The memorial under the Washington Square Arch, listing the names of the nightspots where the victims were killed, such as Casa Nostra, a popular pizzeria, and Le Bataclan concert hall.

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Updated Wed., Nov. 18: Hundreds of shell-shocked French expatriates and French Americans rallied in Washington Square Park Saturday afternoon to mourn and come together after Friday evening’s ISIS-related terrorist attacks in Paris that left more than 130 dead and 350 injured.

Shortly after 2 p.m., Mayor Bill de Blasio joined them, making his way through the crowd to leave a bunch of white roses at a memorial under the arch.

The tall mayor’s head towered above the sea of people gathered in the park, as the sun streamed through the arch. Amid the crowd, Tricolor flags fluttered on the brisk and windy day.

“Vive la France!” de Blasio said, as the crowd cheered softly. He then joined them as they launched into the “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem, again, rather softly.

Mayor Bill de Blasio arriving at Saturday’s vigil with a bouquet of white roses and lilies, which he left on a memorial under the arch.

“Contre nous de la tyrannie / L’étendard sanglant est levé…Marchons, marchons!…” (Against us tyranny’s bloody banner is raised…march, march!…)

“We can’t change our values,” the mayor told them, adding, “You will persevere.”

On signs held aloft and painted on some people’s cheeks was the Eiffel Tower in a circle — in the shape of a peace sign — a symbol of hope in the wake of the bloody rampage.

During a press conference, de Blasio — with Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito by his side — urged France not to waiver from its ideals.

The Tricolor, the French flag, proudly flew by the arch.

“Stay strong and send a message to the terrorists that they cannot win,” he urged.

Since 9/11, the mayor said, the New York Police Department has diligently combated terrorism here, and will continue to do so.

“Fourteen years in this city, we have been able to stop numerous terrorist attacks,” he said.

John Miller, the deputy commissioner of intelligence and counter-terrorism, said the N.Y.P.D. has a unit of 400 officers whose sole full-time duty is counter-terrorism.

“We know that in this country we’re the number one terrorist target,” de Blasio said.

The mayor added that 9/11 disrupted a primary election day — including a mayoral primary — but that the election was held soon afterward, just two weeks later.

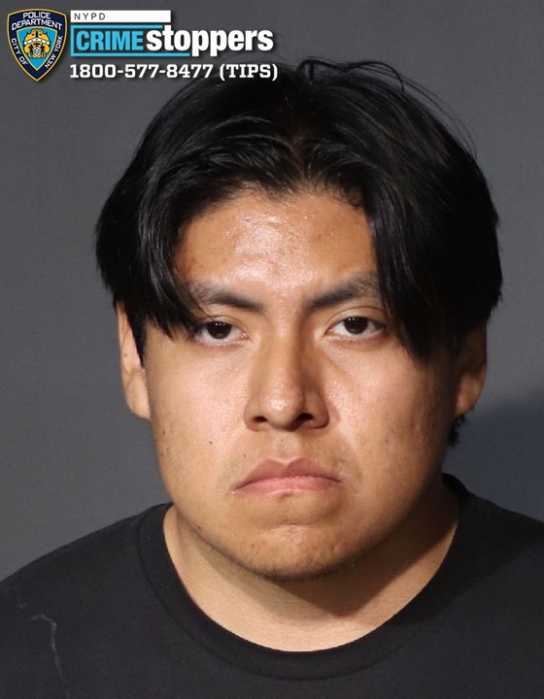

Anais Bambili, left, who had just learned her best friend’s boyfriend died in the Paris attacks, was consoled by her friend Sophie Gousset at Saturday’s vigil in Washington Square.

“We wanted to show that we could recover, and recover quickly,” he said. “My advice to Paris is to be resolute and to return it to the great city it is.”

Trailed by news photographers, the mayor then visited police posted in the nearby N/R subway station, a photo-op to illustrate the city’s readiness.

Later in the evening, de Blasio returned to Washington Square to light the arch in the colors of the French flag. Earlier a small Tricolor flag had been hung from the top of the arch.

In a statement, police said, “There is no known indication that the attack has any nexus to New York City.” But police said they would adjust their deployments and post heavily armed Hercules units at key locations as a visible deterrent.

Those gathered in the park for the vigil were mainly the young — for this time it was they who were targeted in the worst outbreak of violence in France since World War II.

Sadly, it was the second time this year that the French had gathered in Washington Square to mourn. In early January, Muslim gunmen killed 11 people at the Paris office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. One of the terrorists reportedly had yelled that they had “avenged the Prophet Mohammed.” Two days later, in a related incident, a gunman killed four Jewish hostages at a Paris kosher supermarket.

Friends Laura-Jane Gautier, 26 and Delphine Turoy, 25, were in New York visiting from Paris.

“It’s terrible,” said Gautier, a journalist. “There are no words — so much hate and so much pain.”

Turoy, an artist, said, “Closed borders. The media is saying, ‘It’s the war.’ But we don’t know what is the war.”

“It’s our heart being murdered,” read a woman’s sign at the vigil.

Turoy lives on Rue de Charonne, where the gunmen strafed the sidewalk cafe of La Belle Équipe cafe, killing 19 and wounding nine.

A friend of Gautier’s was in Le Bataclan, the famed music venue, where several heavily armed men burst in during a show by the American band Eagles of Death Metal and slew at least 89 people.

“I have a friend who was in the concert hall,” Gautier said. “But he managed to escape somehow. He was covered with blood. To escape, he walked on people.”

That friend was receiving psychological counselling in a “crisis room” set up to help the traumatized victims recover, she said.

In a feeling akin to what New Yorkers experienced in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 — namely, the fear of more terrorist attacks — Gautier admitted she was feeling jittery about returning. But they planned to go back.

“Strangely, I want to be there,” she said.

Carla Beye, 28, recently arrived in New York for a two-year stint with Lacoste as a Web project manager. Her apartment in Paris is on Rue Richard-Lenoir, right near Le Bataclan.

“So, I imagine it was me, my family, my friends,” she said of the attack’s victims.

She said she read on Facebook that a cousin’s friend was fatally shot by one of the terrorists as she sat in her car.

“And I don’t want to come back to France right now,” Beye said.

She added she would like to see a voter referendum on whether France should be bombing the Islamic State. Asked if she thought France ought to get out of Syria, she said, “Maybe, yes.”

However, as of Monday, it was reported that her homeland had already massively retaliated with increased bombing strikes against the militant group.

Nearby, next to the arch’s eastern leg, a woman was wracked with sobs as she held a cell phone to her ear.

Managing to compose herself, Anais Bambili, 24, said, “A boyfriend of my best friend was eating on Rue de Charonne. He was wounded. He went to the hospital. I just got a call — he just died.”

Bambili, who is studying English and living in Brooklyn, was being consoled by her friend Sophie Gousset. Also in her twenties, Gousset said two of her friends were shot during the night of terror.

“It’s like the only place we hang out — and Place Voltaire,” Bambili explained of the area where the terrorists wreaked their carnage. “There are a lot of cafes — it’s not very expensive — and bars, concerts.”

Marion Merigot, a theater producer living in New York with her family, said the 11th arrondissement, on the Right Bank, which was ground zero for the coordinated attacks, is like the East Village.

“It’s families, young people, bobos [bourgeois bohemians], hipsters, everybody,” she said.

Asked if she knew anyone who was injured, she said, “Not personally, but a friend of a friend was killed.”

“I hope they respond firmly,” she added.

Her precocious daughter, Sasha, 12, who attends the Lycée Français, was similarly resolute.

“I think it’s the biggest one yet,” she reflected seriously of the attack. “And it’s not that far after the Charlie Hebdo attack, and it’s meant to scare us. But we’re not afraid.”

Meanwhile, Merigot’s smiling son, Noe, 8, sat nearby on her husband Nicholas’s shoulders holding up a red-white-and-blue “Paris” sign.

French patriotism was on display, and on cheeks, too, at the vigil.

Two Lycée Français grads, French Americans Hannah Overlaw and Pauline Balsamo, both 27, said the attack had brought “a sense of solidarity” to New York’s French community.

When 9/11 happened, they were “pretty young,” Balsamo admitted. This time, though, this is affecting her more deeply.

As for the vigil’s crowd estimate, she said 1,000 people had posted on Facebook that they would be attending.

While the terrorists hoped to strike fear into the hearts of young people, especially, it won’t work, they predicted.

“You have to go out,” Balsamo stated matter of factly.

Standing holding a French flag on the south side of the Washington Square fountain, Matilde Brault, 23, and Pierre, 21, who only gave his first name, both agreed that the attack was over the coalition’s bombing of the Islamic State. The attackers had said so, survivors reported. Asked if they felt there would now be a backlash against French Muslims, Pierre, who is studying at Columbia, didn’t think so.

“Charlie Hebdo was perceived as a Muslim issue,” he said. “This was seen as an ISIL issue — and I feel good about that.”

Yet, some peace activists worried that there would, in fact, be a negative backlash — against civil liberties, in general. Reverend Billy, the local performance-artist anti-consumerist preacher, for one, expressed his concern in a Facebook post shortly after the attacks.

“I have a riot of confusion in my soul,” he wrote. “Ours is a cultural attack on a culture of consumption; has always been an effort to expose France-style colonialism, how it manifests in the sweatshops of big retail, and…the military defense of profiteers. How American! And now when it is met with this cruelty, all the nationalist fears are unleashed… This is a time of horror and sorrow for some, for whom we pray. There is also a foreboding feeling for all of us… . ”

The Washington Square Arch was lit in the colors of the French flag on Saturday evening.