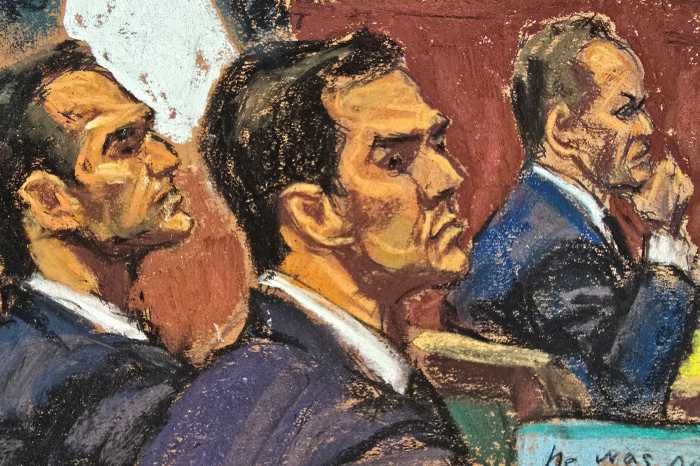

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg and New York City prosecutors have asked the United States Supreme Court to reinstate the conviction of Pedro Hernandez, the man who was found guilty in 2017 of murdering and kidnapping six-year-old Etan Patz in 1979.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit overturned Hernandez’s conviction in July, with a three-judge panel finding that New York Supreme Court Judge Maxwell Wiley, who presided over Hernandez’s trial, incorrectly answered a question from the jury regarding what evidence they could consider when making their decision.

Hernandez, now 64, repeatedly confessed to police that he had kidnapped Patz while he was walking to his New York City bus stop and killed him in a SoHo basement, but Hernandez’s lawyers have argued that his confession was the product of psychotic delusion — and that his first confession before police came before he was told he had the right to remain silent.

During 2017 jury deliberations, Wiley told jurors that, even if they decided Hernandez didn’t initially voluntarily confess before he’d been read his rights, they didn’t need to disregard his other subsequent confessions to police, or his statements to members of the public, like his family and friends, whom he told he’d “done a bad thing and killed a child in New York,” according to police reports.

The Second Circuit disagreed, ruling that the jury should have received a fuller answer as to how federal case law requires confessions like Hernandez’s to be considered.

According to the 2004 Supreme Court ruling in Missouri v. Seibert, when police make a conscious choice to question a suspect first and get a confession, then read that suspect their rights and get the suspect to repeat their confession, neither confession should be considered as evidence, unless sufficient “curative measures” were taken.

However, the court has also ruled that as long as police didn’t intentionally refrain from reading a suspect their rights before a confession, a second confession after their rights are read is admissible.

The appellate judges said Wiley’s instruction ran afoul of the Seibert ruling because it wasn’t explanatory enough.

“Because of the lack of physical evidence, the trial—Hernandez’s second, after the first jury hung—hinged entirely on Hernandez’s purported confessions to the crime. Central to the trial was whether Hernandez’s confessions to law enforcement were made voluntarily, knowingly, and intelligently,” the appeals court wrote in July. “The jury was not told that it could disregard those statements, or on what basis it might even be obligated to disregard them.”

Bragg, who announced a few weeks ago that he’d be retrying Hernandez’s case since his conviction was overturned, argued that Hernandez’s conviction should be reinstated because the federal court’s invalidation of a state jury verdict “flouted” a law that limits when a federal court can overturn state court convictions.

“The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit…ruling was not based on any error in the decades-long investigation, in the admission of Hernandez’s confessions, or in the evidence presented at trial. Instead, the Second Circuit undid the conviction based on the purported inadequacy of the state trial court’s response to a single jury note,” Bragg’s filing says. “The court of appeals’ ruling ‘plainly violated Congress’s prohibition on disturbing state-court judgments on federal habeas review absent an error that lies beyond any possibility for fairminded disagreement.’”

The filing, which Bragg submitted with appeals division chief Steven Wu and federal habeas corpus unit chief Stephen Kress to the Supreme Court Thursday, also argues that Hernandez’s confessions included “critical details he could not have known unless he were the perpetrator,” and that the trial was thorough, as it stretched for five months and included 66 witnesses.

Harvey Fishbein, one of Hernandez’s attorneys, did not immediately respond to a request for comment. He’s previously said that the appeals court didn’t reverse his client’s conviction purely on a technical violation.

He has called the conviction “fundamentally flawed” and emphasized that the appeals court judges said that they had “grave doubts” about the validity of the confessions.

It’s been argued that Hernandez fits the profile of someone who could be prone to making false confessions and that not all of his statements matched facts of the case. Doctors have diagnosed Hernandez with a myriad of disorders, including psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, chronic mental illness and memory impairment, along with an incredibly low IQ that would mean he was “functioning at the lowest level of intelligence compared to other people,” court filings say.

His attorneys argued that his conditions made him “especially susceptible to confessionary hallucinations.”

When Hernandez was first questioned by police, he asked to leave multiple times, accused the officers of “trying to pin what happened to that boy on [him],” spoke about seeing ghosts, seemed to not completely understand his right to an attorney and asked detectives how to spell the word “choke” when writing his confession on paper, court filings show. Whether his confession was accurate, voluntary and admissible evidence was a central point of his trial.

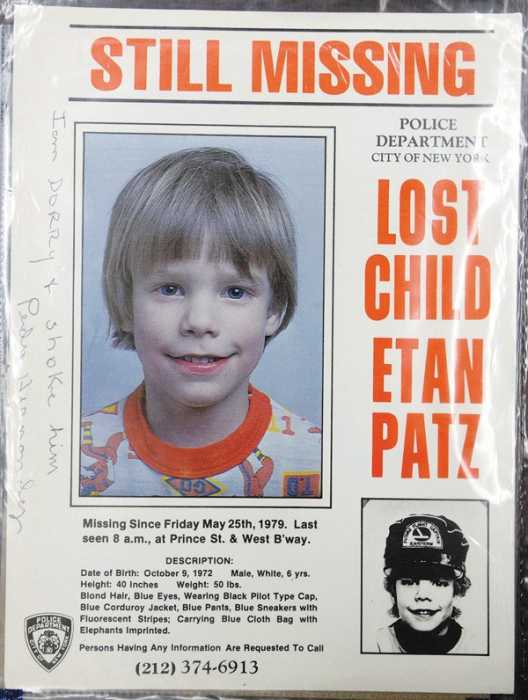

Patz’s disappearance drew national attention when his face was plastered across milk cartons during his search and police and prosecutors hit repeated dead ends, like never finding his body or any physical evidence of his disappearance that could be tied to anyone.

Now more than four decades old, it has been considered one of the country’s most confusing cases; a number of suspects over the years have confessed to molesting and abusing other children — but each one denied kidnapping and killing Patz.

One notable suspect was Jose Ramos, the boyfriend of Patz’s babysitter, who was arrested in 1982 after trying to lure two boys to a drainpipe. Police discovered several photographs of young boys in Ramos’s personal property, including one that resembled Patz. In 1987, Ramos was convicted of indecent assault of a five-year-old boy and sentenced to three and a half to seven years in prison.

Patz’s babysitter’s son said Ramos had molested him, and in 1990, Ramos admitted to molesting another eight-year-old boy on more than one occasion and was sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison. In 1991, Ramos confessed to taking a young boy from Washington Square Park to his apartment, molesting him, and putting him on the subway on the same day as Patz’s disappearance. He couldn’t confirm whether the boy was Patz, but said that even if it was, he didn’t kill him.

Another suspect in the case was Othniel Miller, a carpenter who had done work in Patz’s family’s apartment and had a basement workshop between the apartment and the bus stop. Miller said Patz had been in his basement workshop the night before, helping him with carpentry in exchange for a dollar. A police dog trained to detect the odor of human decomposition picked up that scent in Miller’s basement, but a dig excavating his workshop didn’t turn up anything. Miller admitted to having sexual intercourse with a girl who was approximately ten years old in 1979, but never admitted any connection to Patz’s disappearance and was never charged in his case.

Hernandez, meanwhile, ran a bodega on the route Patz would walk to school. He was not a suspect until 2012, when his brother-in-law alerted the police to statements Hernandez was making about abusing and killing a child in New York City, after reading about the case in the news when Miller was identified as a suspect. The statements varied widely, from Hernandez saying he “sodomized” a child to him saying he “stabbed” a child with a “pointy stick” or strangled a kid after a child threw a ball at him.

Hernandez received a sentence of 25 years to life. He remains in custody in a New York State prison.