By Ed Gold

Bernard “Jack” Heineman, Jr., a longtime Villager with many interests, who parlayed love of art, strong family ties, community activism, extensive travel, anecdotal skills and a mischievous sense of humor into what he called “an absolutely wonderful life,” died on Nov, 5 at his longtime home on Bank St. at the age of 82.

His death was sudden and presumably from a heart attack, according to members of his family.

His mother, a member of the Morgenthau family, was responsible for calling him Jack; she named him in honor of her young brother who had died.

His community activity included a trusteeship at St. Vincent’s hospital, and early membership in the fledgling Village Democratic reform movement in the late 1950s and early ’60s.

He served with distinction in World War II in the Sixth Armored Division, part of Patton’s Third Army, and was awarded two bronze stars and two silver stars.

His activities were eclectic, to say the least. While he was a partner in a textile brokerage in his early career, he actually retired from corporate activity in his 40s, according to his daughter, Deborah, to concentrate on his varied interests.

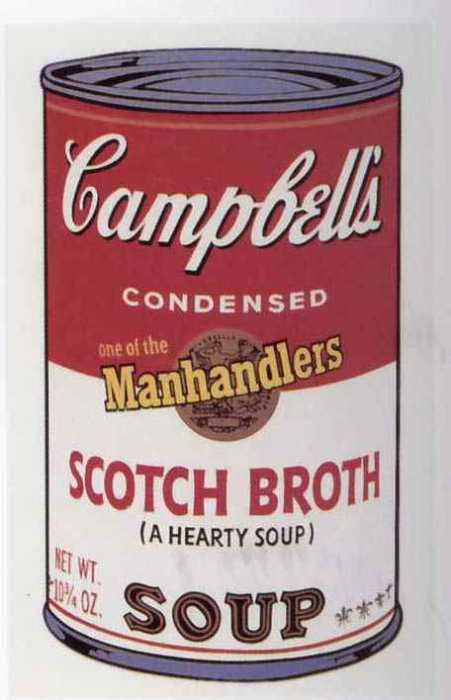

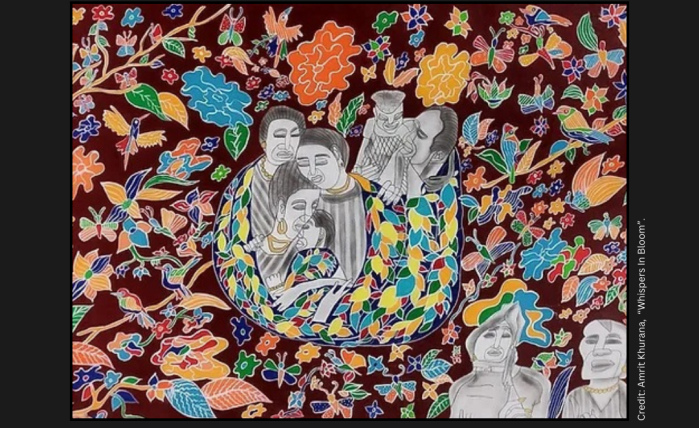

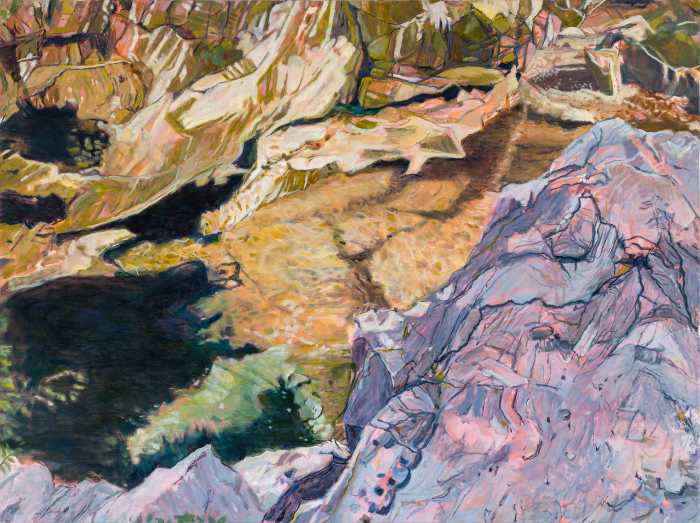

Possibly his most conspicuous activity was as a lover of art. When he was still in college at Williams he developed an affection for the Ashcan School of artists, who depicted daily urban life in its various nuances, essentially unromantic. He began collecting watercolors that many others in the art field considered unattractive and depressing.

Always an independent thinker, he continued to tout the art he loved, including works by some of the top Ashcan painters, such as Maurice Prendergast, among others, according to his daughter. It turned out he had favored a winning artistic school and would over the years loan works to museums as well as his alma mater, Williams College.

Several Heineman generations have attended that liberal arts college in Massachusetts, including daughter Deborah and son Matthew. His third child, Steven, attended St. Lawrence College but appeared in a film at Williams so his dad could claim all of his children had gone to his beloved school. Some of his grandchildren are bound for Williams as well, and they will no doubt feel at home in a meeting place called the Heineman Living Room.

Thanks to Heineman’s father, Bernard Sr., known as Barney, Heineman Jr. did a lot of traveling to help build his father’s collection as a lepidopterist — a person who studies butterflies and moths. The family collected more than 7,000 specimens, which have since been donated to a museum.

In fact, it was on a butterfly hunt in India that Heineman met his wife-to-be, Ruth Kress. They were married in 1955; she died in l998 after a lengthy battle with cancer.

Several longtime Villagers have fond memories of Jack Heineman. Miriam Bockman, a former Manhattan Democratic County leader in Manhattan and district leader out of Village Independent Democrats, recalled their friendship:

“We both belonged to Care Givers to learn how to cope with spouses who were seriously ill,” said Bockman, whose husband had Parkinson’s. “What I remembered about Jack was his sensitivity to other people’s problems.”

With a touch of humor, she added, “I recall he favored very loud ties.”

Another friend of more than half a century, Jo LoCicero, who had been an important educator in the city, knew both of the Heinemans well through their children. She and Ruth had met with their very young offspring in Washington Square Park, and as the children reached school age they both became active in the P.T.A. at P.S. 41.

LoCicero recalled: “I always looked forward to seeing Jack because he loved to laugh and both of my daughters adored him.”

While Heineman was very traditional in some areas, like calling friends on their birthdays, he could also be very playful. On one occasion he ran into a Village friend talking to a female neighbor. He walked over and sternly asked: “Does your wife know you’re carrying on this way?” Recovering from an operation, he told visitors why he had picked out his room in the Coleman Building at St. Vincent’s hospital: “I can see my house from here,” he explained, “and can check up on my wife’s activities.”

He was big on culture and family gatherings. There was lots of theater and ballet, and a family get-together in the summer at the Thousand Islands in Clayton in Upstate New York.

The Heinemans actually own the largest of the islands, Picton Island, which Heineman Sr. had bought during the Depression in the ’30s for a song and which now would sell for seven figures.

Heineman’s religious associations were eclectic. An earlier family member had been the first rabbi in Boston. His daughter said her father had a strong spiritual side, but didn’t belong to any denomination and was comfortable at services in churches as well as synagogues. He could be called a humanist, she added.

Funeral services were held Nov. 10 at St. John’s Episcopal Church in the Village, which was near the Heineman home and one frequently attended by his wife.

During the funeral service, the homily was delivered by Reverend Lloyd Prator who suggested, “God knows Jack very well. They are on a first-name basis.” His son Matthew summed up his father with the words: “He celebrated life.”

There was testimony on the strong ethical strain in the Heineman family at a reception following the service.

Mark Schmidek told of how Jack’s father, with support from his wife and children, had served as sponsor of the Schmidek family in helping them escape from Nazi Germany in the ’30s.

Schmidek explained that his mother’s maiden name was Heineman, so his family had written Bernard Sr. in the hopes that they were relatives. It turned out they were not related. But the American Heineman family agreed to sign an affidavit indicating they were related, and the Schmideks were able to escape the Holocaust, their last family member leaving Germany just before the infamous Kristallnacht, when the Jews were terrorized.

“I would not be alive,” Schmidek said, “were it not for the Heineman family.”

In addition to his three children and their spouses, Heineman is survived by two brothers, William and Andrew, and six grandchildren.

The family suggests that those wishing to honor his memory send contributions to St. Vincent’s hospital or Williams College.