BY JACKSON CHEN | Underfunded and struggling non-profits across New York that are reliant on municipal contracts are calling for a $25 million increase in city funding to cover the costs of things like rising rent, equipment purchases, capital repairs, and more.

In contracts with non-profits, costs outside paying staffers their salary are categorized as “other than personnel services,” or OTPS. The broad category can include expenses like employee health insurance, technology upgrades, or even meals and transportation for their clients.

As the cost components of OTPS continually rise and the city contract allowance for that swath of expenses remains flat, non-profit organizations feel the pinch. They are now asking for a 2.5 percent increase in the OTPS budget line item to stave off the necessity of cutting staff and programming to make up for the inevitable deficits.

In the public’s eye, neighborhood non-profits providing human services may seem to be doing just fine. The reality for many, however, is that they struggle to keep their heads above water.

“Organizations like ours work very hard to stretch every dollar,” said Greg Morris, the executive director of the Stanley Isaacs Center. “OTPS is not something people think about when they donate to people like us, but the reality is I got to keep the lights on, keep the rent paid, and make sure everyone’s got new supplies and resources.”

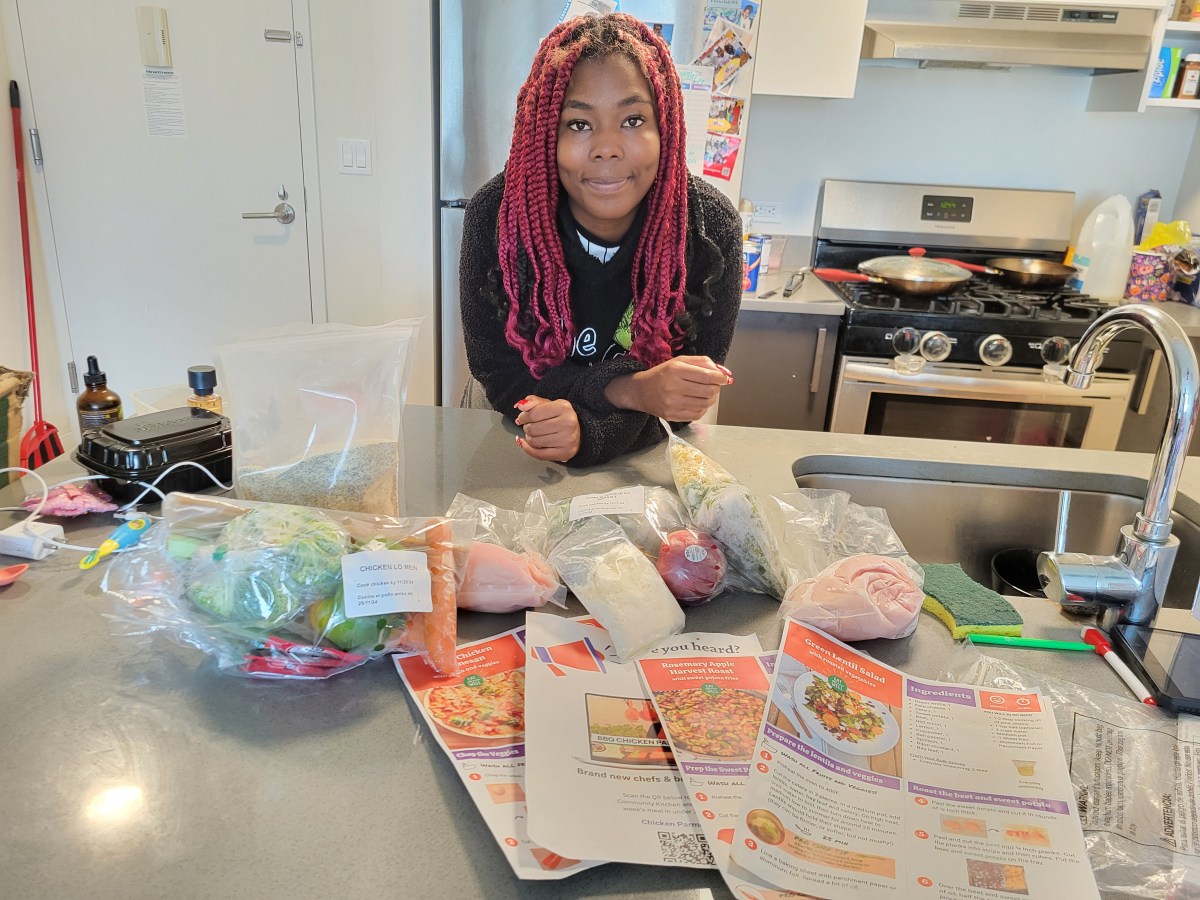

The multi-services center, located in one of the New York City House Authority’s campuses at East 92nd Street and First Avenue, has been open since 1964. Over the years, the Isaacs Center has provided their seniors and youth with places to gather and programming, while also running the Meals on Wheels program for a delivery area that runs from East 59th Street to East 142nd Street on the East Side.

Like many other non-profits focused on providing community services, its attention to its own sustainability is often kicked down the road, despite undeniable deterioration in the resources at hand.

Morris explained that his staff has never received raises and the center hasn’t had the opportunity to focus on research and development to see how to better provide their services.

“When we don’t have the dollars to provide the professional development that we would like to provide,” Morris said, “you end up having to cut corners.”

On the West Side, the financial constraints facing the Goddard Riverside Community Center, at Columbus Avenue and West 88th Street, has forced it to pass along health insurance cost increases to its employees, according to Stephan Russo, the center’s executive director.

Russo explained that Goddard Riverside — which offers a broad array of childhood, youth, senior, housing, and legal services — participates in the highly competitive process of applying for multi-year government contracts. With a track record dating back to its founding in 1959, he said, the center brings strong credentials and credibility to its applications. Still, the contracts it receives often don’t fully cover its OTPS costs, leaving it scrambling to bridge the gap.

“Sometimes we then have to increase the cost that we put on employees,” Russo said. “Or have to try and raise private money to make up that difference.”

Russo explained that in rough terms, Goddard Riverside relies on city contracts for about 75 percent of its budget, with the remainder coming from private donors.

Raising money specifically to cover OTPS expenses, he said, is not a particularly attractive draw for those interested in supporting the work of non-profits.

“I understand it’s a hard sell sometimes, given the additional money isn’t technically going to feed more people,” Russo said. “But we can’t do those services without a strong organization.”

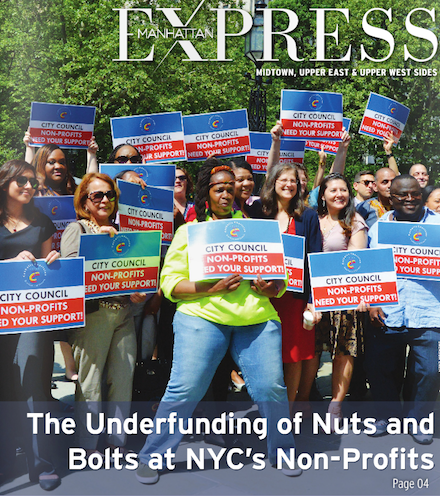

With worsening financial situations, non-profits have banded together under the guidance of West Side City Councilmember Helen Rosenthal and the Human Services Council — an umbrella organization that represents non-profits — and they held a rally on May 26 to grab the mayor’s attention.

According to Allison Sesso, the executive director of the Human Services Council, the city is spending almost $5 billion dollars on these human services, which she argued are on the “brink of disaster.”

“We as organizations are living payroll to payroll,” Sesso said. “Just like the clients we’re serving are living paycheck to paycheck and we have to stop that.”

The city hasn’t been completely deaf to the cries of the non-profits. Mayor Bill de Blasio’s pledge to increase the minimum wage of government employees to $15 an hour by the end of 2018 would extend to those working under city contracts.

“The de Blasio administration is committed to the city’s non-profit sector and the vulnerable residents it serves,” said Freddi Goldstein, a spokesperson for the mayor’s office. “We are always looking for ways to strengthen non-profits and will continue to do so moving forward.”

Goldstein did not address the specifics of the proposed OTPS increase, but noted that the administration and the Council are still at work on next year’s budget.

The call to action has already won support from 49 councilmembers, according to Rosenthal, who chairs the Council’s Contracts Committee.

According to the councilmember, non-profits that provide human services are often paid 80 cents for every dollar of work they actually provide, leaving them in precarious situations when it comes to OTPS costs. Rosenthal added that the city needs to realize the importance of non-profits in providing crucial services for the city.

“If the city wants to build infrastructure, the city puts in money in the budget for that and if costs go over, we put in more money,” Rosenthal said, referring to capital spending. “That’s what we have to start doing for our human services contracts as well .”