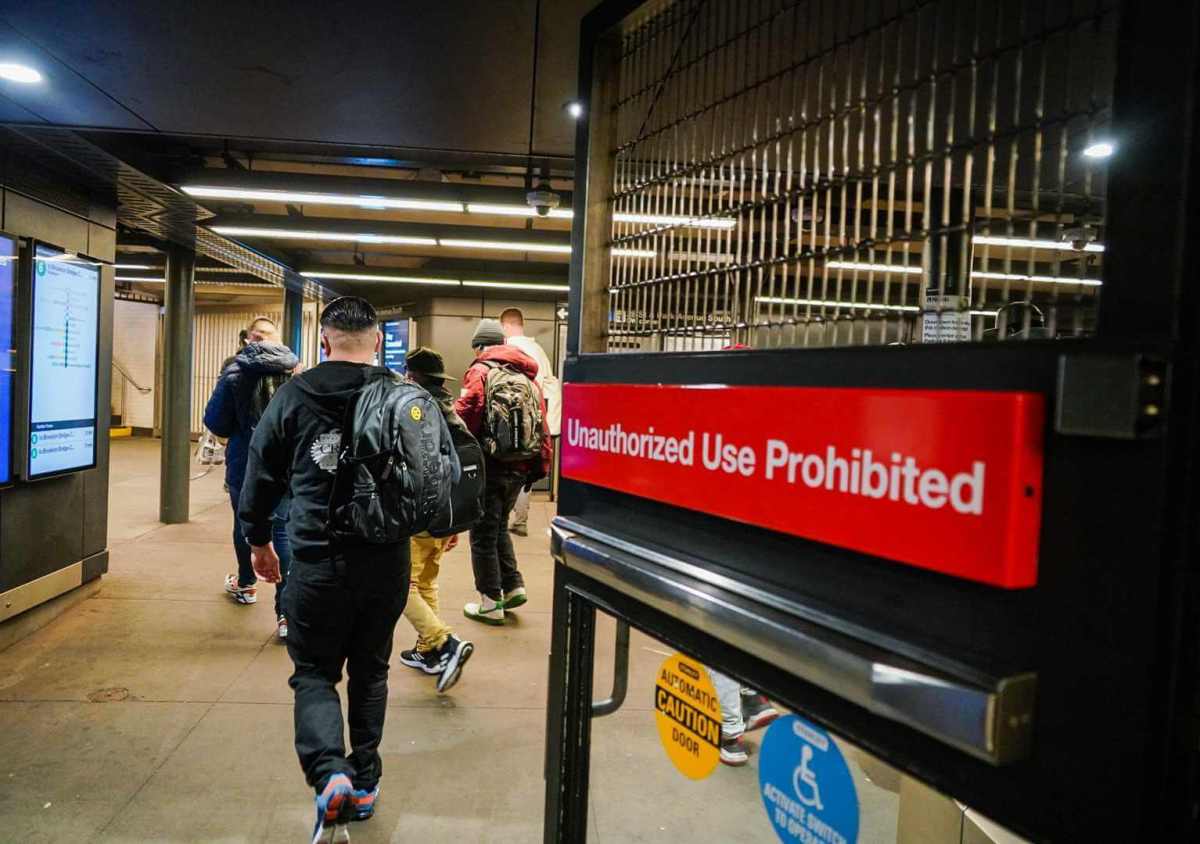

The MTA wants to re-examine its emergency exit gates in subway stations amid its renewed focus on curbing fare evasion, agency chief Janno Lieber said Wednesday.

“There’s no question that those emergency exit gates, which are an attempt to comply with the fire code — so God forbid people can get out in a fire emergency — that design has not worked, because it’s become a superhighway for fare evasion, honestly,” Lieber said during a May 4 appearance on the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC.

“A lot of the riders who want to play by the rules are feeling like they’re suckers because they’re paying the fare and they see people sail right past them through the emergency gates,” he added.

The chair and CEO of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority added that his recently-convened commission on fare evasion will look at how to comply with fire codes without leaving an easy way for people to not pay $2.75.

“One of the principal things that this panel is going to look at is are there different designs for the fare gates — maybe it’ll be floor to ceiling … but especially this exiting requirement. How do we comply with the fire code without creating something that’s going to be an open door,” said Lieber.

The transit big last week assembled the 12-member “blue ribbon” panel to study fare evasion on the subways and buses, along with uncollected tickets on its two commuter railroads, and toll dodgers on the Authority’s seven bridges and two tunnels.

The MTA estimates that all those unpaid fares and tolls will cost the agency more than $500 million this year based on current rates, Lieber said.

His recent push comes after years of MTA leaders and politicians beating the drum about fare evasion, and former Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2019 also took aim at redesigning the fare gates.

In 2005 and 2006, the MTA expanded the quick exits by modifying some 1,500 locked access gates in its system to allow riders to get out easily during emergencies by pushing a so-called “panic bar.”

The move was reportedly lobbied for by pols after the 2005 bombings of the London Underground.

The gates let off a piercing alarm anytime someone opened them, until MTA turned off the screeching noise in 2014 — only to turn it back on as an NYPD-requested pilot project in 2019 at 10 stations to see if the racket would deter fare evasion.

“There are a lot of people who contend that as soon as the alarm came off the gates, fare evasion increased,” said Lisa Daglian, the executive director of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA, an in-house rider advocacy group.

The issue of locked emergency gates resurfaced on social media recently, when a rider posted about a shut exit at the Vernon Boulevard-Jackson Avenue station in Long Island City, Queens, on April 16.

As part of the crackdown on fare evasion, more emergency exits in NYC subways are locked. This is wrong and dangerous for countless reasons. Also a person on my train couldn’t get their baby stroller out. I tried helping them lift it over the turnstiles but it wouldn’t fit. 🤬 pic.twitter.com/Zp0cXH0sFF

— Jared Chausow – Go to bit.ly/ParoleJusticeAction (@jchausow) April 16, 2022

The viral post came just days after the mass shooting on a subway train in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, on April 12, when 10 straphangers were shot and riders ran for their lives out of blood-stained trains and platforms.

The tweet spawned several other reports of locked emergency gates from riders, such as 161st Street-Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, 86th Street station at Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, and Franklin Avenue and Utica Avenue stations in Brooklyn.

The New York City Transit Subway Twitter account responded to some saying the gates were “malfunctioning,” adding that the agency only locks the gates for long-term construction work.

Hello, Jenn. That gate was malfunctioning: We don't lock emergency gates unless there is long-term construction work.

This problem was fixed by our team yesterday, and the gate is working again. ^TS

— NYCT Subway (@NYCTSubway) April 18, 2022

An agency spokesperson said MTA does not lock the gates if the stations are open to the public.

“NYC Transit does not deliberately lock emergency gates to deter fare evasion or for any other reason in stations that are open to the public,” said Sean Butler in an email. “When vandalism or other issues necessitate maintenance and repairs, those are ordered expeditiously.”

The full-size gates also are also essential access for people using wheelchairs, parents with strollers, or commuters carrying large objects that are hard to get through the turnstiles, noted Daglian.

She also recently saw an emergency gate at the Vernon Boulevard-Jackson Avenue stop out of order, the same stop of the viral tweet two weeks ago.

“I saw people lifting their kids’ strollers over the turnstiles, trying to get out with heavy packages and bulky packages,” she said.

“It’s important that they work and be functional,” Daglian continued. “God forbid there’s a fire, you want to have as many egress points as possible and having a locked exit is akin to locking all the doors in a house and not being able to get out.”