By PAUL SCHINDLER | Despite a mushrooming of candidate debates around town, the race for City Council speaker is limited to just 51 voters. But that’s not to say that this year’s seven announced candidates have suddenly decided to open up to a wider constituency an exclusive prerogative councilmembers previously guarded jealously. In fact, individual members have often enjoyed little leeway in casting their vote for speaker.

“In many parts of the city, councilmembers aren’t allowed to think for themselves,” observed Ken Sherrill, a Hunter College political scientist and longtime student of New York municipal government.

Traditionally, county Democratic organizations — especially in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx — played the dominant role in the battle for Council control. When Christine Quinn, the first woman and first openly L.G.B.T. member to lead the Council, won her hard-fought contest in late 2005, the support of the Queens organization was instrumental in helping her dispatch her prime competitor, none other than Brooklyn’s Bill de Blasio. Borough party leaders certainly won’t let a little public exposure to the speaker’s contest dampen their resolve to play an inside game again this year.

But a key conceit in the current political narrative is that 2013 is different. A new mood among the public. A new direction. A new mayor. De Blasio himself would seem philosophically aligned with charting a new course in choosing the Council speaker. Not only did he find himself at the short end of the stick when a leader was last chosen, but his campaign this year, stuck in the doldrums for months, gained critical traction as he contrasted, in debate after debate, what he described as his inclusive style of leadership and decision-making with a heavy-handed control of the Council he saw from Quinn, who for months had been the clear frontrunner.

De Blasio’s specific criticisms of the speaker focused on her delay in allowing a vote to guarantee most workers in New York paid sick days, her cautious response in addressing the NYPD’s stop and frisk policies, and her use of discretionary allocations to individual members to reward allies and punish dissenters. Boiling down the particulars, however, it’s clear the mayor-elect was faulting a political regime in which a Council speaker relies on powerful county organizations to maintain their reins on power.

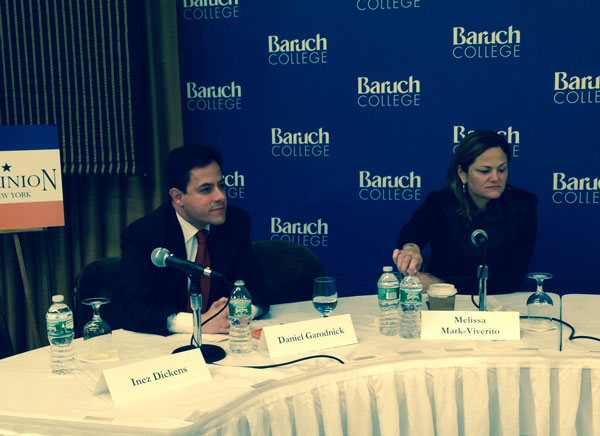

De Blasio has widely divergent relationships with the seven speaker candidates — the most distant being that with Harlem’s Inez Dickens, whose opponent he endorsed in the September primary — but in debates each has been careful to acknowledge the “mandate” he earned in his sweeping 50-point victory over Republican Joe Lhota. Still, at a Baruch College forum sponsored by the good government group Citizens Union, only Mark Weprin of East Queens and East Harlem’s Melissa Mark-Viverito said they or their senior staff had spoken about the contest with de Blasio or his senior staff.

Weprin said he and the mayor-elect have spoken directly, while Mark-Viverito was more coy — though she can afford to be. The first councilmember to endorse de Blasio in defiance of Quinn, she is widely thought to be his favorite — and the favorite — in the race.

“I see myself as the progressive candidate, who has an inclusive vision and a record of accomplishment,” she told the crowd at Baruch and repeated in much the same formulation the next evening in an NY1 debate. To credibly make such a claim is a leg up in a year when the city elected the “unapologetic progressive alternative” as mayor and what observers consider the most progressive slate of City Council candidates in recent memory as well.

In the current Council, the Progressive Caucus, co-chaired by Mark-Viverito and Brooklyn’s Brad Lander, numbers 11 members including Lower Manhattan’s Margaret Chin. The caucus saw its greatest success with the override of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s veto of a package of police-community relations reforms championed by Lander and Jumaane Williams, another contender for speaker. Out of that caucus, in recent weeks, has emerged a “progressive bloc” of 20 or more members — including newcomers to the Council — who have pledged to stand together in support of the same candidate in the speaker’s race.

That pledge, if it can genuinely be carried out, represents a fundamental challenge to the county Democratic leaders. Hunter’s Sherrill said the progressive bloc’s bid reflects members’ “sense that traditional political machines are greatly weakened. And they are trying to fill the vacuum.”

Beyond the specifics of the bloc’s ideology, its emergence squares nicely with a mood among voters for greater government transparency and among councilmembers themselves for greater input into how the body is run. A week before the November election, several dozen members and candidates just days away from winning their seats gathered at City Hall to embrace a package of procedural reforms, chief among them one that would “take the politics out of member items” by allocating discretionary funding for Council districts on a “fair and objective basis.” The package, based on process and not outcomes, drew the support of at least 30 future councilmembers — a broader spectrum than the progressive bloc itself.

An advocate for transparency and accountability, Citizens Union hails the vigorous discussion about revising Council rules. On the day it sponsored its speaker’s forum, it also released the findings of the questionnaires victorious Council candidates completed earlier in the year, which it said demonstrated “widespread support for reforms previously thought to be unachievable.” The group found 44 or more members of the 2014 Council supporting steps to strengthen committees relative to the speaker and more than three-dozen advocating greater member authority in drafting bills as well as more equitable and transparent allocation of discretionary funds to each Council district. Only on questions of limiting additional stipends to members and requiring greater disclosure of outside income did support for reform just barely win a majority.

Discussing proposed reforms at the Baruch forum, the speaker candidates were most tepid on this last category, which — unlike proposals for decentralizing power from the speaker to the other members — would instead require sacrifice on the part of the Council’s rank and file.

At several forums, the tenor of each candidate’s remarks about reform and the Council’s responsibility to act as a check and balance on the mayor has been telling.

Mark-Viverito speaks proudly about being first out of the blocks for de Blasio and, at Baruch, pointed to “a clear mandate in this city that we need to move in a new direction.” While insisting she would not hesitate to “stand up and defend what the body wants,” she predicted the Council and the new mayor’s goals would largely be “aligned.”

Dan Garodnick, an East Sider generally considered to be in the hunt with Mark-Viverito, talks less about ideology than about his skills as a “creative problem solver,” mentioning his efforts at organizing tenants of Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village in a buy-out bid when their rent-stabilized status appeared threatened. Asked if reforms could weaken a Council already disadvantaged relative to the powers of the mayor, Garodnick responded, “That question hits right at the challenge we have. But that speaks to the skill of the speaker.”

Queens’ Weprin, the third candidate given a decent shot at prevailing, cites his 16 years in the State Assembly prior to joining the Council in 2010 to claim his bona fides as a progressive, but lays greatest emphasis on two other factors — use of his Albany know-how to advance the city’s interests there and the eight years he is still qualified to serve in contrast to the term limits most of his rivals face in 2017.

“I will say what some others won’t,” he said. “I will never run for mayor.”

Three of the other candidates — Harlem’s Dickens and Annabel Palma and Jimmy Vacca, both of the Bronx — have typically sounded less urgent calls for thoroughgoing Council reform. Both Palma and Dickens supported Quinn’s mayoral bid, and Dickens, in particular, can sound defensive when asked what changes are needed. “Bill de Blasio has an aggressive, progressive agenda,” she said at Baruch. “But he has spoken out against the Council rubberstamping the mayor. I don’t believe he wants to make that mistake.”

Vacca, who is both plainspoken and colorful, raised the most vivid caveat about pushing power-sharing on the Council too far, arguing, “I don’t want to be Boehner, who goes into Obama’s office and says he does not have his House behind him.”

The seventh candidate, Brooklyn’s Jumaane Williams, who established progressive credibility over the past two years with his leadership on the police reform question, is the hardest candidate to peg. Entering the race last week, he was immediately engulfed by controversy over past statements voicing opposition to marriage equality and a woman’s unfettered right to choose. Rosie Mendez, a lesbian representing the Lower East Side, told Capital New York those positions were a deal-breaker for her, and some who attended Williams’ presentation to the Progressive Caucus this past weekend said he struggled to explain his thinking on either question, at points becoming emotional.

Among Mendez’s five L.G.B.T. colleagues on next year’s Council, only Corey Johnson, who replaces Quinn on Manhattan’s West Side, would speak about the Williams flap, saying, “My principles in this decision with regard to marriage equality and choice are fundamental to me and who I am.” One longtime Brooklyn gay Democratic activist speculated that other councilmembers are playing the matter low-key out of recognition that Williams is not in it to win. His goal, that source speculated, was to highlight his concerns about police relations with communities of color — an objective now likely overshadowed by his ham-handedness on social issues.

Outside observers and several councilmembers who spoke on background all agree that Mark-Viverito has the best shot at winning — but none would say the prize is yet hers. Numerous recent press reports last week chronicled the breakdown of efforts to set up a meeting between the progressive bloc and the Queens organization headed by Congressman Joe Crowley. One councilmember told this newspaper that “freeze is beginning to thaw.” With a growing Hispanic population in his district, the member said, Crowley would like to “make history” by helping elect the first Latina speaker.

“I don’t know if de Blasio is behind her, but I would think he would be, and his lift could help at the end,” the councilmember said.

Another member, however, insisted that Mark-Viverito could prevail only if de Blasio stepped in on her behalf. According to that account, her Council colleagues are uncomfortable that she is too far to the left and has proved herself both “strident” and “aloof.” The mayor-elect, this source speculated, may be reluctant to step in because a Mark-Viverito speakership would immediately confront him with issues such as non-citizen voting in municipal elections, a question he is not interested in taking up at the outset of his administration.

The possibility that Mark-Viverito’s candidacy could be derailed because she is too progressive alarms Allen Roskoff, president of the LGBT Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club and a fierce critic of Quinn in her years as speaker.

“What I fear is that the county leaders will be able to pick off members of the Progressive Caucus,” he said, pointing to Crowley as “the chief culprit” in that effort. The Queens leader, Roskoff charged, is angry that some in his county have bucked his organization in favor of the progressive bloc and has threatened to put up primary challenges even against councilmembers from other boroughs.

Roskoff also denounced what he termed “red-baiting,” such as the claim made by Queens Councilwoman Karen Koslowitz that Mark-Viverito — who only in recent weeks began to join her colleagues in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance — had earlier refused to do so because she felt that Puerto Rico, where she was born and raised, should get its independence.

George Arzt, who served as Mayor Ed Koch’s press secretary and runs a communications and government relations firm, said of the challenges facing Mark-Viverito’s candidacy, “The Pledge of Allegiance is a factor. Not a significant factor, but a factor.”

The bigger problem, according to Arzt, is her relationship with colleagues. “What do we say on report cards? She has a reputation for not working and playing well with her colleagues,” he said.

Asked whether he thought de Blasio would intercede on her behalf, Arzt said, “I don’t believe it’s in his interest to get involved. He doesn’t need that war right now, and the other question is: Can she herd the other 50 cats? If she can’t, the mayor has to step in and give away the store on every vote.”

As did several others, Arzt suggested that a dark horse — Councilwoman Julissa Ferreras, who represents Elmhurst and Corona in Queens — could prove an acceptable compromise to county leaders and to the Progressive Caucus to which she belongs. Her selection, Arzt said, would also satisfy the mayor-elect’s interest in seeing a member of the Latino community win a citywide leadership role for the first time.

A good number of councilmembers and major outside players, including labor giant SEIU 1199, would dispute Arzt’s assessment of Mark-Viverito’s ability to effectively lead the Council.

Ken Sherrill observed that no matter how close de Blasio is to Mark-Viverito, it’s not clear what he is looking for in a Council speaker. Noting the tremendous fiscal pressures the new mayor will face, he said, “I would think he would want a speaker who would restrain the leftward impulses of the Council.”

Sherrill also raised the possibility that a progressive mayor imposing a progressive speaker on the Council ironically might not serve progressive interests. “New York already has a strong mayor under the City Charter,” Sherrill said. “Be careful what you wish for.”

If de Blasio wants to have a say, however, Sherrill has no doubt how that would work out.

“I don’t think there will be many people who will want to cross him here,” he said. “If he wants it, I think he’s going to have his way.”