By Ed Gold

I’m not sure when I found out that Marvin Korman had written his affectionate, easy-to-read, colorful and humorous memoir about his youthful years in the borough to the north.

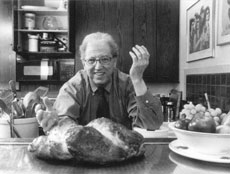

We were chatting at a Village event when he mentioned that his first book, “In My Father’s Bakery: A Bronx Memoir,” was going to be published in October. When he learned that I also came from the Bronx, and that I occasionally wrote for The Villager, he told me he was sending bound galleys to me.

My first reaction about a book about the Bronx brought to mind Ogden Nash’s famous short poem:

The Bronx.

No Thonx.

But Korman, who has lived in Greenwich Village for more than 25 years, has given life to the Bronx experience with particular focus on the folkways of Jewish and ethnic happenings in the East Tremont neighborhood where his father, Nathan, ran the family bakery.

Young Korman would do his homework in the rear of the shop and later helped out in sales amid the prune Danish, eclairs, napoleons, apple crumb pies and jelly donuts.

The dominant character in this loving, nostalgic short-story collection is Korman’s father, a no-nonsense, street-smart entrepreneur, who likes his cigars, his scotch, pinochle and the racetrack, while he loves his bakery and his family.

Nathan has a way with words. When a suspicious fire shuts down his bakery and he’s told it will take six weeks to repair, he bristles: “What do you think they’re building, Grand Central Station!” When he discovers that a vegetable storeowner is a womanizer, he suggests: “If he likes to squeeze, let him squeeze his tomatoes.”

The elder Korman always retains his cool. He tries to have good labor relations because in his neighborhood in the ’30s and early ’40s crossing a picket line was considered sinful. The bakers and sales help each had their own unions and Nathan felt two were enough. When he found out there was a union for bagel-makers, he stopped making bagels and bought them at wholesale.

At that period in time the Communists were strong in his neighborhood and the head red decided to make a name for himself. He said he would set up a picket line outside the bakery unless the price of bread was reduced from 10 cents to eight cents a pound. But Nathan cleverly outfoxed him in one of the book’s most satisfying tales.

The memoir is filled with other distinctive characters including Uncle Maxie, a shy, gentle childlike relative who almost never speaks up. He takes the author, then in his teens, to Yankee Stadium to see the great hitter, Hank Greenberg, of the visiting Detroit Tigers, and a hero in the Jewish community. Nearby is a bigot who lets it all hang out against Greenberg. As Maxie and his entourage leave the Stadium, Maxie turns on the bigot and tells him where to get off, to Korman’s pleasant surprise.

There’s always something happening in the East Tremont neighborhood. A Protestant minister is called on to give last rites to a fallen bakery worker who is Catholic, and who, it turns out, is not dead at all.

There’s Izzy, the bookie, who uses the bakery as his office, uses the phone to lay off bets, sometimes gets into hot water, and pays back Nathan by serving as his chauffeur.

There’s Amelia, the housekeeper for two of Korman’s single uncles and his grandfather. The family is shaken up when she reveals she’s pregnant. Who’s the father? Is it one of the relatives? Lots of palpitations before the issue is resolved.

Possibly the most bizarre story involves a band of Gypsies who apparently specialize in repairing the large copper bowls used at the bakery. Nathan and the Gypsies can’t agree on a price so they make a deal permitting the Gypsies, preparing for a celebration, to roast their holiday lamb in the bakery oven after which the Gypsies dance and sing on the bakery premises for hours. And it’s just before Passover.

Korman remembers his genius cousin from Riverdale — “just below Yonkers,” Nathan says with a touch of malice. The cousin turns out to be gay, has a short marriage with a lesbian and winds up selling antiques.

There are also occasional lawsuits against the bakery, some rather ugly, but a few with charm, like the discovery of a wedding ring in the challah bread.

The East Tremont neighborhood changed dramatically after World War II and in the ’60s a Passover celebration was held in the local Y.M.H.A./Y.W.H.A. for 70 kids, mostly black and Hispanic. Korman’s mother, Lilly, insisted on making the gefilte fish, and the children loved it, particularly after pouring ketchup over the holiday dish.

Lilly learned an important lesson during that period. Many Jewish people of her generation used the term “schwartzer” to describe black people, not recognizing its demeaning connotation, and despite the proddings from her son. But in preparing for the seder she had worked closely with a black woman who became a perfect kitchen partner. The two developed a friendship and Lilly never used the derogatory term again.

While Korman in the early ’40s was working on bakery customers, I was not far away working for an eccentric jeweler who dealt in desk sets and diamonds, bought old gold and silver and served as a conduit for hot watches. But my experiences were mundane compared to Korman’s who makes his Bronx amusing, exciting and poignant.

His writing skills were honed over many years as vice president for advertising and promotion at Columbia Pictures and NBC Television. He’ll be holding reading and signing sessions in and out of New York, from Boston to Philadelphia, with a stop in our neighborhood at Teachers and Writers Collaborative, 5 Union Sq., on Oct. 17 at 7:30 p.m.

He’s also likely to be at the annual Caring Community bash next month; his wife Eleanore, to whom the book is dedicated, is chairperson of that organization’s board of directors.

“In My Father’s Bakery: A Bronx Memoir,” by Marvin Korman, 202 pp., hardcover, Red Rock Press, $22.