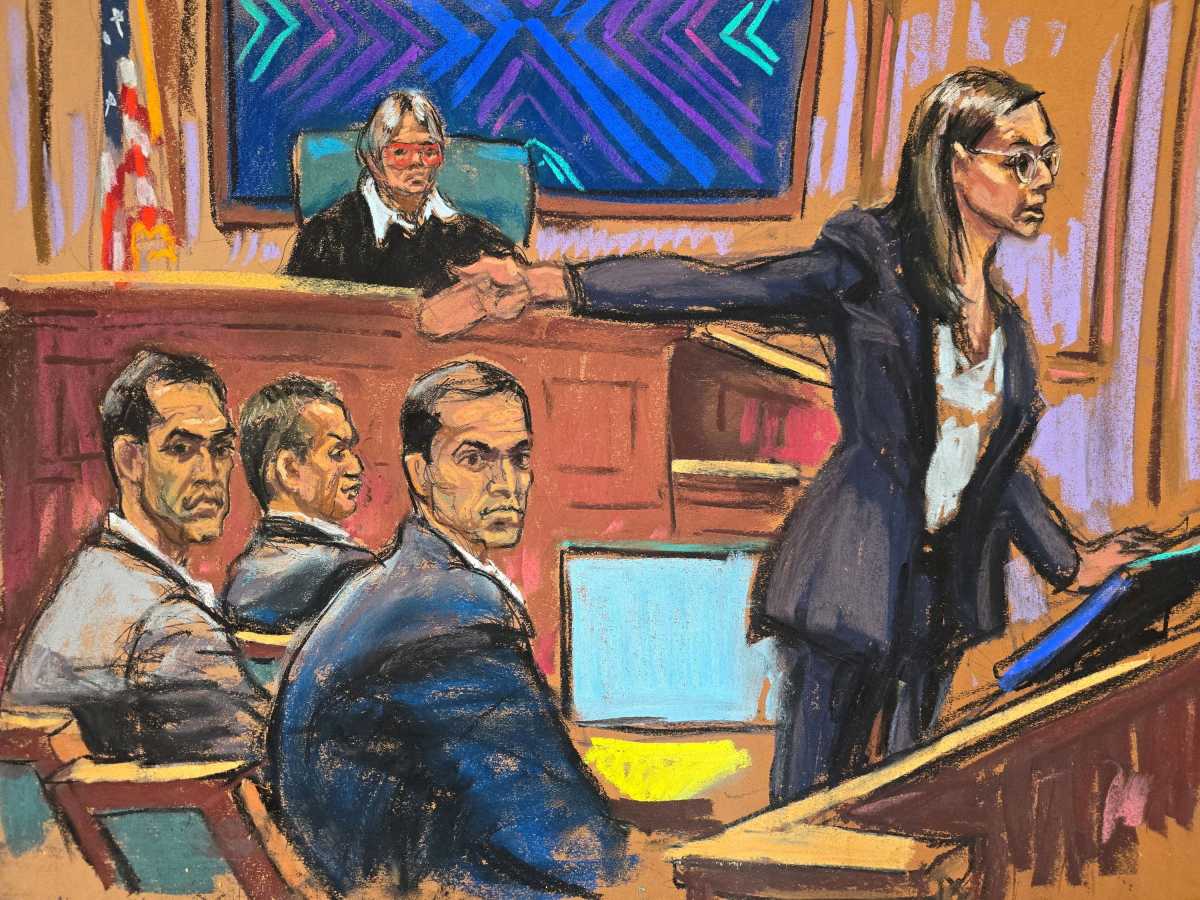

The sex trafficking trial of Oren, Tal, and Alon Alexander began on Tuesday with opening statements that were more functional than forceful — and fell short of the gravity this case demands. If any attorney made an impact, it was Deanna Paul, representing Tal Alexander, who presented the cleanest legal argument and a tone calibrated to the stakes. The rest? Competent, but uninspiring.

The courtroom itself signals the weight of the proceedings. U.S. District Judge Valerie Caproni of the Southern District of New York is running a tight ship — efficient, no-nonsense, and deeply aware of the media scrutiny surrounding the case. She’s given the lawyers virtually no leeway and has made clear that distractions, even technological ones, won’t be tolerated: jurors were explicitly instructed to disable push notifications on their phones to avoid any outside influence.

The jury, notably diverse: six men, six women, split evenly between white and Black or Hispanic jurors — appears attentive. This group will be asked to weigh deeply emotional and legally complex testimony from as many as 25 alleged victims.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Madison Smyser opened for the prosecution with a bold — if blunt — declaration:

“This case is about three brothers who worked together to rape girls. Woman after woman. Girl after girl. Rape after rape.”

She described a calculated pattern of abuse, alleging the brothers used promises of exclusive parties, vacations, and luxury access to lure women into situations where they were drugged and raped — sometimes simultaneously, sometimes recorded, and always celebrated in group chats and emails.

“They masqueraded as party boys when they were actual rapists,” Smyser told the jury.

But for all the intensity of her accusations, Smyser’s delivery lacked courtroom gravitas. She repeated the phrase “what the evidence will show” at least 10 times — a law school-safe approach, but hardly captivating. Dry and methodical, she delivered what felt like a federal practice exam opening — not a persuasive story for a jury. Worse, she lumped all three defendants together, missing an opportunity to differentiate culpability, and handed the defense a path to carve out reasonable doubt.

Federal sex trafficking, unlike rape or assault, requires a showing that something of value was exchanged for a sex act, and that this act occurred through force, fraud, or coercion. Smyser asserted she would prove that the women were offered value — access, drugs, travel, status — and that the sex that followed was coerced. She has some potent messages in her arsenal: Tal referring to victims as “cheap whores,” Oren texting that “no is not an option when it comes to sex.” But emotional shock alone won’t satisfy the elements of the crime.

Oren’s attorney, Teny Geragos, stood completely still in a black suit and opened with restraint:

“The government just told you a monstrous story. But the truth is something far more ordinary,” she said.

Geragos was smart, focused, and professional — but too dry to make a strong impression. Geragos framed her client as a “womanizer,” even a “playboy,” but firmly not a trafficker.

“This case did not start with a 911 call, a hospital report, or a drug screen. It started with civil suits looking for money,” the defense attorney said.

Her most effective moment came when she acknowledged the jury might disapprove of the lifestyle and vulgar messages: “Two things can be true at once — you can disapprove of their lifestyle and still find them not guilty.”

It was a crisp summary of the defense’s broader challenge: separate moral outrage from legal culpability.

Deanna Paul, representing Tal Alexander, gave the most thoughtful and controlled opening. She was well-paced, composed, and most importantly, she gave the jury a way to acquit without betraying their sense of morality.

She described the jury’s task as like “seeing an R-rated movie you never bought a ticket to.” Then she got to work, calmly reminding jurors that federal sex trafficking is not the same as rape, and that being shocked or saddened by testimony isn’t enough to convict.

She emphasized the narrow legal standards required: “You can believe rape or assault happened — without believing sex trafficking occurred. Those are state law charges, not federal charges.”

And Paul questioned the reliability of memory and the power of performance in the courtroom: “Memory does not get more reliable with time.”

Howard Srebnick, counsel for Alon Alexander, chose not to give an opening at all — a smart strategic choice. By deferring, he preserved flexibility and avoided being tarred by the same brush in the government’s broad-brush approach. With the prosecution grouping all three defendants together, the silence may work to his client’s benefit.

The trial is expected to last a month. The prosecution has promised a long line of witnesses — many testifying under pseudonyms — and deeply personal testimony. But the defense seems ready to argue that no amount of disturbing content can overcome what’s missing: evidence of trafficking, not just misconduct.

Opening statements are about shaping the lens through which jurors view the evidence. This week, the prosecution told a horrifying story. But the defense reminded them, perhaps more effectively, that stories aren’t convictions, and shock is not a substitute for proof.

Cary London is a civil rights attorney in New York City.