When the coronavirus pandemic first gripped New York City last year, the grocery store became the sole destination for many New Yorkers shut up at home during the lockdown. Many saw prices increase as shoppers cleared out store’s stock of the essentials — bread, eggs, and, of course, toilet paper.

When lockdowns eased and things started to return to “normal,” so did the amount of paper goods and milk on the shelves. The price of those goods, however, hasn’t. Supply chain slowdowns and labor shortages brought on by the pandemic have caused inflation rates in the U.S. to soar to their highest in 40 years, and the weekly trip to the grocery store has only gotten more painful over the last year.

Nationwide, the Consumer Price Index, which measures the price of goods typically purchased by American households, shows that the cost of “food at home” has risen 7.4 percent since January 2021.

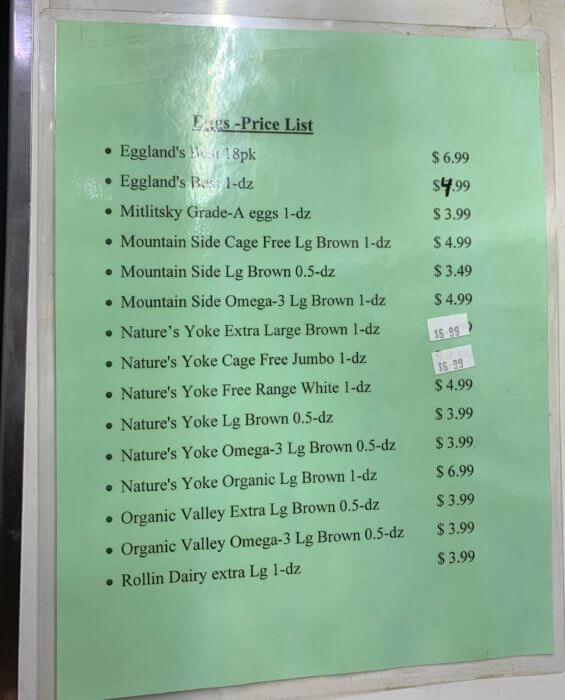

Closer to home, prices were even higher — in the New York, Newark, and Jersey City area, the price of groceries rose 1.2 percent in January and 7.6 percent in the last year, with the cost of meat, poultry, fish and eggs up 16 percent compared to this time last year. The dramatic increase has some shoppers setting their usual staples back on the shelves.

On a quiet afternoon at the NYC Fresh Market supermarket on Myrtle Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn, Tonya Trossi and Raymond Rebollo sorted through packs of chicken breasts, exclaiming at the prices.

“It’s inflation!” Rebollo remarked, as the pair put another package back down on the shelf.

Grocery shopping for their family of four has become more difficult as the cost of food — especially meat — has skyrocketed, Trossi said.

“One thing that we noticed is that sometimes the meat’s not as fresh as it used to be, Rebello said. “We have to look more in different locations to try to get some. But the prices doesn’t change whether the meat is good or bad, it’s still the same.”

Fresh Market was their second supermarket of the day. At the first, a Bravo Supermarket nearby, the chicken they needed was more than $9, and had expired two days before, Trossi said. At Fresh Market, 2.41 lbs of chicken breasts — a pack of three — was a whopping $15.16, and just over a pound of ground beef sold for nearly $12.

While the price of meat seemed to have risen the most, the Trossi and Rebello have also balked at the price of rice and cooking oil, and have started getting everything they can in bulk at BJ’s.

“Everything went up,” Rebello said. “Clothes, sneakers, everything, you name it, it’s not just food. But it hurts more when it’s food, because you’re trying to get the good value like you used to. You’ve got to adapt to it, or you’re going to starve.”

Since the 2008 financial crisis, inflation has been well below the norm of the 2 percent annual increase targeted by the Federal Reserve Bank, even though 3 to 5 percent per year was considered generally acceptable prior to that point, said Merih Uctum, economics professor at Brooklyn College, via email.

Anything above 5 percent is worrying to policymakers, Uctum said.

The current spike is driven by myriad factors, she said. During the worst of the pandemic, demand shifted from services — things like movies and restaurants — to goods, like home improvement equipment and cars. At the same time, suppliers were forced to cut their production because of lockdowns. When production started back up again, issues with the supply chain pushed the price of shipment up, and companies passed that cost on to consumers, raising the already higher-than-average prices. Ongoing labor shortages and low interest rates have also pushed prices higher.

Prices for food and oil have risen the most notably, she said. Demand for oil as lockdowns have eased and Americans started traveling again has increased, and continued supply chain issues have driven up the cost of food.

Generally, inflation alone shouldn’t be a marked strain on the everyday consumer’s budget, Uctum said.

“In reality, as long as wages are indexed to inflation, i.e. they increase at the same rate, the buying power should not be hurt,” she said. “The problem starts arising if inflationary expectations become entrenched, meaning people start increasing wages and other prices more than the actual inflation rate, expecting it to be higher. Then we start seeing prices spiraling up.”

According to the most recently available data, in the second quarter of 2021, wages in Kings County had decreased just under one percent from the year before. The average Brooklynite is taking home $1,099 per week or less, the lowest of any of the five boroughs.

It’s not clear yet whether those “inflationary expectations,” when businesses raise their prices in anticipation of higher inflation, are contributing to the current spike in the price of food, Uctum said.

“It’s just anecdotal evidence that I’ve seen in the grocery store when I go for milk or something like that, it’s an incredible increase in prices,” she said. “The milk carton going from $5 to $7, and there’s absolutely no justification for such a huge increase. So I think we are also seeing some expectation embedded into this change in prices.”

In an effort to tamp down on inflation, the Federal Reserve is expected to increase interest rates starting this month. Higher interest rates decrease spending, slow down the economy, and reduce inflation. Since companies will expect lower inflation rates, the move might also cut down on the “inflationary expectations,” when companies raise their prices higher than the actual inflation rate.

Mike Hyler, a retail manager for Wilklow Orchards who was running the farm’s outdoor market at Brooklyn Borough Hall this week, said the company hasn’t yet raised their prices this year, but it seems inevitable that they will.

Everything from diesel to the plastic bags customers use to carry fresh produce has gotten more expensive. “Pretty much every aspect of our business” costs more than it used to, he said, and there’s not much to do other than charge customers more.

Some of the factors pushing prices higher are temporary, and will subside with time, Uctum said. Consumer demand will shift back to services, lowering demand on goods and taking pressure off the broken supply chain. The war in Ukraine will probably raise the price of oil and negatively impact the supply chain, since Russia is a major source of oil and gas.

“On the other hand, as usual in an international crisis, capital is fleeing risky regions in the world and investors are purchasing US assets since the U.S. dollar is considered to be a safe asset,” she said. “The resulting appreciation of the currency also reduces imported goods prices, and therefore will most likely moderate inflation. Which of these factors dominate remains to be seen.”

In the meantime, Brooklynites will continue to scrap and save where they can as long as prices continue to climb.

Right now, Trossi is out of work while she takes care of her own health and her son, so Rebello is the sole source of income for their household.

“We’re trying to survive, that’s all you can do, day by day, that’s all you can do,” he said.

A version of this story ran on amNewYork as part of a series examining the impact of inflation on the working New Yorker and local businesses, titled “Everything is Too Damn High.”