BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC | On the night of Sept. 17, 2016, a man exits Penn Station at W. 31st St. and Eighth Ave. with three bags. It is approximately 6:42 p.m. For about a minute, he pauses and sets two of the bags down. He then proceeds south on Eighth Ave.

Later, at about 6:51 p.m., video footage shows the same man with the same three bags stopping on W. 25th St. He puts the two bags — suitcases that can roll — next to a metal bench and sits for about 19 minutes. He again continues south on Eighth Ave.

He reaches W. 23rd St. between Sixth and Seventh Aves. Security footage from a nearby business shows him passing the shuttered St. Vincent de Paul Church, then turning around and sitting on its steps for about 20 minutes. He still has three bags when, at around 7:52 p.m., he gets up and starts walking. About a minute later, he is down to two bags. One is gone.

Around 8:30 p.m. that Saturday night, a blast would shake that street, strike passersby with shrapnel, send a dumpster and debris flying, and stun a community and a city that never has 9/11 too far from its mind.

Ahmad Khan Rahimi, 29, is accused of planting that bomb on W. 23rd St., another on W. 27th St., and bombs at two sites in New Jersey. At Federal District Court in Manhattan on Mon., Oct. 2, Rahimi’s trial began, with jurors hearing from people who were hurt that night, law enforcement that collected evidence and security footage, and, due to an outburst at the start of the trial, Rahimi himself.

‘THE HEAVENS HAD OPENED AND FALLEN DOWN’ | For Helena Ayeh, an architect who works from home at W. 23rd St., her plans for that Saturday night included shopping Downtown and then making dinner for herself.

“As I was walking home, suddenly I heard a very loud bang. There was a bang and a flash,” she recalled, calling it “deafening” and “blinding.” “I felt myself thrust upwards and forwards.”

She landed on her knees and was somehow in front of her apartment building. Ayeh, who wears glasses, still had the spectacles on, but “couldn’t see anything when I got up,” she told the court.

She searched for her keys, but said, “I felt the keys but I couldn’t see them.” Her arm was “full of blood,” and her “white shirt was covered in blood,” with Ayeh saying she “didn’t quite realize I was hurt.”

Ayeh turned, yelled for help, and couldn’t hear anything. “The heavens had opened and fallen down,” she said. She screamed.

Someone put their arm around her and led her to an ambulance. While in the ambulance she recalled asking a woman who was helping her if her eye was still there. The woman hesitated. Ayeh asked again, and, after what seemed like an eternity, the woman asking her, “Do you believe in God?”

Ayeh said she did, and recalled the woman replied, “Pray.”

After going to the hospital, a doctor told her she had a cut from the corner of her eye to the inside of her eye. After some time, her vision recovered to its prior state.

Vicki Fereia had been enjoying the evening with her husband and three kids, watching TV at her apartment at Selis Manor (135 W. 23rd St., btw. Sixth and Seventh Aves.). Selis Manor is a 14-story building for the blind, visually impaired and those with physical disabilities.

“We heard a boom sound,” she recalled, saying it was “like coming out of a movie.”

Her third-floor apartment was shaking, and she told her husband, “They’re trying to kill us!”

Fereia, who uses a walker and was helped into the witness box, said that the windows in her living room were broken, and shattered glass that was everywhere had to be cleaned up.

In a voice that started to waver, Fereia told the court she had to take counseling for seven months after the blast. “Thank God we’re alive and we prayed,” she said.

Arkeida Wilson and her friends were looking to catch a movie at the SVA Theatre at 333 W. 23rd St. (btw. Eighth and Ninth Aves.). They had eaten at a restaurant on the Lower East Side, and since it was a nice night, decided to walk to the theater.

“When the explosion went off, it was a very loud popping noise,” said Wilson, who lives in Brooklyn and is a clothing designer.

Separated from her friends, Wilson ran into one building, then another looking for “a safer place to hide,” she told the court.

Wilson said she was treated for multiple burn wounds and had debris in her body. Doctors removed most but not all the metal that was in her chest and legs. She told the court she has scars from that night, and has had trauma therapy for some time.

CRISIS AVERTED ON W. 27TH ST. | The prosecution called witnesses from businesses along W. 27th St., where another bomb was planted but did not go off. One witness described how security footage showed two men who noticed the bag and decided to go through it. They removed an object — a pressure cooker — from the bag, left it on the street, and then took the suitcase and left.

Chelsea resident Jane Schreibman noticed that pressure cooker. A friend had given her a call around 10 p.m. about the explosion on W. 23rd St. On her way to see what was happening, Schreibman told the court, “I saw something that caught my eye on the curb. It seemed strange.”

The pressure cooker had wires coming out of it and a white plastic bag attached to it, she said. Schreibman continued on her way but “it was lingering” in her mind. She said she thought it might have been a family getting rid of a child’s experiment.

“I was afraid it was a bomb,” she told the court, and proceeded to call 911 to report it when she got back to her apartment. The 911 call was played for the court. On Sept. 30, 2016, Schreibman received a Proclamation for reporting what she saw.

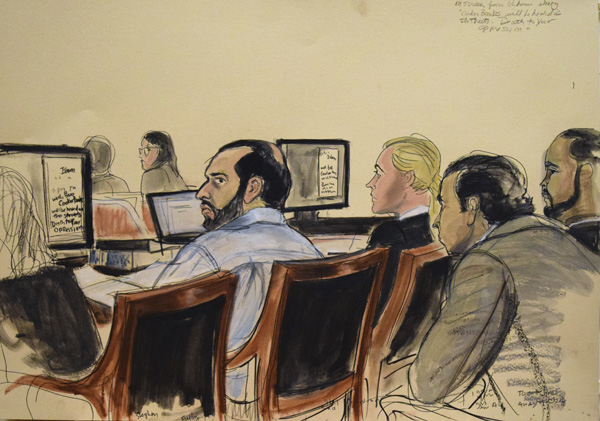

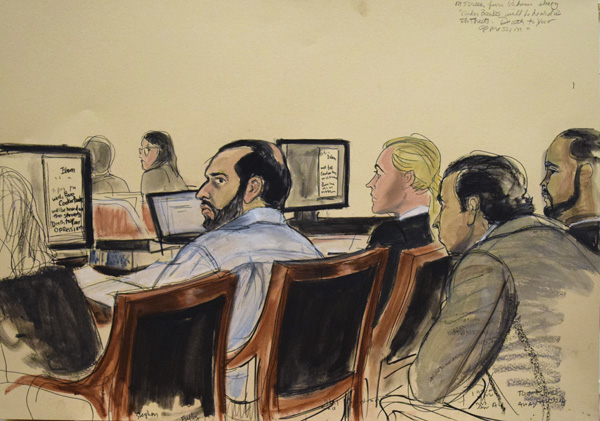

OUTBURST FROM THE DEFENDANT | At the start of the trial, Rahimi wanted to speak, and when US District Judge Richard Berman told him not at this time, he continued to talk. Rahimi was escorted out of the courtroom after standing up right when the prosecutor was going to give their opening statement, according to the New York Daily News.

“The whole year I’ve been waiting to get this thing across,” Rahimi said, according to the News.

Rahimi was brought back into the courtroom after the government made its opening statement. Wearing a light blue shirt, he said had no intention to cause a scene. His wife’s visa application is being held up, and he asked why he was being prevented from seeing her. He said he also had a visitation issue with his children — a younger brother was able to bring them to see him, but the brother was no longer on his list of permitted visitors.

“I’ve kept quiet for an entire year,” Rahimi told the court.

Berman said that neither Rahimi nor his defense attorneys had raised the visitation issue. The case, he said, had been going on for almost a year, and Rahimi’s attorneys had brought up “every imaginable issue on your behalf,” but not this.

“You’ve never raised it with me,” Berman said. He told Rahimi that if he was going to be in the courtroom, he cannot speak out of turn.

On Tues., Oct. 3, Berman noted the government had said it had two or three weeks of testimony from witnesses. This publication will continue to follow the trial.