BY GREG DAVID, THE CITY. This article was originally published on by THE CITY

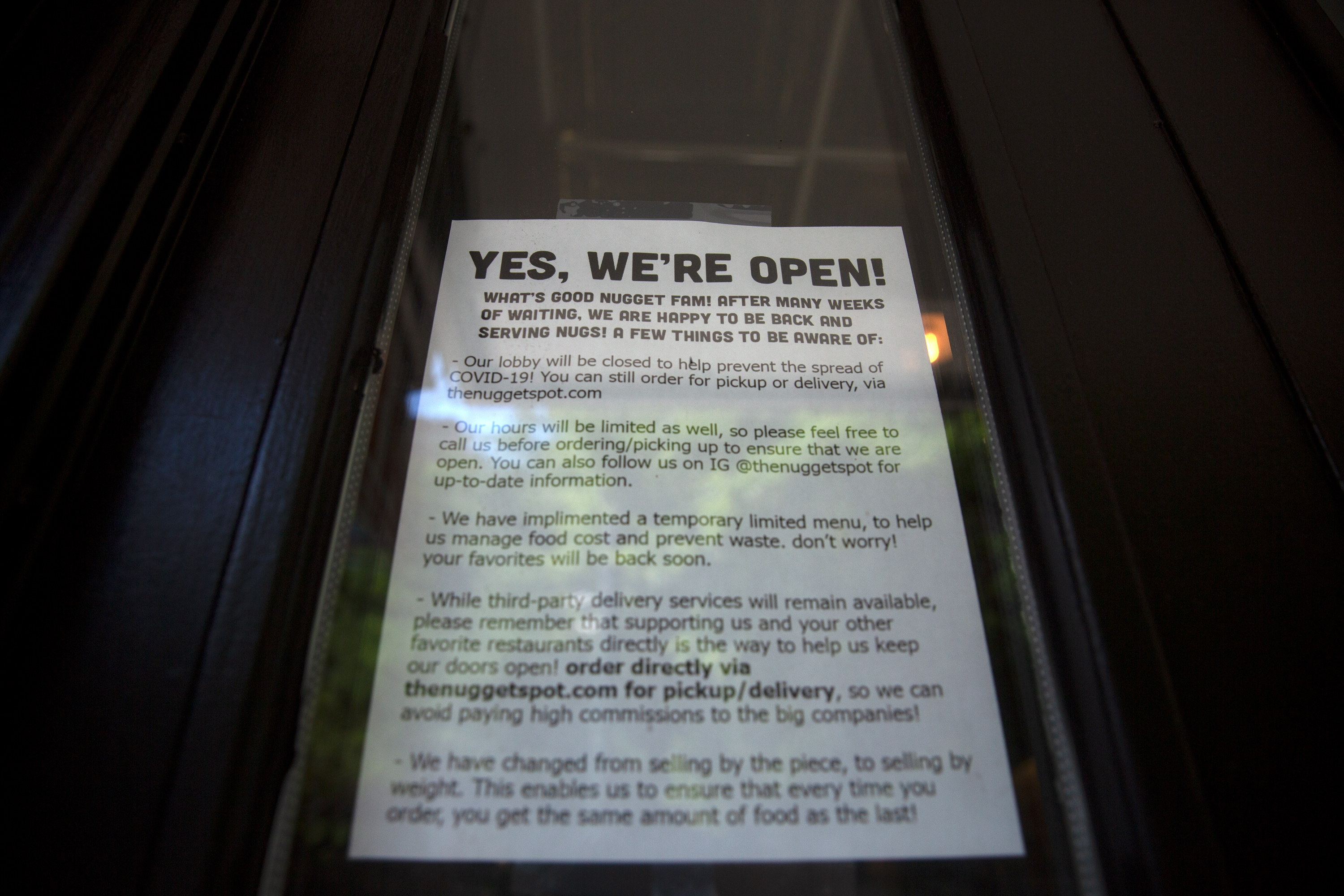

At The Nugget Spot on East 14th Street in Manhattan, business for all of June equaled one good Thursday before the pandemic.

In Long Island City, Corazon de Mexico’s take is running about 15% of what it once was, despite promotions to boost business.

Havana Central’s takeout and delivery business at its Times Square restaurant equaled about 3% of its former revenue. With outdoor dining, that number has crept up to 10%.

Despite Phase 4 of the city economy reopening starting Monday, thousands of loans from the federal government and expanding city efforts to help, many New York restaurants are within months — or even weeks — of running out of the resources needed to stay alive.

Outdoor dining has provided most with only a small boost, and the cost of renovations makes the economics of reduced capacity inside look foreboding.

For many restaurants in business districts, their customers simply won’t be returning anytime this year. And the money from the federal Paycheck Protection Program loans is running out.

“It’s a dire situation,” said Andrew Rigie, executive director of the New York Hospitality Alliance. “Fewer than 20% of restaurants paid their full rent in May.”

It’s the figure he uses to gauge how many restaurants are financially solvent.

A running tally by the food site Eater now lists almost 80 well-known restaurants that have closed permanently, and the full number of lost eateries is surely much higher.

A Key Barometer

Restaurants, always central to the identity of New York, have become a major way for people to assess the state of the city and its economy during the pandemic.

Some 28,000 restaurants across the five boroughs have city Health Department permits allowing them to operate. But the number of open restaurants may be lower since establishments do not have to notify the department when they go out of business, and annual renewals are not required until the pandemic ends.

Last week, the state Labor Department reported that jobs at all food service and drinking places had rebounded to 140,000 in June from a low of 91,000 in April. Full service restaurant employment reached 52,300 from only 22,900 in April.

However, full service restaurants employ only 30% of the staff a year ago. Some of the people reported as employed may have been on the books because they were being paid by PPP money and will be officially jobless again when the July numbers are reported.

Before the pandemic, business was thriving for many eateries.

Cynthia Shephard opened Corazon de Mexico three years ago. As head of a woman-owned business, she made a point of hiring women who had been victims of domestic abuse.

In addition to thriving on the growth of Long Island City, she had made inroads into Manhattan with catering. “Business was really good,” she recalled wistfully.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Jason Hairston’s The Nugget Spot on 14th Street did $1.6 million in business last year from a 1,000-square foot store, an exceptional number for such a small location. The shop, which specializes in chicken nuggets, also attracted 45,000 Instagram followers.

Hairston thrived on traffic from the six nearby college dorms, two local high schools and people flocking to the nighttime events on the Lower East Side.

“Sometimes we would have 50 people crowded into the place,” he said.

Like the vast majority of restaurants, both shut down in mid-March amid stay-at-home orders issued by the governor and mayor. While the city announced a couple of programs to help the industry, the key lifeline came from the federal government’s PPP loans.

A recently released database from the Small Business Administration shows that 1,500 New York City eateries received loans greater than $150,000. Thousands of others likely got smaller amounts.

The loans were forgiven if the money was used for rent — up to 25% of the loan — and payroll, which meant that some employees were paid even if they didn’t work.

Payroll Loans Running Out

The Ragtrader, on 36th Street in the Garment District, received a $690,000 PPP loan that footed the payroll and the rent. Owner Mark Fox also took about a $150,000 long-term SBA loan as the pandemic hit to cover taxes and payments to vendors.

The three-story eatery, which boasts a piano bar in the basement and a karaoke lounge upstairs, generated $8 million last year.

With outdoor dining, Fox is making up to 10% of last year’s revenue. But he’s still losing money and the PPP loan will be exhausted soon.

Business has been more disappointing for Hairston, who waited until June to reopen for takeout and delivery only, and is generating less than 5% of his previous revenue.

He doesn’t see much point in trying to set up sidewalk dining outside on 14th Street, and a bus lane means he can’t expand onto the asphalt. His $97,000 PPP loan runs out soon, and it is likely he will close again when that happens.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYThe problem isn’t just the lack of revenue. Adapting to new city regulations, outdoor dining requires money for planters, furniture and other barriers and will require additional changes if inside dining is allowed, said Jeremy Merrin, owner of Havana Central on 46th Street and several other eateries.

“We are all trying to get all kinds of shading — umbrella and canopies — so it is almost impossible to buy them online,” he said.

He has brought back only 15% of his pre-pandemic staff.

Hanging on means reaching a break-even point. Fox at The Ragtrader believes that is 20% of his former revenue. His plan for the rest of the July is a series of events, including a one-night piano bar session outside, to lure people from other parts of the city to 36th Street.

If that doesn’t work, he will close for August and reassess in September.

Rent Takes a Toll

The immediate challenge of boosting business doesn’t address the two biggest future problems restaurants must confront even if they get through the summer: the lack of people coming back to the business districts and the rent.

The Ragtrader’s clientele before the pandemic consisted of 70% commuters on their way home from their offices, 20% tourists and 10% shoppers. Almost none have returned to the area.

The New York Times, located just a few blocks north, has told its staff that with only a few exceptions they will not be able to return to the building until next year.

Hairston doesn’t know how many of the six dorms will be occupied in September. But he does know many high school students won’t be back and that other venues are unlikely to attract large crowds. “It’s really a bad situation,” he said. “Who knows what will happen.”

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYRestaurants can reduce their costs for food and staff, but they are stuck with the high rents they agreed to when business was better.

Some landlords are being accommodating. Havana Central is paying its landlord 10% of its revenues each month. Every Friday, when Shephard of Corazon de Mexico goes to the bank to deposit the week’s receipts, she puts aside a portion to send to her landlord.

A ‘Massive Stimulus’ Needed

Yet the Hospitality Alliance’s survey showed only 10% of landlords have been willing to renegotiate leases, even though their chances of replacing any tenants they evict are small.

Landlords, Rigie notes, have their own obligations — especially mortgages — and reducing rent could slash the value of their buildings. “Maybe they are waiting to see what the situation will be like in the future,” he said.

Like cities and states with massive budget deficits or unemployed workers receiving an extra $600 a week in jobless benefits that expire this month, restaurants are anxiously waiting for another aid bill from Washington.

“We need a massive stimulus package from the federal government to provide long- term economic support for restaurants and bars at the epicenter,” Rigie said. “And bring the banks, landlords and commercial tenants to the table to restructure leases and mortgages.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.