By Julie Shapiro

:

Families still waiting for answers as they grieve

Joseph Graffagnino Sr. never spoke with his son about the dangers of firefighting.

They talked about how much Joseph Graffagnino Jr. loved his job at the Engine 24/Ladder 5 firehouse, and they laughed over the practical jokes the firefighters played on each other — but they never spoke about the mazes of burning buildings, the dark billowing smoke, the oxygen tanks that run out of air.

“You try to block that out of your head,” the elder Graffagnino said in an interview last week. “You don’t want to think about that. You’re always afraid of the phone call in the middle of the night.”

As it turned out, the phone call came during the day, when the father was at church.

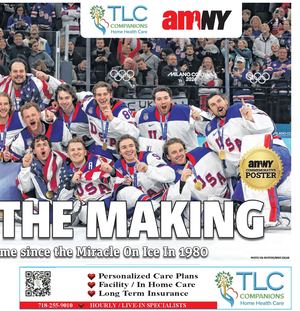

It was one year ago, Sat., Aug. 18, 2007, and the Deutsche Bank building across from the World Trade Center site was in flames. More than 270 firefighters responded to the asbestos-contaminated building, which was damaged on 9/11 and was in the process of being cleaned and demolished.

Where firefighters expected staircases, they found plywood barriers. Where they looked for windows, they found plastic sheeting. And at the standpipe, where they expected torrents of water to battle the blaze, they found not even a trickle, because the standpipe was broken and it had not been inspected.

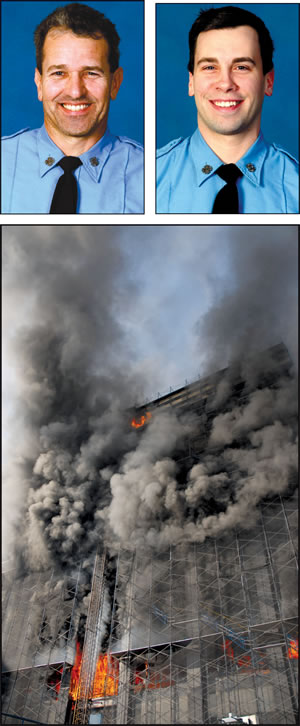

Firefighters Graffagnino Jr., 33, and Robert Beddia, 53, died of cardiac arrest when their oxygen tanks ran out, leaving them only carbon monoxide to breathe. Graffagnino left behind his parents, wife, 4-year-old daughter and infant son. Beddia was divorced and left behind two older brothers and two younger sisters.

For Graffagnino Sr., 60, the approach of the one-year anniversary of his son’s death stirs memories and emotions that had not yet settled.

“I just want to get it over with,” Graffagnino said. “The wound is always open…. It never really goes away.”

His son’s death thrust Graffagnino into the spotlight. While at first the cameras and microphones just added to the surreal blur following the fire, Graffagnino soon began using his platform to advocate for firefighters’ safety. He successfully fought for changes to the city building code, and at his urging, the Fire Department is testing a new technology that will help commanders find firefighters who are trapped in burning buildings.

“I’m tying to make a positive out of a negative,” Graffagnino said. “[But] I don’t know why it takes a national calamity to get people off their ass.”

The deadly fire came after years of Community Board 1 and other local residents and activists warning that the building was unsafe. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, which owns the building, hired an asbestos decontamination subcontractor who had no experience and alleged mob ties. A series of accidents led up to the fire, and each time the community raised an alarm. Each time, they were ignored.

In the year since the fire, abatement work at the building has resumed under a new subcontractor and much stricter oversight, but demolition work is not expected to start until early next year. In response to residents’ confusion and fear on the day of the fire, the city launched a widely hailed emergency notification system. But community members still want more transparency from the L.M.D.C., especially regarding the chain of command.

Mourning the fallen

In the Engine 24/Ladder 5 firehouse on Sixth Ave. at W. Houston St., the one-year anniversary of the fire is a time to remember something that no one had forgotten.

“They’re gearing up for it and girding themselves for it,” said Victoria Grantham, whose fiance is a firefighter there. The planned memorial events are a good time for reflection, Grantham said, “but they’re also a real reminder.”

The firehouse is no stranger to loss. Eleven of the house’s firefighters were killed on 9/11, and the losses are magnified by the fact that firefighters aren’t like ordinary co-workers.

“We’re a band of brothers,” said Ken Fulcher, 39, who has been with the Engine 24/Ladder 5 firehouse for 10 years. He responded to the Deutsche Bank fire alongside Graffagnino and Beddia.

“There’s no way to describe what it’s like,” Fulcher said this week in a telephone interview. “It’s very sad…. You think about it every day.”

At the same time, Fulcher said, the firefighters have to move forward and take care of their families.

“We do what Bobby and Joey would want us to do: We hold our heads high and work,” Fulcher said. “They’re looking down on us, smiling, knowing we’re still going to work.”

Bobby Beddia was the leader, the senior man in the firehouse. The firefighters called him the “pope of the Village” because he knew all the good restaurants and bars, Fulcher said. As a bartender at Chumley’s in the West Village, Beddia taught new firefighters the ropes of bartending. He was a quick-witted Texas hold ‘em player and an avid golfer.

Barbara Crocco, Beddia’s sister, described him as “the typical big brother, always the protector.” Beddia was the one who started up games of kickball and volleyball with his troop of nieces and nephews, and he was the first grownup to jump in the pool with them. He loved kids but had none of his own.

“He always made everyone around him feel good,” Crocco said.

Beddia also was a charming flirt who in the last year of his life would answer people with a riddle when they asked how old he was. He’d respond that he was in the year of his birth, meaning that his age, 53, matched the year he was born, 1953. A mathematician who heard about Beddia’s pickup line later crafted the Beddia Theorem to describe the relationship Beddia noticed.

Beddia responded to ground zero on 9/11, and afterwards he seemed more serious, less carefree, Crocco said.

One day shortly after 9/11, a woman Beddia had never met stopped by the firehouse, looked in and just started crying. Beddia put his arm around her and said, “Hey, wait a minute, you’re supposed to be the one comforting me,” Crocco said. The woman laughed, and she and Beddia became friends.

When Beddia joined the Fire Department in 1983, Crocco used to call his firehouse whenever she saw a big fire on the news, just to make sure he was okay. He told her she was being silly, and she eventually stopped. Now, Crocco, 50, can barely speak about him without crying.

“This week is going to be really tough,” she said.

Joey Graffagnino was a happy-go-lucky guy who was the life of the party and had a penchant for playing practical jokes, said Fulcher, his firefighter friend. Graffagnino tended bar at the Salty Dog in Bay Ridge and was a bodybuilder who won the title Mr. Ft. Hamilton.

“Joey always had a smile on his face, and he could always bring a smile to someone’s face,” Fulcher said.

When it snowed, Graffagnino Sr. said his son trekked to the grocery store for the old women who lived on his block, and he shoveled out the neighbors’ cars. He wanted to be a firefighter from the time he was a little boy. He spent six years on the waiting list before being accepted.

“He was very uplifting, very spontaneous,” Graffagnino Sr. said. “He would be the light in the room. When [he’s] gone, it’s a huge void. You can’t fill that void.”

Graffagnino Sr. has a similar uplifting effect on people, greeting them with a smile that is easy to return. And even when speaking of his son, the memories are not all sad.

“He liked to cook, and I like to eat,” Graffagnino joked recently. “It worked out good.”

Beddia and Graffagnino were both good cooks, especially Italian food, Fulcher said, but Graffagnino had one quirk when it came to sampling food the other firefighters cooked.

“Joey would only eat his mother’s meatballs,” Fulcher said. “He wouldn’t eat anyone else’s, not even his wife’s. That’s the type of guy he was.”

Joe Hund, a Brooklyn firefighter and close friend of Graffagnino Jr., called him “the nicest guy in the world.”

On 9/11, Hund fought the fire that burned in the basement and ground floor of the Deutsche Bank building.

“I knew that day it had to come down,” he said. “I lost a good friend in that building seven years later.”

Placing Blame Graffagnino Sr. places the bulk of the responsibility for last August’s fire on the L.M.D.C. He is suing them, along with the city, Department of Buildings, Fire Department, contractor Bovis Lend Lease and subcontractor John Galt Corp. Beddia’s family filed a similar civil suit. Both suits are on hold while the district attorney investigates criminal charges. Graffagnino said the district attorney was supposed to do indictments this summer but now pushed them to September or October. A source told Downtown Express that the grand jury has the month of August off and intends to wrap up the indictments when they return in September. Meanwhile, Graffagnino is getting impatient.

“People should go to jail for this,” Graffagnino said. “Hitting a millionaire with a fine is [B.S.]. You were [behind] this, you could have stopped it. You should pay.”

Crocco, Beddia’s sister, added that she doesn’t know if the indictments will make her feel any better, but it’s important to hold people accountable and punish them for what happened.

Alicia Maxey Greene, spokesperson for the D.A., would say only, “The investigation is continuing.”

The Uniformed Firefighters’ Association released a statement to Downtown Express saying they have full confidence in the D.A.’s investigation. The Uniformed Fire Officers Association released a similar statement saying Graffagnino and Beddia deserve a thorough investigation of what went wrong and who was at fault.

Community Board 1 passed a resolution several years ago warning the L.M.D.C. about John Galt Corp., but the L.M.D.C. ignored the warning. After the fire, C.B. 1 submitted the resolution to the D.A.’s office, hoping to make the case that the L.M.D.C. was negligent in hiring John Galt since the L.M.D.C. had reason to believe the subcontractor was unfit for the job, a senior C.B. 1 official said.

A source briefed on the D.A. investigation told Downtown Express last year that while the criminal investigation is taking precedence, the D.A. plans to release a report citing the non-criminal government mistakes that led to the fatal fire.

L.M.D.C. chairperson Avi Schick declined to comment for this story.

Graffagnino Sr. designs telecommunications systems for a living, and after the fire he decided to apply his work to communications between firefighters in a burning building and the commander back on the truck. Graffagnino invented the idea of computer chips that track firefighters, sending information about the firefighter’s location and the amount of oxygen left in his tank to the commander via radio waves. If the Fire Department can overlay that information on the Buildings Department’s digital blueprints of buildings, then the commander can guide firefighters toward exits from the safety of the truck.

Several firehouses in Queens and the Bronx are testing the radio wave technology, and Graffagnino said he’s gotten a positive response from the Fire Department.

“It definitely would have saved his life,” Graffagnino said of the new technology helping his son. “The first fireman that lives because of this, I want to be there.”

Julie@DowntownExpress.com