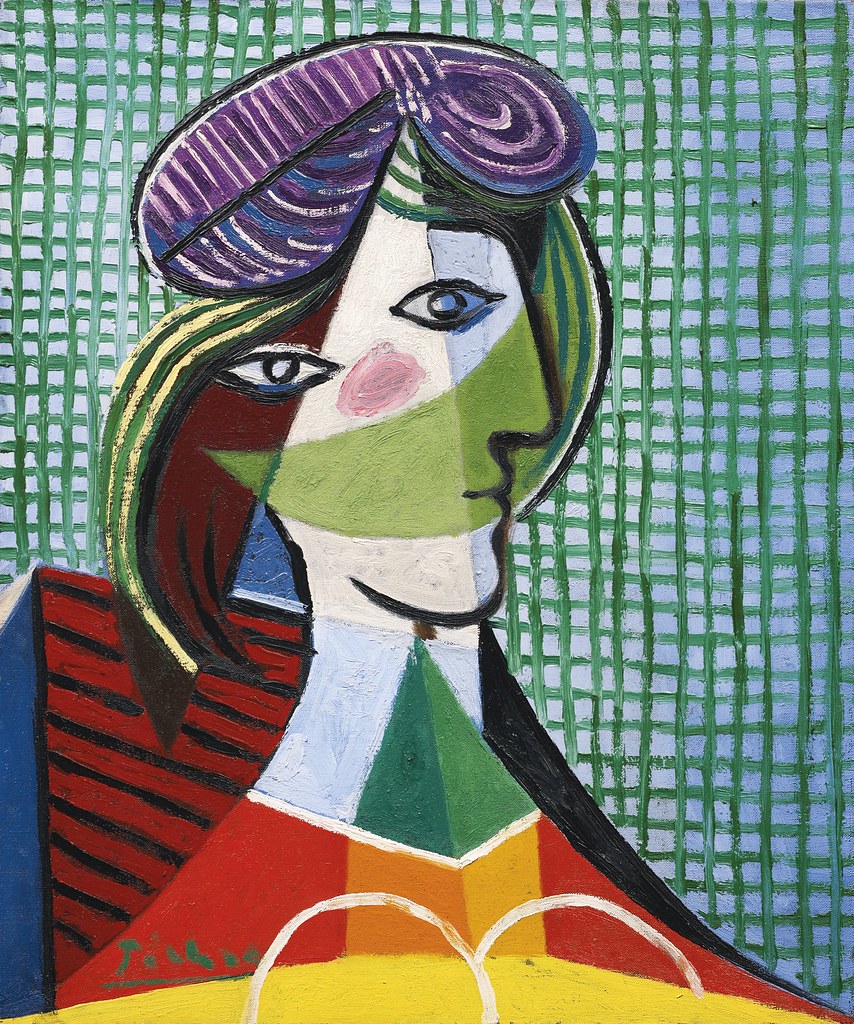

There she sits—Femme assise (Françoise)—etched in the tonal language of Pablo Picasso’s emotional geometry, a woman rendered not in joy or surrender, but in the frozen grace of observation.

Executed in 1945 and catalogued as Bloch 401 / Mourlot 45, this lithograph belongs to a quieter corner of Picasso’s postwar output. Yet it holds a profound charge: a testimony not only to artistic precision, but to the intimate power dynamics that drove the artist’s creative engine.

The subject is Françoise Gilot, a painter, intellectual, and the only one of Picasso’s lovers to leave him on her own terms. At the time of this portrait, Gilot was in her early twenties—curious, brilliant, and resistant to control. The year marked a turning point in Picasso’s life: it followed the dissolution of his volatile relationship with Dora Maar and coincided with Gilot’s first pregnancy. What is captured here is neither muse nor mistress, but a moment suspended between conquest and creation.

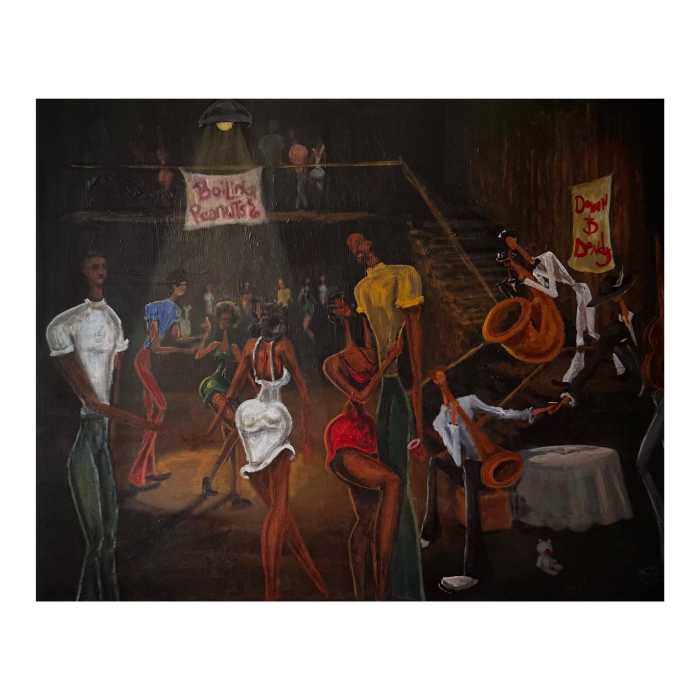

Historically, Femme assise (Françoise) holds significant value in Picasso’s lithographic evolution. During this period, he was immersing himself in the technical experimentation offered by the Mourlot studio in Paris. The lithograph allowed for immediacy, for the swift gestural clarity that characterized his postwar work. Within this particular piece, one finds Gilot depicted in spare, lyrical lines—her posture modest, her expression contained. It is a restrained vision of intimacy, yet it brims with possessiveness. She is present, but she is no longer her own.

The Muse as Medium, the Woman as Offering

To engage with Picasso’s work is to step into a complicated cathedral of genius—exquisite, unsettling, and unrepentantly male. He once remarked, “For me there are only two kinds of women—goddesses and doormats.” The remark, often repeated with smug detachment, provides a chilling key to the architecture of his creative life. His genius, as history has so often excused, required fuel. That fuel was frequently female.

From Fernande Olivier to Olga Khokhlova, from Marie-Thérèse Walter to Dora Maar, from Françoise Gilot to Jacqueline Roque, Picasso fed his mythos on the bodies, brilliance, and eventual unraveling of the women who loved him. They were not simply companions or collaborators; they were raw material. Their youth, their fertility, their madness, their silence—all of it became the pigment of his reputation.

One survived. Gilot left Picasso, raised their children alone, and wrote a memoir that defied him with clarity and dignity. The others did not fare as well. Maar was institutionalized. Walter died by suicide. Roque, his final wife, ended her life with a bullet. The portrait of artistic genius, so often hung in gold, has blood beneath the frame.

Value, Myth, and the Modern Market

Despite this legacy—or perhaps because of it—Picasso remains among the most powerful forces in the global art market. His name carries the weight of empire. Collectors, institutions, and private buyers continue to prize his work not only for its aesthetic legacy, but for its enduring cultural currency. To own a Picasso is to participate in the mythology of modernism itself.

Prints such as Femme assise (Françoise) represent a highly sought-after sector of this market. Works on paper from the 1940s and 1950s, especially those featuring Gilot, have grown increasingly desirable in recent years. Gilot’s cultural reappraisal—amplified by her own accomplishments and her eventual rejection of Picasso’s shadow—has elevated her portraits to a more complex tier of collector interest. These are not mere lithographs; they are historical artifacts of artistic and emotional consequence.

The print’s provenance and condition are essential to its value, but its power resides equally in its narrative. It is a record of a moment when the muse still sat for the master, before she rose and walked away.

Art as Consecration and Consequence

Femme assise (Françoise) demands more than admiration. It requires reckoning. Within its seemingly quiet frame lies a tension that refuses to resolve—a woman immortalized by a man who could not contain her, whose devotion to domination left wreckage beneath the brilliance.

To collect Picasso today is to carry this tension forward. His work is not merely beautiful. It is burdened, consecrated by sacrifice. The genius remains undeniable. The cost remains unanswered.

Françoise Gilot, seated in stillness, bears witness. She is not tragic. She is not erased. She is there, fully formed and sharply drawn—an image of what was, and of what refused to be lost.

Francoise is currently on view at DTR Modern Galleries Soho. Visit dtrmodern.com for more information.