If all of New York City’s streets and sidewalks were laid out end to end, it would stretch three quarters of the way around the world. So why do they feel so crowded?

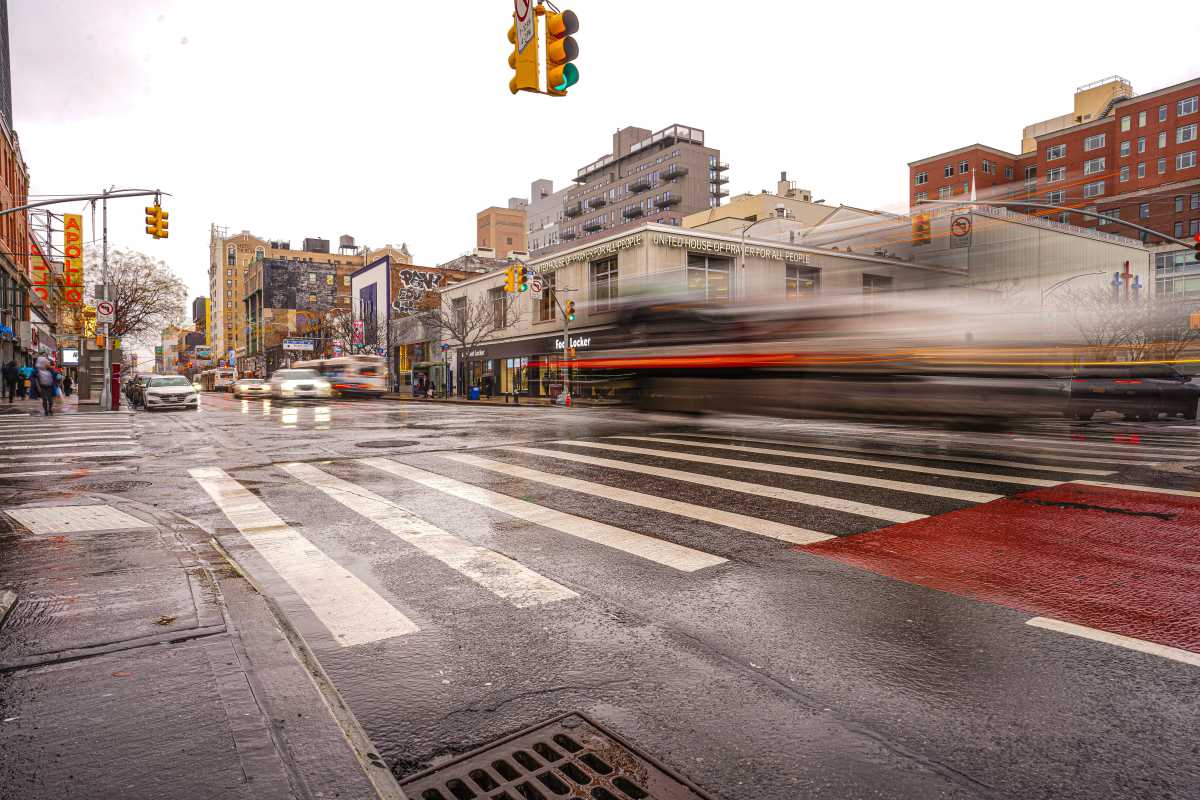

A large part of the answer is and always has been New York’s density, with Walt Whitman writing 165 years ago about the “tumultuous streets” and the “endless sliding, mincing, shuffling feet”. Today’s users are 8.25 eight million residents, about one million commuters a day and 62 million tourists a year.

But our relationship to the public realm, which includes plazas and parks and privately owned public spaces, has evolved because of social trends and new technology. As a result, the competition for its use has grown fiercer and more controversial.

The public realm has long been used for three key activities: transportation, recreation and commerce. But how these uses have manifested has changed and the distinctions between them have somewhat blurred.

Take transportation. While the need for separation of pedestrians and vehicles for safety reasons was self-evident, the Robert Moses era of highway building elevated the cars pedestrians. That started to change under the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his transportation commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan, who used her authority to create pedestrian plazas and bike lanes over the objections of drivers and businesses. Today, accommodation of those constituencies is taken for granted- except in some neighborhoods where expansion is proposed. But no one is calling for the removal of sitting areas in Times Square or eliminating the Brooklyn Greenway.

Even for cars, the modal use has changed with the introduction of ride-share apps, such as Uber and Lyft, which resulted in almost 100,000 ride share vehicles hitting the streets, compared to about 14,000 yellow taxis. On-demand shopping has made the Amazon van ubiquitous, as are e-bike food deliveries.

Many people make their living using the streets and sidewalks which reduces their availability for drivers and pedestrians. Think food vendors and film trucks, street fairs and scaffolding. All providing some value to the city and all insisting that they should be accommodated because they fill a public need. Reconciling these conflicting demands isn’t easy.

It’s a challenge to decide which uses should be favored. Take outdoor dining. Before the pandemic limited indoor activity, sidewalk cafes were viewed as impinging on the pedestrian experience in many places. The experiment of letting tables occupy street space during Covid was a success to excess, causing City Hall and the city council; to rein it in but making it a permanent seasonal addition to the streetscape.

It also led to a policy breakthrough, with restaurants charged per square foot of street used (higher in Midtown Manhattan, where cars are now charged just for using the streets). This has led to some discussion of whether the city should be compensated when streets are used as construction staging areas.

Recreation can be big business too. Corporate sponsored runs and bike races are boons to their participants and fans, less so to anyone who lives in the neighborhoods or near the parks through which they go. New Yorkers when the dark days of the 1970s were brightened by the first five-borough New York Marathon could scarcely imagine that it would attract two million spectators today. It helps make New York unique. Can the same be said about the 11 half marathons that will be run in Brooklyn alone between now and the end of the year?

Decision making about which uses should be permitted where and at what cost is diffuse. Pursuant to both state and local law, the use of public streets whether for vehicles, bikes or buses is primarily determined by NYC DOT. But street festival, block party, farmers market and health fair permits are issued by the Mayor’s Office of Citywide Event Coordination and Management, and street film permits come from the Mayor’s Office of Media & Entertainment.

Looking over their shoulders are elected officials, community boards and neighborhood associations, all of which may share an appreciation of a use in the abstract but less so when residents show up to say that their need for parking outweighs the interests of a transient biker or tourist.

Recognizing that the competition for public space had reached a tipping point, in February, 2023, Mayor Eric Adams created the position of “Chief Public Realm Officer” tasked with leading inter-agency collaboration and driving innovation. While the position was not granted decision authority, his first appointee, Ya-Ting Liu continues to hold the position of chief strategy officer for the deputy mayor for operations to which most of the relevant commissioners report.

“In New York City, the public realm is everyone’s living room. It’s where we eat, play, and gather,” Liu said, “Having beautiful public spaces accessible to all people is one of our greatest assets — it is what makes New York City so special.” But the public realm is one area where, as Mayor Adams would say, we are a city of eight million people with eight billion opinions.

Former NYC Council Member Ken Fisher is a member of the national law firm of Cozen O’Connor whose practice concentrates on NYS and NYC regulations, transactions and investigations. The opinions expressed are his own.