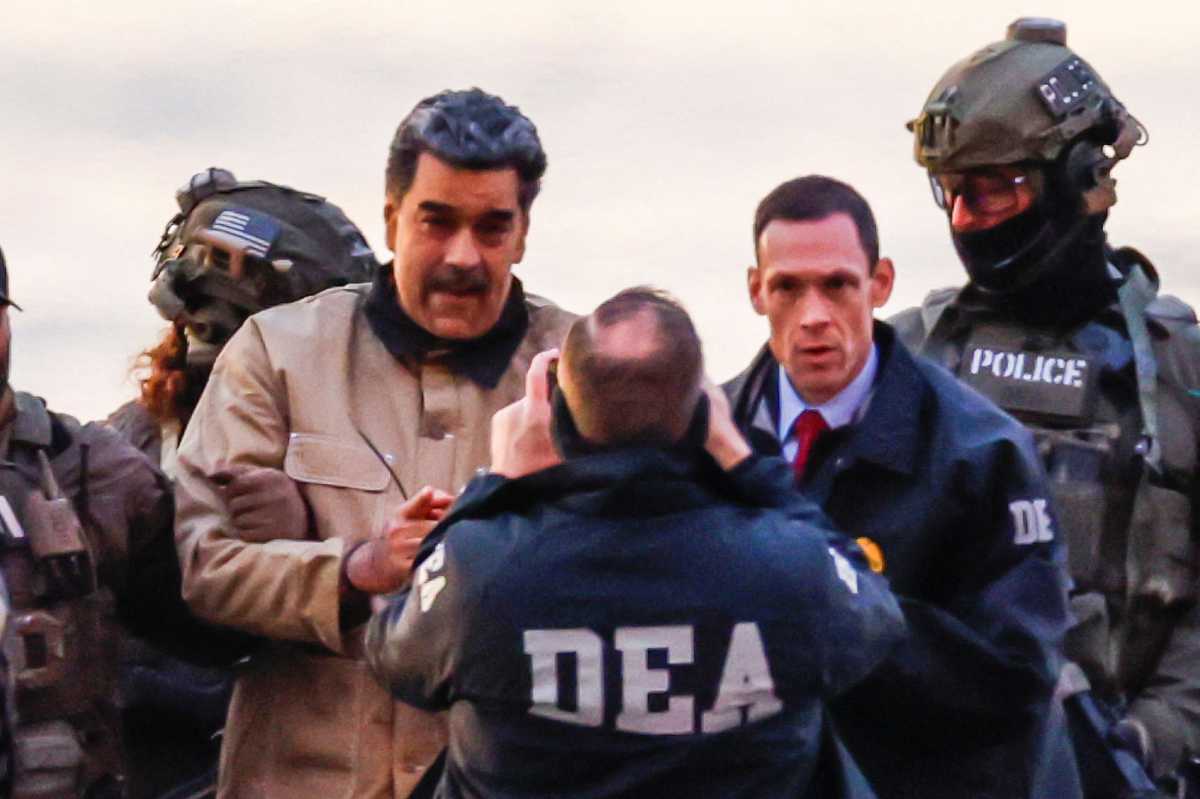

We may shed no tears for former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, charged with collaborating with drug cartels to traffic cocaine, but should he be denied protection from unreasonable searches and seizures conferred by the Fourth Amendment? This is the position that the government will undoubtedly (and with solid legal precedent) take. It may do so, strangely enough, simply because Maduro was abducted by U.S. law enforcement on his own soil.

Leaving all politics aside, his case poses a real juggling act for U.S. District Court Judge Alvin Hellerstein of the Southern District of New York. Earlier this year, in G.F.F. v. Trump, Hellerstein enjoined the U.S. government from summarily removing more than 200 aliens to El Salvador’s terrorism confinement center. His ruling rested on the plain wording of the Alien Enemies Act, which required meaningful notice, adequate time to marshal a legal defense, a hearing, and judicial review — all before physically removing foreigners from the U.S.

With Maduro, however, Hellerstein faces a seemingly impossible balancing act and that is whether he must afford full constitutional protections to those who cross the border unlawfully (as in G.F.F.), and simultaneously deny basic civil liberties to a foreign national forcibly brought before it by the United States, like Maduro?

Maduro argues that he was kidnapped by U.S. agents and while he certainly has the right to counsel and a fair trial, he will likely be deprived of Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches. In a tandem of cases (Ker v. Illinois and [1886] and Frisbee v. Collins [1952]) the United States Supreme Court held that the way a defendant is brought before the court (even if by force) as with Maduro, cannot divest a federal court of jurisdiction. This is the Ker-Frisbee doctrine; it has been the law of the land in three centuries and it is unlikely to fall now.

Our Supreme Court has taken it one step further. In addition to conferring the license to abduct, seemingly granted by Ker-Frisbee, in U.S. v. Verdugo-Urquidez (1990), the Court held that the Fourth Amendment does not protect a foreign national against the warrantless search of his home in Mexico by U.S. agents. Applying Verdugo-Urquidez to Maduro’s case, he would have no right against unreasonable searches at the time of his arrest by U.S. agents in Venezuela and evidence seized during his capture there including, potentially, electronic devices or financial records (material that could have been taken from his home without a warrant on U.S. soil) will come in despite apparent Fourth Amendment violations. Our court will probably offer no Fourth Amendment protection to him at all.

To be sure, Maduro is a despot who should face justice but the irony facing Hellerstien is unmistakable and the question of equal justice looms large now. In the deportation context, he found that foreigners physically present in the United States may not be deprived of liberty without full procedural safeguards. But will he find that Maduro, who was forcibly abducted from his own country, should be both subject to the jurisdiction of American courts and denied Fourth Amendment protections?

Douglas M. Nadjari, a former state prosecutor, is a partner at Ruskin Moscou Faltischek P.C. and a member of the firm’s health law, white collar crime and crisis management departments. He serves as co-chair of the Professional Discipline Committee of the New York State Bar Association’s Health Care Section and is an instructor at the Criminal Law Bootcamp at Tulane Law School.