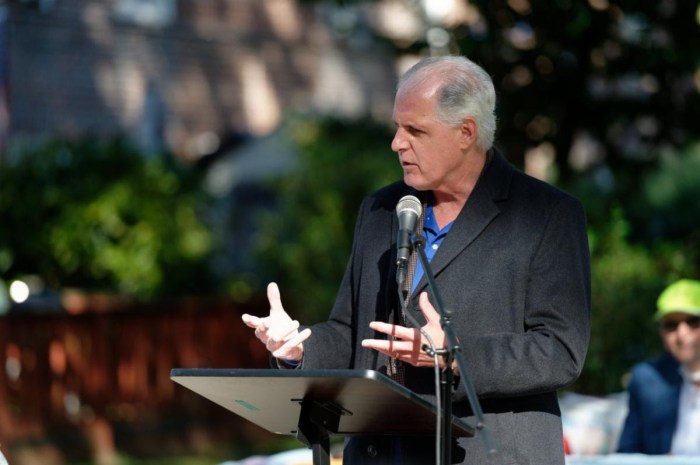

After a sometimes-tumultuous 10 years leading The New School, Bob Kerrey has turned the page and is moving on to the next chapter in his life. That new chapter may include writing a book about American politics. It might also see him head a political institute connected to The New School. And, he hopes, it will see him reacquire his “political voice,” which, he admitted, he had to stifle far more than he liked while university president.

Kerrey — a former Nebraska governor and senator — stepped down as president of the iconic Greenwich Village university at the end of December, and his replacement, David Van Zandt, took over at the start of this month.

Kerrey, 67, sat down with The Villager a few weeks ago for a wide-ranging conversation about his tenure at The New School, his own personal narrative, the state of current politics and what the future might hold for him.

Among the school’s biggest accomplishments under Kerrey is the recent start of construction of its new University Center, on the east side of Fifth Ave. between 13th and 14th Sts. The $361 million project, sporting 16 stories and 365,000 square feet, will have a 620-bed student dormitory in its top half and an auditorium in its bottom.

The building’s design faced much scrutiny from the community. But The New School hasn’t endured anything near the sort of angry backlash New York University has over its N.Y.U. 2031 expansion plans, which call for millions of square feet of new space to be created in the Greenwich Village area.

“We don’t have the ambition that N.Y.U. does,” Kerrey stated. “N.Y.U. is in a very different situation than we are.”

And yet, Kerrey said, in the last five years, The New School may have had the largest increase in full-time faculty of any academic institution in the country. The school now boasts 375 full-time faculty and 1,200 adjuncts. Six years ago, he said, The New School — always known for its graduate programs and continuing-education courses — decided to make undergraduate education its priority.

In many ways, The New School, with its former emphasis on Ph.D. programs, has developed “back-asswards,” the plainspoken Kerrey quipped.

Rebranding its various schools under The New School umbrella also helped create a feeling of a more unified university: Parsons, for example, was redubbed Parsons The New School for Design.

Provost showdown

On academic issues, one of Kerrey’s rockiest moments as New School president was two years ago when he decided to install himself as provost — the university’s chief academic officer — after the previous provost’s departure. The move resulted in a stinging faculty vote of “no confidence” in him. Looking back on his decision, Kerrey said it was a misstep, but that it was beneficial since it ultimately strengthened the Provost’s Office.

“We had a very weak Provost’s Office,” he said. “A weak provost was O.K. 10 years ago. It was not O.K. two years ago — and we’ve changed that.”

As for the overwhelming no-confidence vote and the criticism that he took then, including calls for his departure, Kerrey said, “Some of it was honest — and some of it was dishonest. There were statements made that I was destroying the university.”

In fact, he said, “The New School in Exile wanted to destroy the school.”

He was referring to a students group that was fomenting building takeovers and campus protest. In December 2008, students occupied 65 Fifth Ave. for 32 hours. Another attempt to occupy the university building in April 2009 ended after only a few hours as The New School called in police to make arrests.

“It’s tortured thinking,” Kerrey said of the radical students group. “The language is similar to an anarchist or ultra-radical.”

Kerrey said that during the first standoff, after he left the negotiations at 65 Fifth Ave. and was walking back to his nearby brownstone, student protesters had tried to provoke him. Some had shouted, “War criminal!” at him.

“I know exactly what they wanted,” he said. “They wanted a physical confrontation with me. I’m proud to say, at 65, one leg, I outran the sons of bitches back to my wife.”

A decorated veteran, Kerrey lost part of one leg in combat in Vietnam.

Later that night, a group of students came riding by his house on black bicycles and wearing black clothes, and graffiti was scrawled on the building’s exterior, Kerrey recalled.

“I don’t know what they were thinking,” he said.

But, he shrugged, it wasn’t the first time he’d experienced intimidation; he noted, for example, he received death threats when, as a politician, he had voted for tax hikes and gun control.

And he was simply used to opposition as a given in his former career. He noted that when he was in politics in Nebraska for 16 years, he always had a “30 percent disapproval rate,” since not everyone voted for him.

Leaving politics…

His decision to leave politics came after he met the writer Sarah Paley. They planned to marry and she wanted to have a child with him.

“I didn’t want to have another kid in politics,” he said. “The child of a politician has a different life. It’s not that my two other children suffered, but it’s a burden on them. I’d come to the end of two terms [in the Senate]. Twelve years is enough.”

So when The New School job opened up, Kerrey took it and moved to Greenwich Village, where Paley also lived not far from the school.

Shortly after Kerrey got to The New School, the story broke of how the commando unit he led in Vietnam had killed about 20 Vietnamese villagers after a stealth raid in search of a Viet Cong leader. That incident, and later Kerrey’s support of the invasion of Iraq, led some at the famously left-wing school to call for his ouster.

Looking back, Kerrey said, knowing what he does now, he’s not so sure he would have taken the university post — not because of having to deal with radical student protesters and critics, but because of the sheer challenges The New School faced.

“We didn’t have a list of our alumni,” he noted. “Ninety percent of the money I’ve raised is from people who didn’t go to school here. I didn’t comprehend the sense of the challenge.”

Kerrey admitted he almost didn’t extend his contract for another five years when it came up for renewal in 2006. A second renewal, however, wasn’t in the cards.

“There was zero chance to go beyond 2011,” he stated.

…But still political

A big part of his reluctance to renew was his discomfort with having to muzzle himself on political matters.

“I like to be able to speak freely on politics,” he said.

However, at a certain point, he received the message from school trustees that, as president, he should tone down his politics, he said.

His invitation of his longtime friend Senator John McCain to be The New School’s commencement speaker in May 2006 also caused controversy — and resulted in a raucous, protest-marred ceremony. Many faculty and students felt what McCain represented was anathema to the ideals of The New School.

The conservative Republican presidential candidate bombed with the liberal graduating students, but Kerrey stressed then that free speech means listening to all sides of a debate.

Speaking after the commencement, Kerrey had told The Villager, “I think the idea of students acting up in objection to the commencement speaker is not an unusual idea. … I disagree with the assertion that he doesn’t represent the ideals of the university.”

It’s abundantly clear that Kerrey — a former U.S. presidential candidate — remains a political animal through and through. In 2007, he seriously mulled running for retiring Nebraska Senator Chuck Hagel’s seat, but decided against it, saying he would have had to uproot too quickly — his young son, Henry, was settled in school here — and that it was just too hard “to go back.”

“I still love Nebraska,” he said. “I don’t consider myself a natural New Yorker. I still like to see the sunrise, sunset.”

Before that, in 2005, he made waves when he told a New York Times reporter that he was thinking about running for mayor of New York City.

“I was very upset with the mayor at the time,” Kerrey explained. “I felt Bush’s tax policies really disadvantaged New York. Adam Nagourney called, and I said, ‘I’m thinking about it.’” But, in retrospect, he added, “I don’t think I’d enjoy being mayor.”

McCain and D.A.D.T. Speaking several weeks before the recent historic vote on the bill to repeal Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Kerrey said of McCain — a staunch opponent of gays serving openly in the military — “John is on the wrong side of history on this one.”

In the service, Kerrey noted, “You don’t have sex with subordinates — it’s against the rules. They regulate sex. … People are coming out now as gay younger and younger.”

Regarding the Arizona immigration law, Kerrey said, “I think our federal immigration policy is embarrassing; Arizona should take a role in changing it. But we can’t have 50 state laws on immigration policy. I think it’s not the province of the states.”

On terrorism, Kerrey said, the capacity to identify people coming into the U.S. to wreak damage has gotten a lot better in the last few years.

Kerrey said that during the presidential primary campaign, when he was initially backing Hillary Clinton, his statement about Barack Obama having Hussein as a middle name was misconstrued as an underhanded criticism.

Speaking to The Villager last month, Kerrey explained that what he said was meant as a positive.

“We have a Barack Hussein Obama as president,” he stressed. “France and Germany don’t.”

As for the health bill, Kerrey noted, “The federal government can’t say you have to buy insurance.” The Supreme Court will likely rule against that provision, he predicted.

If he were president, Kerrey said, to get the economy back on its feet, he would have focused on major works, like transportation.

“I would probably have come in with three or four big infrastructure projects over like 10 years,” he said, adding, “One thing you can say about a ‘Bridge to Nowhere’ — it’s a bridge and someone’s got to build it.”

On the next presidential election, Kerrey sees either Sarah Palin or Mike Huckabee as the likely Republican candidate. The nominee will likely be decided very quickly, based on the Iowa caucuses or New Hampshire or South Carolina primaries, he said.

In foreign affairs, the former senator said of Afghanistan, “You don’t have to occupy a whole country to deal with terrorists that are in that country,” adding, “I think you got to look beyond Karzai. The ‘single man’ thing is a problem. We’ve made him into this kind of hero.”

On the planned Islamic cultural and community center on Park Place, a.k.a. the “Ground Zero Mosque,” Kerrey noted, “I completely misjudged that one.”

“I wouldn’t have cared if it was moved six blocks away” from its current site, he said, calling that “a reasonable compromise.”

Politics still his passion Kerrey said he potentially has a position lined up at The New School at what he called The Institute for Liberal Democracy, but that details haven’t been finalized.

“What I’d like to do is reacquire a political voice,” he said. Currently, he noted, he’s lost that voice — lost it “a lot.”