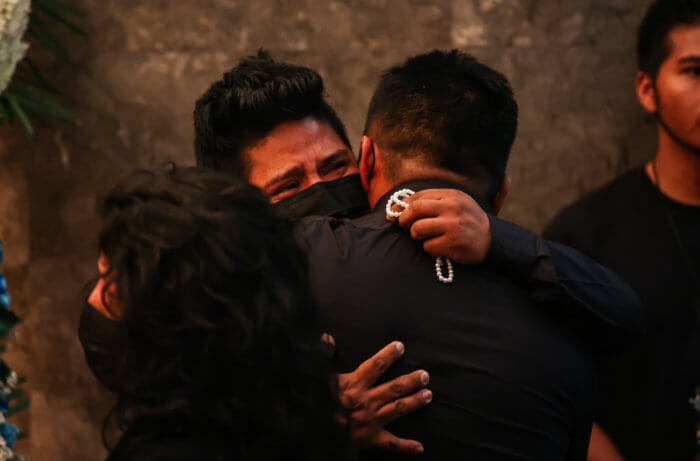

Not everyone who piled into a somber Upper West Side funeral home on a muggy Sept. 8 evening knew Ricardo Solano, a 31-year-old food delivery worker from Mexico’s Huehuetepec community who went missing on Aug. 13 and was found dead days later from an alleged robbery in the Washington Heights.

As Solano’s brother gave a tearful goodbye among a sea of fellow countrymen and women amid the sorrowful crooning of Mariachi horn trumpets and tenors at his funeral, fellow delivery workers — mourning the loss of a brother in profession and country — have noticed a disturbing pattern of rising fatalities among their tight-need circle during work shifts.

“It’s sad. To see our brothers in a coffin, knowing their final moments were probably scared … worried about their family and who will take care of them,” said Eduardo Marias, 25, who often does deliveries in Washington Heights and the Bronx. “I didn’t know him, but I saw myself in him. I saw his relatives crying and other (delivery workers) crying.”

A most tragic year

In 2022, 18 NYC-based delivery drivers have died — all of them immigrant men, a majority of whom are no older than 30 — under hazardous circumstances such as hit-and-runs, assaults and attempted robberies.

In a span of nine days, from July 4-13, four delivery workers — Christian Catalan, Lucian Morales Feliciano, Jose Angel Victoriano and Eduardo Valencia — were killed in a traffic accident or hit-and-run in Brooklyn and the Bronx. Another, Tiburcio Castillo, was assaulted and killed in a robbery on July 13, and police still have no leads on who attacked him.

Ernesto Santiago dreads any route that takes him along a troubling stretch of Southern Boulevard and 179th Street in the Bronx. A day before another cyclist was severely injured colliding with a car in that same West Farms intersection, Santiago said his “life flashed before his eyes” during a delivery when he was clipped by a red Honda that never broke its stride.

Santiago, 22, has only been doing gigs with DoorDash and Uber since emigrating from Guatemala this summer. His hopes are to earn enough to bring his wife and three kids to the U.S., but says in just three months he’s had several close encounters at night, on poorly-lit streets.

“I’ve had others doing this for three, five years who have helped me adjust. It’s scary at night sometimes, people try to provoke you, but there’s also a strong community that is willing to help,” said Santiago. “I’ve heard the stories of others who have been less fortunate, who are gone. You don’t want that to be you and leave your family like that.”

For 10 years, Sergio Garcia has ridden the rubber off his bike navigating delivery to delivery in New York City — the nation’s busiest food delivery corridor. Each trip is different, but there is an ever-present sense of danger.

I mean, every time you change, you know?” said Garcia. “There’s so much bike-stealing, there’s a lot of attacks on people doing their job, and it feels like we’re not being seen or heard.”

Garcia has found a community El Dario De Los Delivery Boys — a group of delivery workers living or working in the Bronx, Upper East and West sides of Manhattan and Washington Heights — who chronicle the speed bumps and roadblocks preventing delivery work as a sustainable and safe profession.

When a courier’s bike is stolen — which impacts their ability to accept gigs and is not a loss covered by most third-party delivery apps — Delivery Boys sounds the alarm in group texts, Facebook posts and alerts. They hear criticism of their driving — warranted or unwarranted — and give advice on which streets are most dangerous.

“I see many criticizing that the delivery drivers … are inconvenient, irresponsible … but people do not take their precautions either by running red lights,” said Sai Garcia, another delivery worker. “I have come across people who walk in the bicycle lane and drivers who do not touch the horn at a distance so as not to have accidents and still get annoyed, and not to mention the drivers who (merge) without checking if a cyclist is coming in the bike lane … but (we) deliverers are the only irresponsible ones?”

Help is on the way?

The industry has also increasingly become a place for mourning those lost in a dangerous and often unprotected and uninsured gig economy. Last year was a landmark one for NYC food delivery workers, as the City Council passed a set of bills in September 2021 requiring restaurants to give workers access to bathrooms and guaranteeing they receive full tips.

In 2023, NYC delivery workers could soon see more change to their pay wage scale.

Delivery workers are paid $7.09 per hour, excluding tips, which factors on average to $14.18 per hour with tips. Under a proposal by the city Department of Consumer Worker Protection, workers could receive a minimum pay rate boost to $23.82 an hour by 2025. A public hearing will be held in City Hall on Dec. 16.

Seattle became the nation’s first city to implement a minimum wage plus tips and compensation protections for app-based delivery drivers of DoorDash, UberEats and Instacart this summer — it goes into effect in 2023.

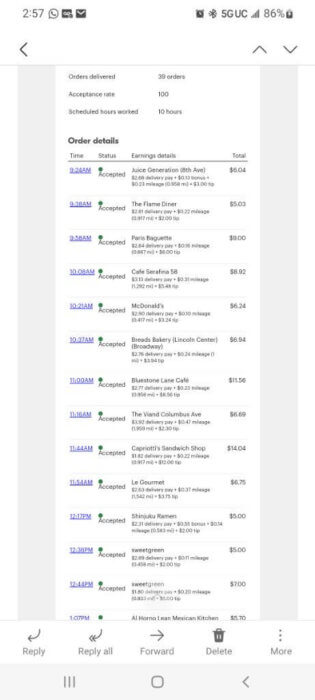

While higher wages could allow some delivery workers to relax their shifts, others like Sergio Garcia — who has done as many as 39 delivery shifts in a 10-hour day — says more needs to done to prevent delivery worker fatalities and also increase public safety resources.

Roughly 54% of NYC food couriers who were surveyed in a Los Deliveristas/Workers Justice Project-Cornell report said they were victims of bike theft, and about 30% said that they were physically assaulted during robberies.

When Tiburcio Castillo, an immigrant dad of four children between the ages of 5 and 13, went missing riding his bicycle from his Manhattan job to his South Bronx home, his wife located him after a seven-day search in a coma at Lincoln Hospital, where he remained brain dead.

Navigating NYC roadways

Some couriers blame poor city infrastructure and notoriously aggressive New York City drivers as a leading cause of fatal accidents, and add that underlit sidewalks make them prime targets for bike thefts and robberies.

Couriers often find themselves on the hook when things go awry, even if they’re not at fault. A whopping 49% of respondents reported having been in a collision while on the job, and 75% of those respondents said they had to pay for their medical care out of their own pocket.

Others believe that some couriers do not take full caution — including riding without helmets and driving recklessly through busy city streets — and mistakes happen when riders feel rushed or hurried to complete multiple deliveries in a given window.

“I work in Manhattan doing delivery and the truth is there are many countrymen who go too far and do not even bring a helmet,” said courier Filiberto Contreras. “You just have to be more responsible and be more careful because it is difficult for them to wait for the light.”

Delivery workers are overrepresented in workplace fatality rates, where they and other good-carrying drivers accounted for 1,005 fatalities, or 20% of all workplace fatalities from 2015-2019, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

When delivery worker Elias Castillo lost his life in a street fight in September, a GoFund Me for Castillo’s vigil and funeral services, as well as repatriation, were arranged by the community within hours.

“Some people can’t afford funerals. They can’t afford to say goodbye, so we try to help out as much as we can,” said Sergio Garcia, who has often assisted with vigils and funeral accommodations for his fellow “Delivery Boys.”

One member of Castillo’s family told the Bronx Times, a major hurdle in finding Castillo’s whereabouts was the persistent language barrier between non-native speakers and law enforcement. But also for loved ones separated by geographic borders anxiously awaiting next steps.

In many of these cases, families of the victims told the Bronx Times they wouldn’t have known about their death, as information from police isn’t always forthcoming or reliable they say.

“(I try to tell the families) go to all the hospitals and the morgues. It is a very hard moment, and nobody wants to go through it, but you have to make sure you know it’s (your deceased loved one),” said Magadelina Ramos, the widow of a delivery courier who died in a robbery on Willis Avenue in early 2022. “The police do very little to say nothing to help you. I still don’t know really what happened to him months later. But I know he died trying to feed us and provide (for) us.”

For a lot of Latino countries, honoring the dead is a big part of culture, where they celebrate deceased loved ones in their final resting place and offer “ofrendas,” or items that the deceased loved in life. For some religious immigrant families, cremation is often an option they won’t consider, and in places with a large indigenous population like Guatemala, it’s important to have a body to mourn, non-native couriers told the Bronx Times.

Steps to sustainability

On late-night shifts, delivery boys will convene at hubs like 125th Street and Marginal Street providing water, linguistic support and a watchful eye.

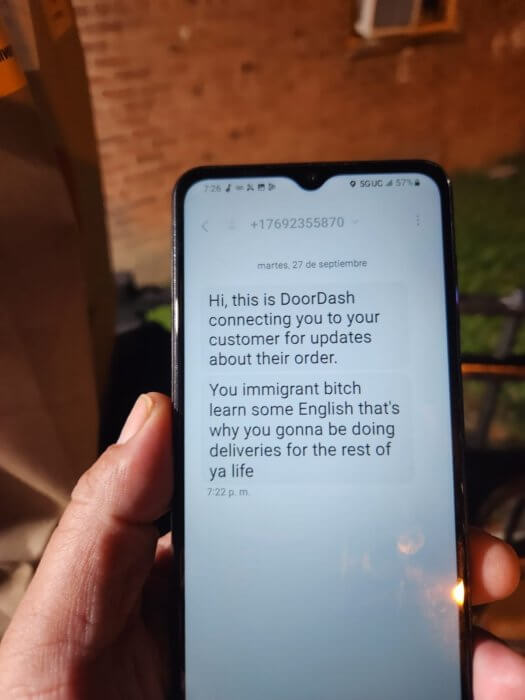

In an effort to improve worker safety, DoorDash introduced changes to its employee portal that allow Dashers to block aggressive, rude or potentially threatening customers.

“We’re clear-eyed about safety and recognize there will always be more work to be done to help make dashing as safe as possible,” the company said in its announcement. “That’s why our teams are constantly working on new technology and safety features to help Dashers stay safe before, during, and after every dash.”

For some in the NYC courier community, the city is better positioned to make systemic changes for an industry of gig workers where low wages have many couriers scrambling to work six to seven days a week, traveling crosstown and in between boroughs in less-than-ideal conditions.

“You wonder if you’re going to be next,” said Manny Reyes, a Bronx-based delivery worker. “I’ve only been in this country for six months, I do shifts for four or five different companies, and my wife (in Guatemala) always asks if I’m being safe and always worries that she’s going to hear bad news any day now.”

The major app companies have vastly different definitions of coverage for workers in case of emergency — if they offer any insurance at all. Grubhub and Relay, two major players in the industry, are among those that do not carry occupational or auto coverage, according to legal advocates, leaving workers uncovered — except in California, where some insurance is required by law.

And gig workers could gain more protections as the Biden administration is floating a new employee classification system, where a new test “considers factors such as how much control workers have over how they do their jobs and how many opportunities they have to increase their earnings by doing things like offering new services,” according to the The New York Times.

The announcement, economists predict will likely be a blow to large companies like Uber and Lyft who have lobbied against attempts to tame the gig economy, and led to battles with NYC leaders.

This article was updated on Nov. 23 at 12:41 p.m.

Reach Robbie Sequeira at rsequeira@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4599. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes