Gov. Kathy Hochul legally has no authority under New York law to pause congestion pricing, a group of current and former New York lawmakers argued last week to a judge overseeing cases seeking to restart the waylaid Manhattan tolling program.

In an amicus brief filed in Manhattan Supreme Court on Aug. 21, three current and one former state lawmaker argued that New York law was explicitly designed to insulate public authorities like the MTA from interference by politicians when setting decisions like tolling rates.

When the four lawmakers — Brooklyn state Sen. Julia Salazar; Assembly Members Andrew Hevesi and Phil Steck of Queens and Albany, respectively; and former Manhattan Assembly Member Richard Gottfried — voted in favor of the Traffic Mobility Act of 2019, which established New York’s congestion pricing program, it explicitly delegated decisions on its implementation to the MTA, instead of the governor, they argue.

“By choosing the [MTA] Board instead of the Governor or the Commissioner of New York’s Department of Transportation, Amici delegated implementation of the TMA to a body that is insulated from political pressure or partisan politics,” the lawmakers wrote in the brief, which was first reported by Streetsblog. “By ignoring the legislature’s interest in making such an institutional choice, Governor Hochul subverts Amici’s interest in faithful execution of state laws.”

The brief is meant to support the argument of the plaintiffs — the City Club of New York, Christine Berthet, and Kathleen Treat — suing Hochul to restart the Manhattan toll.

In their suit filed last month, the plaintiffs say the original 2019 law granted authority to implement congestion pricing to the MTA, and policy decisions to the transit agency’s Board of Directors, not to the governor.

The legislators back that up by looking to distant and recent history. Lawmakers started creating public authorities in the first place to insulate their policies and financing from political machinations, and only give elected officials power over them when explicitly written into law, as was the case with the Port Authority more than a century ago, in 1921.

The Traffic Mobility Act has a “complete absence” of such explicit delegation, the lawmakers write, indicating “such a power does not exist.”

By 1953, the state created the New York City Transit Authority, the precursor to the MTA, with the intent of keeping it “free from interference by elected officials” following a fiscal crisis in the 1940s.

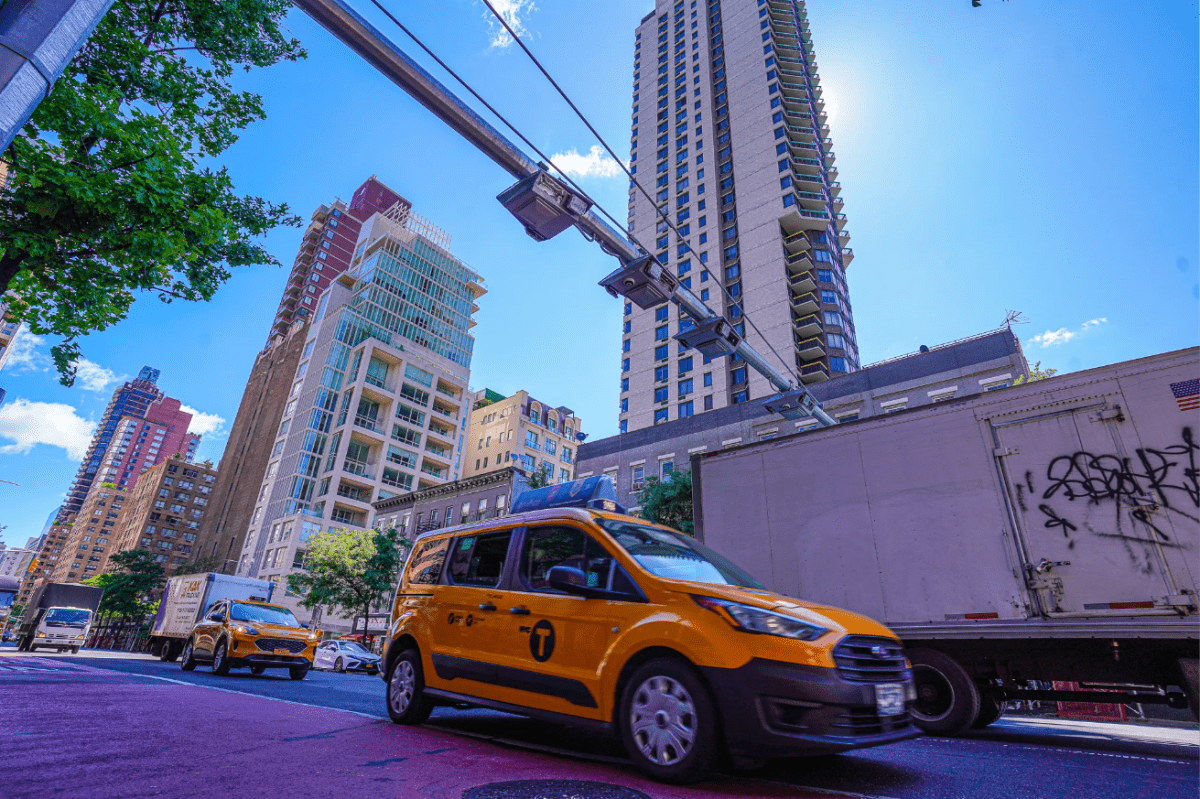

The impetus of congestion pricing was the 2017 “Summer of Hell” on the subways, when service reliability plummeted as a result of long-term disinvestment. Lawmakers and then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo ultimately landed on the Manhattan toll as a financing mechanism to modernize the system.

But the beleaguered Cuomo took pains to distance himself from the notion that he “controlled” the MTA and thus was responsible for its failures — something the lawmakers say supports the notion of an independent MTA.

“Giving governors an unwritten power to ‘indefinitely pause’ the MTA’s decisions creates confusion over who has ultimate political responsibility for imposing tolls on bridges and tunnels,” the lawmakers write. “Governors seeking to escape blame for such fees can defer to the MTA, citing its statutory authority; governors seeking credit for blocking fees could invoke some extra-statutory ‘pausing’ power.”

The governor appoints six of the MTA Board’s 17 members, as well as the chair; while the governor has substantial sway over the authority’s decisions as well as its purse, she technically does not control it.

Reached for comment, Hochul spokesperson John Lindsay said, “Like the majority of New Yorkers, Governor Hochul believes this is not the right time to implement congestion pricing. We can’t comment on litigation.”

Also filing an amicus brief were groups representing New Yorkers with disabilities, who struggle to use a system that is only 30% compliant under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Roughly $2 billion out of $5 billion the MTA planned to spend on disability access projects in the transit system under its 2020-24 capital plan — the largest investment in accessibility the authority has ever undertaken — are on ice due to Hochul’s pause on the toll. The groups say this puts an illegal and disproportionate harm on people with disabilities and urge the pause’s reversal.

Read more: Half of NYC Bus Riders Skip Fares as MTA Revenue Crisis Deepens