Just over a week ago, the U.S. shocked the globe when it captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife Cilia Fores in a deadly raid, a move experts say has no legal basis.

But as American prosecutors pursue the ousted leader on drug and weapons trafficking charges, a pressing question remains: Will it ultimately matter if the administration’s Saturday morning capture of the Venezuelan leader was illegal?

“On the international plane, there’s simply no argument to be made for what the administration is doing,” said Brad Roth, an international law professor at Wayne State University. “There just isn’t even any articulated basis for this.”

The Trump administration says that invading Venezuela and kidnapping its leader was a law enforcement action, not a military one. But international law experts say that makes no sense.

“If law enforcement were the real rationale, then the logical conclusion from that would be the moment Maduro was apprehended, this would be over,” said Jeremy Paul, a professor at Northeastern University School of Law. “He was a criminal. We arrested him. He’s in custody. He’s going to go on trial.”

Trump, however, claimed in the wake of the arrest that the U.S. intends to “run” Venezuela.

“And now he’s talking about what we’re going to do with the oil fields,” Paul said. “I don’t see any rationale for using the military to create those deals.”

Maduro has been publicly named as a defendant since 2020 in the drug trafficking and machine gun possession case that’s been pending in the Southern District of New York for roughly 15 years. He, Flores and high-ranking Venezuelan officials were charged in a superseding indictment made public Saturday, which alleges they partnered with drug traffickers and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or the FARC, to “use cocaine as a weapon against America.”

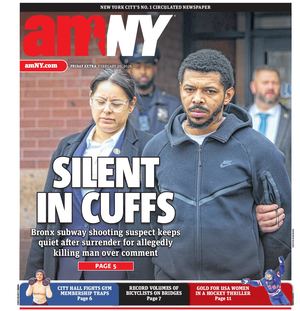

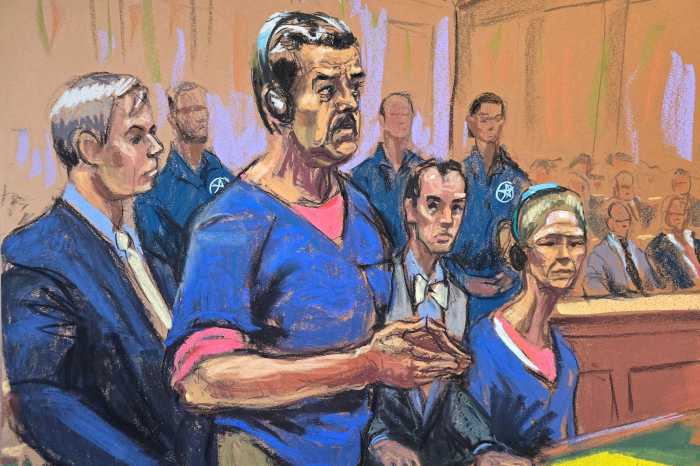

He and Flores pleaded not guilty to the charges at their Monday arraignment in Manhattan federal court, maintaining they were the rightful leader and first lady of their country, respectively.

“There is no justification for extraterritorial law enforcement,” Roth said. “To do a ‘snatch and grab’ of someone against whom you have an indictment in foreign territory is straightforwardly unlawful. The United States has done that sort of thing in the past, but no one has even really ever argued that it was lawful to do it, just that we could get away with doing it.”

Roth said Maduro’s capture was a “straightforward violation” of the United Nations Charter’s ban on member states threatening or using force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any other state.

“This was not law enforcement rules of engagement. They killed 80 people in doing this. They were relying on the idea that you can shoot first and ask questions afterwards, which are armed conflict rules of engagement, whether they admit it or not,” Roth added.

Experts also emphasized that the administration’s argument it was acting in self-defense because it was being “invaded by drugs” from Venezuela is not a strong counter to claims it violated international law.

As Maduro used his first court appearance in Manhattan to maintain he was still the president of his country and refer to himself as a prisoner of war, the United Nations met just three miles uptown, where a number of nations and the Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs Rosemary DiCarlo spoke against the United States’ actions.

“I remain deeply concerned that rules of international law have not been respected with regard to the Jan. 3 military action,” DiCarlo said. “The Charter enshrines the prohibition of the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”

Scores of prominent international law professors and attorneys have firmly held that not only have the Trump administration’s actions violated international law since the attack, they’ve also set a dangerous precedent.

However, Paul said the precedent Trump set is less dangerous if removing Maduro resulted in Venezuela becoming more democratic — like if he were to change his position on who should govern the country and began working with the opposition party headed by María Corina Machado and Edmundo González, whom the U.S. formally recognizes as the winner of the country’s 2024 election and head of state. Then, he said, the precedent set is that countries can use force against a sovereign nation in order to promote democracy.

But, as Roth emphasized, that’s not what’s currently happening. In recognizing Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodrieguez, who worked closely with Maduro and is publicly working with officials named in the same indictment Maduro and Flores are to run the country, as the country’s interim president, the Trump administration doesn’t have a claim to promoting democracy.

If Trump doesn’t stop working with Delcy and others who are charged in the indictment, Paul said, the U.S. sets a “terrible” precedent: that it would be “OK for any country to invade any other country at any time.”

“If no steps are taken to produce democracy in Venezuela, then the action will not only have been illegal but immoral,” Paul said.

Will it matter if Trump violated international law in Maduro’s case?

Almost certainly not, former federal prosecutors, defense attorneys and law professors told amNewYork Law. But Maduro’s defense team, led by attorney Barry Pollack of Washington, D.C.-based firm Harris St. Laurent & Wechsler, is all but certain to argue it should result in the case’s dismissal.

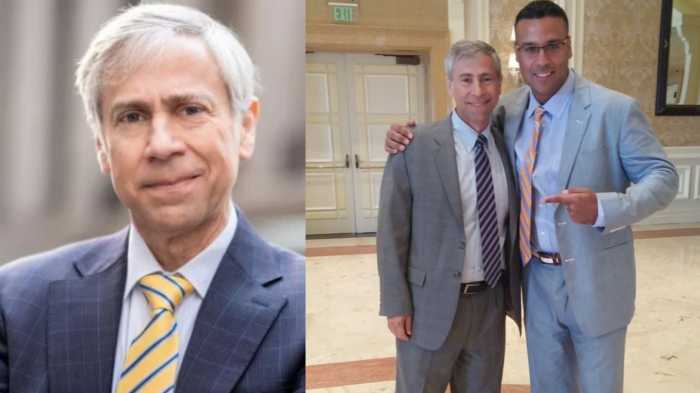

“I would assume that one of the first arguments you’re going to hear is that this was an abusive practice that the U.S. went through to get their hands on this man, and that’s not the appropriate way to drag somebody into their jurisdiction,” said Richard Gregorie, a former assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of Floridia who indicted a slew of high-profile international drug traffickers, including Manuel Noriega, Panama’s de facto leader in the 1980s.

“They’re subject to the charges, and the only thing that would upset that is if [the court] found that what the U.S. did was so abusive to the conscience of a reasonable human being that this shouldn’t go forward,” Gregorie said. “That’s a question that is going to come before the judge.”

However, U.S. courts have long held that it doesn’t matter how a person is brought into U.S. jurisdiction, even if it’s legally questionable. For example, Noriega, who was captured and brought to the United States from Panama in a manner similar to Maduro, made the same argument unsuccessfully.

“Our courts have routinely rejected that claim,” Paul said. “I don’t know why they’ve routinely rejected it, but they have, and therefore I don’t think that will work.”

The way domestic law has been applied over the past few decades makes it even less likely for the courts to take issue with what the administration did.

“It ought to be viewed that Trump has violated the constitutional scheme about how force is to be used abroad,” Roth said. “But the history of practice of the executive branch … really leads to the conclusion that there’s nothing currently that constrains the president from engaging in these kinds of acts.”

For example, Roth cited the U.S. kidnapping other heads of state to try them, like Noriega, and President Richard Nixon’s military actions in Cambodia without Congressional approval.

Additionally, the War Powers Resolution, which put additional checks on the president’s use of military force, has been held unconstitutional by every president who’s served since it passed in 1973 and isn’t credited with stopping any military action.

“The War Powers Resolution does not really tie the president’s hands,” Roth said. “The ‘declare war clause’ in Article I of the Constitution is not a prerequisite to the use of force abroad.”

Many experts hold that Trump didn’t commit an impeachable offense. And since international law comes second to domestic law in the U.S. and the United Nations Charter isn’t a self-executing treaty — the Supreme Court held in Medellín v. Texas that only self-executing treaties can be considered part of federal law in U.S. courts — it would be difficult for anyone to successfully argue Trump should face charges for any alleged international law violation.

What else is Maduro expected to argue?

Another of the first arguments Maduro’s defense team will use is that he should be immune to criminal charges, since he says he’s Venezuela’s head of state.

That claim is also likely to be unsuccessful, experts say, particularly because Maduro’s rule is considered illegitimate. Numerous reports show he remained in power despite losing the presidential election in 2024. The United States hasn’t recognized him as the head of state since 2018.

“In order to have head of state immunity [in the United States], you have to be recognized by the United States as the head of state,” Gregorie said.

Gregorie is intimately familiar with head of state immunity arguments; Noriega made the same ones, unsuccessfully. However, while Gregorie doubts Maduro’s will work, he does believe they’re different — and stronger — than Noriega’s were.

Most importantly, Noriega never officially held the title of president, whereas Maduro has been acting in an official capacity as Venezuela’s president. Additionally, the United States did recognize Maduro as the head of state from 2013-2019 — critically, for a portion of the time that the indictment charges the drug trafficking conspiracy had been taking place.

“That may make it make a whole different argument,” Gregorie said.

Gregorie also said he expects Maduro’s defense attorney to attempt to sever his case from his wife’s, and to sever the drug trafficking charges from the gun charges.

Experts also say Maduro’s defense team is likely to argue Venezuela takes drug trafficking seriously, has drug dealers, including government officials, in Venezuelan prisons and is involved in international drug interdiction.

“It was not the best, most robust program in Latin America, not like the well-funded Colombian one, but it existed and it was functioning, and [Maduro] commanded it and seemed to do it in good faith,” said Zachary Margulis-Ohnuma, a federal defense attorney who provided analysis on Maduro’s case to amNewYork Law based on publicly available information, on what he expects Maduro’s team to argue.

“I thought it was striking when, at the arraignment, Maduro said, ‘I’m not a bad person,’” Margulis-Ohnuma said. “What he’s talking about is the general repugnance that most people in the world, and in Latin America specifically, have towards drug traffickers. He thinks drug traffickers are bad people. I don’t think he’s ever going to admit to being a drug trafficker.”

Then there’s the question posed at every criminal trial: whether the government’s evidence is strong enough to convict.

Some attorneys have their doubts, including Margulis-Ohnuma, who represented Venezuelan General Hugo Carvajal, who was indicted alongside Maduro on drug trafficking charges in 2020 in the same case. Carvajal pleaded guilty and is awaiting sentencing.

He’s expected to testify against Maduro at trial, according to Gregorie, who worked on his indictment — but Margulis-Ohnuma says the government will need more than just witness cooperation.

“They haven’t publicly announced the existence of any of the usual things you see in a complex drug conspiracy, which would include not just cooperators, but also text messages, intercepted communications, wiretaps, taped conversations with cooperators that took place after they began cooperating,” Margulis-Ohnuma said. “There’s no hard evidence in the public record that he is a drug trafficker. There’s just accusations.”

When asked how it could be that there’d be enough evidence for Carvajal to plead guilty but not to convict Maduro in the same case, Margulis-Ohnuma said Carvajal’s guilty plea isn’t proof of Maduro’s guilt by any stretch of the imagination: The government still needs to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Maduro knowingly entered into the conspiracy he’s charged with, and the Supreme Court’s 2004 decision in Crawford v. Washington means that prosecutors can’t use an alleged co-conspirator’s guilty plea to prove another person is guilty of the same conspiracy, he said.

“Carvajal can be in a conspiracy, and that doesn’t necessarily make Maduro a member of the conspiracy,” Margulis-Ohnuma said.

Margulis-Ohnuma also said he has doubts about the persuasiveness, credibility and corroboration of those who may testify against Maduro, based on his opinion of witness testimony in related cases. Federal defense attorneys have emphasized that those testifying would primarily be those convicted on similar charges who are cooperating with the U.S. government, making them “desperate” and potentially incentivized to provide certain testimony.

Others disagreed that the government would have a difficult time coming up with the evidence on Maduro. Michael Nadler, a former federal prosecutor known for working on cases against high-profile Venezuelan officials, said the government wouldn’t have filed the indictment without the evidence to back it up.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that they have what they say they have,” Nadler said.

In terms of the witnesses the government will bring, Nadler said, “I imagine that they’re not going to have anybody that says, ‘Nicholas Maduro was flying planes out of Venezuela with kilos of cocaine.’”

“But what they will need is people saying, ‘Nicholas Maduro did more than turn a blind eye. He was somehow actively involved. He let it happen. He acknowledged it happened. He profited from it happening,’” Nadler continued. “This is, I imagine, all the different branches of the tree that they’re going to prove.”

Generally, getting witnesses to testify will be a difficult task, the former federal attorneys and professors agreed. Many who might have evidence on Maduro may be scared to testify out of fear of repercussions, a problem Gregorie has said he ran into in similar cases.

“Given the level of instability and uncertainty, I would imagine a lot of witnesses would be scared about testifying,” Paul said. “If you were Venezuelan, would you want to go to a public trial and testify against the former president? That’s pretty risky.”

Because a lot of the evidence against Maduro will be classified information, it’s likely the discovery process, or pre-trial period where the parties will determine what and how evidence can be used in the case, will take six months to a year, if not longer, Gregorie and Nadler said.

That’s because the government is likely to argue that significant portions of the evidence they want to bring against Maduro should remain under seal, something the defense would be set to argue against.

“The defense may claim, if they can’t get access to parts of the evidence, that it should be dismissed, or that the evidence should be prohibited,” Gregorie said.

While it’s possible Maduro will try to cut a deal with the government, or vice versa, it’s almost certain the case will go to trial.

“I don’t think Maduro is going to sign up to live the rest of his life in an American prison,” Margulis-Ohnuma said. “The way it doesn’t go to trial is that Trump makes one of his famous deals, where he lets Maduro go in return for something.”