The Lower Manhattan Historical Society fought hard to convince the City Council to co-name Bowling Green as Evacuation Day Plaza to commemorate when the British finally surrendered Lower Manhattan to George Washington on Nov. 25, 1783.

Members of the the Veteran Corps of Artillery of the State of New York raise the 13-star colonial flag over Evacuation Day Plaza.

BY BILL EGBERT

Well-fed patriots and history buffs turned out at Bowling Green the day after Thanksgiving to celebrate Evacuation Day, commemorating when the British finally surrendered Lower Manhattan to George Washington on Nov. 25, 1783, effectively marking the end of the Revolutionary War.

For nearly a century after Washington’s triumphant return to Downtown Manhattan, Americans nationwide celebrated Evacuation Day nearly as fervently as the Fourth of July. But interest faded during the late 19th century — especially after the Civil War, when Thanksgiving took over the last week of November. New Yorkers still held annual parades into the early 20th century, but formal celebrations ended entirely in 1916 when the United States entered World War I as an ally of Great Britain.

But a group of Downtown history buffs revived commemorations of America’s “forgotten holiday” in Lower Manhattan a few years ago, and last year succeeded in having Bowling Green officially co-named Evacuation Day Plaza in its honor. On Nov. 25 this year, they gathered at the nation’s first public park to reenact the events that unfolded there 233 years ago, for the first time under the newly installed street sign immortalizing the historic moment.

“The purpose of this ceremony is to help New Yorkers understand the great historical significance of this area of Lower Manhattan,” said James Kaplan, president and co-founder of the Lower Manhattan Historical Society. “By reviving the very important but long-forgotten holiday of Evacuation Day we hope to educate New Yorkers and others about the importance of New York City’s Revolutionary War history, and create a new historical tourist attraction in New York City.”

On Nov. 25, 1783, as the last British forces departed Lower Manhattan — which they had occupied for seven years since George Washington’s retreat from the city following the Battle of Brooklyn, and for three years after hostilities ended — Washington finally returned to Downtown, and sent orders ahead that the Stars and Stripes should be flying above Bowling Green upon his arrival.

But those cheeky Brits had nailed the Union Jack to the top of the flag pole — and then greased the pole — before they departed.

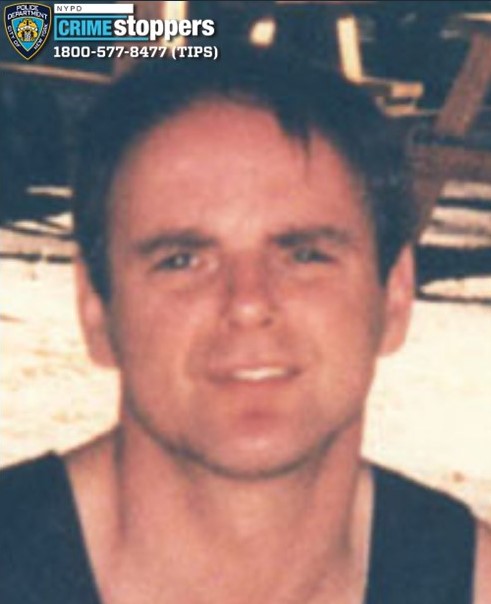

John Van Arsdale replaces the Union Jack with the Stars and Stripes on Evacuation Day, Nov. 25, 1783.

Several patriots tried and failed to reach the top of the pole and tear down the hated Union Jack, but one war veteran named John Van Arsdale managed to shimmy up the pole to deal with this final insult.

Van Arsdale had nearly died on one of the notorious British prison ships anchored in New York Harbor. For the duration of the Revolutionary War, with Lower Manhattan as its continental headquarters, Britain maintained a floating gulag where American patriots were treated not as prisoners of war but as rebels against the English Crown, entitled to nothing — not even food — killing more Americans than all the battles of the Revolutionary War combined, accounting for two thirds of colonial casualties.

As one of the fortunate 20 percent who survived the prison ships, it shouldn’t be surprising that Van Arsdale was also lucky enough to reach the top and rip down the Union Jack — and replace it with the American flag before the British fleet managed to sail out of sight.

In Friday’s commemoration of those events, members of the Veteran Corps of Artillery of the State of New York — the nation’s oldest continuously active military unit, which was formed in 1790 by Van Arsdale himself — marched from Federal Hall, America’s first seat of government, to Bowling Green, the nation’s first public park, and ceremonially lowered the Union Jack and raised the 13-star colonial flag.