BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | Heat and the threat of afternoon thunderstorms didn’t deter an estimated 12,000 people from visiting Governors Island on Sat., May 26, the opening day of the island’s 2012 season. Awaiting them were a family festival in Nolan Park with music, theater, dance and crafts, the 5Boro PicNYC in Colonels Row — consisting of craft beer, more than 20 food vendors and bluegrass music — and the monumental sculpture by Mark di Suvero, who is back on Governors Island for a second year.

But for some people, the star attraction was the chance to see the inside of Castle Williams, which had been closed during a three-year renovation.

The landmarked fort dates back to the early 1800s and was named after its designer, Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Williams, a great-nephew of Benjamin Franklin, who shared some of his great-uncle’s scientific and engineering genius.

Castle Williams and Fort Jay, a slightly older fort, are the core of the Governors Island National Monument, which make up approximately 23 acres of the island that are under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service.

Previously, forts had been star-shaped, such as Fort Jay. Williams, who was the first-ever superintendent of West Point, figured out that a round fort on the western flank of Governors Island, facing New York harbor, would allow coverage in all directions. His round forts model became prototypes for coastal fortifications.

Castle Williams is built of red sandstone, with walls that are seven-to-eight feet thick, according to Michael Shaver, supervisory park ranger for the National Park Service.

“One of the reasons why circular towers didn’t work in the old days was that if you penetrated them, they would collapse,” he said. “Williams built arches into the casemates so that in the event that you were lucky enough to go through seven or eight feet of sandstone and breach the walls, the building wouldn’t collapse.”

Nevertheless, Williams’ supervisors were dubious, Shaver explained.

“His superiors were old fellows left over from the Revolution,” he said. “They were always fighting the last war. They had some doubts about [Williams’ design].

Shaver continued, “To prove his point, he had two Navy ships fire on the fort from about 400 yards away. All they succeeded in doing was to knock a cannon off its carriage. Williams sent the Secretary of War a newspaper clipping that said the barrage had destroyed a cannon.”

At the bottom of the clipping, the Secretary of War purportedly wrote, “It didn’t destroy a cannon! It knocked off a cap plate and lock screw and knocked it off its carriage. It’s still serviceable.”

Castle Williams has 78 openings, known as “embrasures,” for guns positioned in 39 casemates on three tiers. The high ceilings and openings between the casemates were intended to help dissipate the smoke from firing the guns, according to Shaver.

Telescopes mounted outside Castle Williams that are trained on Castle Clinton in Battery Park and on Fort Gibson on Ellis Island show how these and several other forts positioned according to Williams’ plan provided an impregnable defense of New York Harbor. All of them were built prior to the War of 1812, when the threat of war with the British was imminent.

The plan worked. The British burned down Washington, D.C. and attacked Fort McHenry in Baltimore, but they spared New York City.

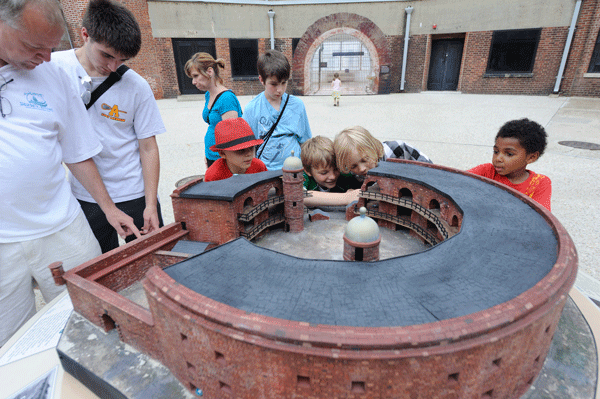

A model of the fort as it looked originally is situated in the middle of the Castle Williams courtyard. Large murals reference key dates in the fort’s history as it evolved from its initial mission, which was to defend New York Harbor, to its later function as a prison for Confederate soldiers and Union deserters during the Civil War.

Later on, during the 20th century, the fort was used as a prison for the U.S. Army and therefore became known as the “Eastern Alcatraz.”

“In 1947, the Army gutted the entire building and took out the old, oak floors from 1812, poured in reinforced concrete floors and put in the jail cells that you see,” said Shaver, as he led a tour of the second and third tiers of the three-story structure. The solitary confinement cells, whose walls are composed of solid metal, have protrusion marks from the prisoners banging on the walls.

The U.S. Army left Governors Island in 1966, after which the island was taken over by the U.S. Coast Guard until 1997. During the Coast Guard’s tenure, Castle Williams was used intermittently as a community center and also as a grounds-keeping shop, but it wasn’t properly maintained; eventually, the roof deteriorated and water seeped into the walls.

U.S. Congressman Jerrold Nadler obtained $6.1 million from the federal government to rehabilitate the structure. The money was used to remove lead paint, asbestos and other hazardous materials, to replace electrical wiring and windows and to repair the structure’s stonework and bricks. The funds also financed exhibits in the courtyard and on the first floor that tell the history of Castle Williams to this day.

Entrance to Castle Williams is by timed ticket. A separate ticket is needed to tour the interior and climb to the roof with its views over the harbor. Tickets are free and are available at a gazebo next to the fort. Castle Williams is open from 10:30 a.m. to 4:15 p.m. whenever Governors Island is open. For more information, go to www.nps.gov/gois.