BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC | The ubiquitous sound — a cellphone ringtone — rang out in Bryant Park, but the person on the other end would have surprised historians. It was, after all, a call from Gertrude Stein, who passed away over 70 years ago.

Okay, so maybe it wasn’t Stein, but rather an actor performing a monologue envisioning what the groundbreaking writer would say if she were here, now.

Stein — like many other famous and important figures (mostly men) — has been immortalized in sculpture, but in the midst of the city hustle, how many of us stop and pay attention to them? Talking Statues is looking to change that by engaging New Yorkers and tourists alike with history.

David Peter Fox began Talking Statues in Copenhagen in 2013, with the idea of giving “voice” to the statues, according to the project’s press release. Writers would create short monologues and then actors would perform and record them.

After Copenhagen, the project spread to Helsinki, London, San Diego and Chicago, with Talking Statues officially starting in New York City on Wed., July 12 (visit newyorktalkingstatues.com for statue locations and info).

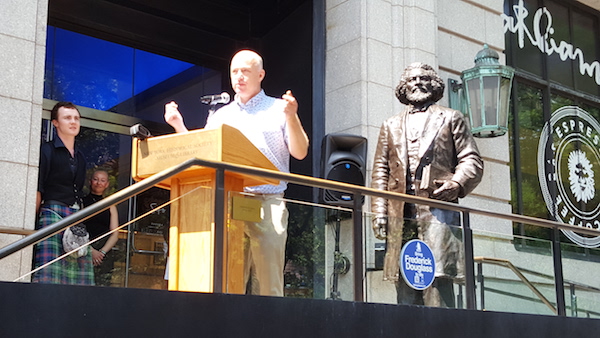

“It’s been a long journey,” Fox said at the morning launch at the New-York Historical Society. “The project is a present from me to New York City.”

Fox told this publication afterwards he worked for two years to bring his project to this city. It took some time to get permission and to find the actors, he said. Fox said some 600 actors applied for the gig.

One of the actors who made the cut was Stacey Lightman, who performed the monologue conceived for Stein at the launch. “I loved it,” she said of the process. “I played Gertrude Stein in a play a year ago — it seemed like kismet. It was a thrill to record [her].”

She noted that people go by statues but “don’t see them.”

Fox said 35 statues will be animated throughout the five boroughs. He declined to provide details about the project’s funding.

Here’s how it works. Near the statue, there is a sign with a link, which can be typed into your smartphone’s Internet browser. There is also a QR code that can be scanned by your device after you download the app. You receive a call — complete with a picture of the statue and the person’s name — and then hear the monologue.

(When asked about those without smartphones, Fox said later by phone, “There is no alternative, unfortunately not. The system is based on this technology.”)

GERTRUDE STEIN, BRYANT PARK | It took this reporter a few tries to get the call but then: “I am sitting, I am thinking. Sitting thinking thoughts of thinking, bits of thoughts, thoughts flitting, thinking, thinking, thoughts linking. This is how I think, thoughts heard, thoughts blurred, thoughts like birds, becoming words.”

The monologue, written by Marc Acito and performed by Lightman, also includes a bit of biographical information. Stein was American but moved to Paris in 1903. She was a poet, a playwright, a writer, and the host of the salon that was graced by the artistic and literary lights of the era — Picasso, Matisse, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald among others.

In 1934, she returned to America and toured the country but went back to France. “But as I say ‘America is my country, and Paris is my hometown,’ so I returned to Paris, never to see America again. That is, until 1992. The model for this statue was made in my hometown, but here I sit again in my country, sitting, thinking, thoughts like birds, becoming words.”

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, UNION SQUARE PARK | In a leafy part of the park, a voice beckons, “Friend, come closer.”

Abraham Lincoln explains how many times he visited New York City: six, and only once as president. But besides his speechifying at the Cooper Union, the 16th president of the United States wonders, “How fares the Union? Is the country a place where one’s labors are fairly rewarded? May a citizen, striving, be made, by that process, a more dignified, spacious being? Is it a fair place, a free place? A generous place?”

He continues, “Have we attained that for which we so mightily strove? Do we walk peaceably together, finally, black and white, all traces of the previous cruel inequity eradicated, true equals at last?”

George Saunders, most recently author of “Lincoln in the Bardo,” imagined what Lincoln would say to us if he could, ending the monologue performed by Pete Simpson, with: “Well. It is humans down here, after all, so perhaps our work has not yet been perfectly accomplished. But I trust that, if not done, it is at least still being done. And that you are doing your part.”

MOHANDAS GANDHI, UNION SQUARE PARK | It is fitting that the statue of Mohandas Gandhi resides in Union Square Park — the starting point for so many protests and parades.

On the other side of the park from Lincoln where there is nowhere to hid from the sun’s power, Gandhi’s statue seems to be strolling in a field. Amid the bustle and crowd of the Union Square Greenmarket, he said he thinks he “would have liked it here, a city that respects all races and religions, and where nobody gives you a second glance — regardless what you look like.”

Thrity Umrigar pictured what Gandhi, who fought for India’s independence from the British through non-violent measures, would say about his legacy in a piece performed by Avinash Muddappa: “I was shot to death a few months after independence. But my dream of non-violence lives on. Martin Luther King Jr. adopted it in America to earn justice for blacks. Mandela freed South Africans through non-violence. I may have never traveled the world. But the world came to me.”

THE IMMIGRANTS, THE BATTERY | In The Battery (once known as Battery Park) tourists jostle for space to board boats to jet to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. It is apt, then, that a statue called the Immigrants — depicting several of them — is situated near these powerful symbols.

Written by Acito, the piece for the Immigrants is more like a short play than a monologue and is performed by actors Dan Sheynin and Alanah Rafferty.

The man in the front of the sculpture “with the beard on his face and the yarmulke on his head,” says, “I know, it looks like the crowd behind me is tryin’ to run me over, but if you stand at the side you’ll also see that the whole sculpture is sort of shaped like a ship, which I suppose makes me the Jewish equivalent of a mermaid on the prow. We look like a ship ‘cause that’s how we got to America.

Eight million of us were processed at Castle Garden between 1850 and 1890.”

The woman with the “wee baby, leanin’ against me husband,” says, “Generation after generation immigrants come to America, work hard for very little and still get blamed for all of society’s troubles. This sculpture reminds us that we’re all in the same boat.”

GIOVANNI DA VERRAZZANO, THE BATTERY | It is a name most New Yorkers are familiar with, albeit a bit different spelling: Verrazzano.

Inspired by Columbus, Giovanni da Verrazzano became an explorer that in 1524 “was the first European to sail into New York Bay. Yet, a century ago, I was forgotten, overshadowed by the exploits of Henry Hudson who arrived almost one hundred years after me. Some say he even used my maps!”

But Verrazzano does not lament for long in a monologue written by Joe Giordano and performed by Roberto Ragone. In 1909, an Italian newspaper in the city, Il Progresso, pushed for his statue, and in 1960 he “was further esteemed by the naming of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge that spans the New York boroughs of Brooklyn and Staten Island.”

(People also have the option to listen in Italian. Indeed, it was part of Talking Statues’ mission to have the statues “speak” in their native tongue as well.)

JOHN ERICSSON, THE BATTERY | Located on the outskirts of the park, John Ericsson’s statue proudly boasts one of the Swedish-American engineer’s invention. “Can you guess what I am holding in my left hand? It is a model of a warship that I … designed. I called my ship the Monitor, but people said it looked like a cheese box on a raft, which was a pretty good joke in 1861 when people still knew what a cheese box was.”

Acito wrote this monologue, which was performed by David Dencik, and can also be heard in Swedish.

The piece also explains what the picture on the statue’s pedestal is depicting — the Monitor “meeting the Virginia just outside Chesapeake Bay. This was the first battle in history between two armored ships, though I think the picture makes the gun turret look more like a hatbox. Which would also be a good joke if anyone knew what a hatbox was.”