BY JERRY TALLMER

Historic, hard-to-kill theater renovates, rises again

When the Ragu ran out, the Mambo Mouth moved in.

That’s a shortcut way of saying the shuttered Actors’ Playhouse, that ghost-ridden little Off-Broadway bandbox just below Sheridan Square, breathes once more — and history rolls on.

The dear dead wedge-shaped 60-plus-year-old theatrical shelter’s recent comeback show, Frank Ingraciotta’s autobiographical Sicilian-American “Blood Type Ragu,” having unexpectedly run out of — well, customers — the hush-hush new occupant at this writing is Latino superstar John Leguizamo, working up another of his own autobiographical firecrackers under the well-worn interim title “Work in Progress.”

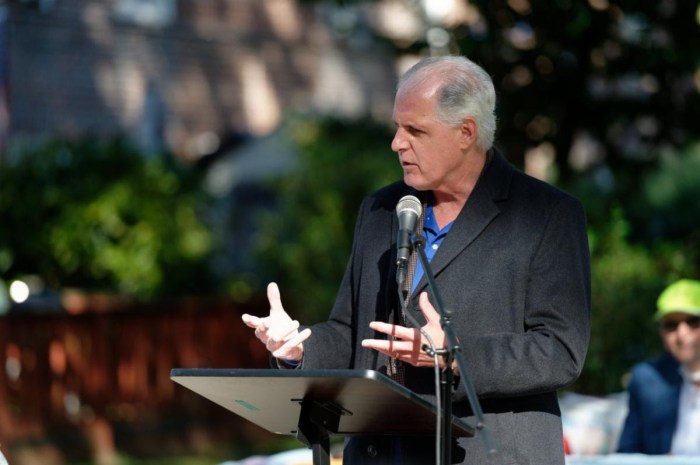

Lawrence Page, the 35-year-old self-styled Black Cowboy who reckons he’s spent nearly three-quarters of a million dollars acquiring and refitting the 170-seat premises at 100 Seventh Avenue South, is a man who likes history — even if he never saw a show there before he took over the joint last year.

He has also, over the years, acquired 150 cowboy hats, and can usually be found walking around under one of them. And, yes, he’s black. Like Barack Obama.

History lingers everywhere in the Actors’ Playhouse, through the shapes and shadows and voices of the Off- and Off-Off Broadway actors, living and dead, who once graced this stage en route the big time: Al Pacino, Eric Bogosian, Matthew Broderick, Everett Quinton, Sudie Bond, Bob Kulp, James Earl Jones, Rosetta LeNoire, Will Holt, Dolly Jonah, Gerry Jedd, Will Hare, Josh Kornbluth, Colleen Dewhurst…

And on and on, along with everybody who was in or had anything to do with a four-decades-before-Gharid prison drama called “Fortune and Men’s Eyes,” by a young Canadian named John Herbert (produced by a young Greenwich Villager named David Rothenberg), out of which came the Fortune Society that is helping former inmates to this day.

“Blood Type Ragu,” the one-man show that reopened the shuttered entrance at 100 Seventh Avenue South — that strange speak-easy-type entrance, where you go down a half-dozen steps and then up a good many more steps — had a two-month run back in February and March of this year.

“I was as shocked as anybody, as shocked as Frank Ingraciotta was” by the sudden closing, says Lawrence Page. But not too shocked. “I actually gained on it,” says Page, “because of the guarantee clause. An $80,000 deposit. I put it back into the restoration.”

That restoration includes, by Page’s citation:

Redoing the entire entrance hallway.

Removal of 4 inches of sheetrock from the walls.

Reinforcement of walls and leaky ceiling.

Resurfacing and reglazing brick walls.

Redoing floors down to original cement.

Replacing all 170 seats with 165 new ones, each with its own cup holder.

Creating a new straight-edged proscenium “to replace the one that was crumbling and falling down.”

Two new dressing rooms.

Two new bathrooms.

Brand new air-conditioning system.

New lighting system.

New sound system.

New sidewalk awning.

There’s a new sidewalk awning, be it noted, with the apostrophe at long last in the right place, at the end: “Actors’ Playhouse” (plural). In the course of which, Page discovered that that very awning was and had long been protected as “landmark signage” under the landmark laws.

Even before the sudden departure of “Blood Type Ragu,” Page had heard that John Leguizamo was up to something or other — trying out new material before a live audience — at the Barrow Street Theater in Greenwich House, just a couple of blocks south of Actors’ Playhouse.

Page took a stroll down there. He made himself known to Leguizamo. He said: “I have a nice little theater just up the street. Why don’t you come and check it out?”

Which Leguizamo did.

“And three weeks ago, he started working here; did ten shows so far; has another 11 to go. It’s his one-on-one process: feel the audience out. He talks about his experiences at the start of his acting career; about the films he’s made; about how his fellow actors made him realize who he was, what’s his job as an actor, why he’s here.”

Page has no illusion that Leguizamo’s “Work in Progress” — whatever its ultimate title and content — will stay at Actors’ Playhouse. He knows it will go into some larger theater, maybe on Broadway, maybe not. But he’s not worried.

“I feel a holiday show coming on, with lines around the corner. ‘The Gayest Christmas Pageant Ever.’ No, I’m a straight guy,” Lawrence Page appends.

He was born October 18, 1974 — or maybe 1975 — in Tampa, Florida; was raised in Roslyn, Long Island, went to school in Freeport, Long Island. He’s the son of a “custodial worker” mother — a cleaning woman — to whom he owes a great deal. He saved $7,000 as a kid that enabled him to make DVD movies like “Confessions of a Call Girl” that raked in enough cash for him to buy cowboy hats and little old Greenwich Village theaters to the tune of, he says, a $500,000 purchase price, plus $200,000 in restorations.

He used to live “on a ranch” in Pennsylvania. He now lives — alone — in Hamilton Park, Jersey City — “an old history town that reminds me of Harlem in some respects.”

If all else fails, he’s going back to what he calls “the reality TV show” he was shooting at the dormant Actors’ Playhouse last fall. It was in fact called “Actors’ Playhouse” and gave rein to “African-American and urban actors.”

Like a black Actors Studio?

“That’s right,” said Lawrence Page, limping off on an ankle that had been sprained when he’d tripped over something or other on stage at the Actors’ Playhouse.

The historic, hard-to-kill, slice-of-pie-shaped, 165-seat Actors’ Playhouse at 100 Seventh Avenue South.