BY YANNIC RACK | A public meeting addressing options put forth by the MTA in response to subway tunnel damage from Hurricane Sandy became a platform to float the notion of turning 14th St. into a bike-and-bus-exclusive thoroughfare — during, and possibly after, the repair process that could shut down L train service in Manhattan for more than a year.

State Senator Brad Hoylman, building on a previous report from a public policy think tank, asked the MTA to consider making 14th St. a dedicated bus and bike route to facilitate commuter alternatives during the May 12 meeting organized by the agency.

“I’d really like to see the possibility that you consider closing 14th Street to traffic,” the senator said during the event, held at the Salvation Army Centennial Memorial Temple Theatre (120 W. 14th St., btw. Sixth & Seventh Aves.), earning cheers and applause from the audience.

“And maybe, after this is done, we’ll consider keeping 14th Street closed to traffic,” he added.

Hoylman’s comments came on the heels of an April report from the Regional Plan Association, which originally floated the 14th St. idea as one strategy to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of daily L train riders who will be looking for replacement service if the line is shut down.

The report suggests restricting 14th St. between Union Square and Sixth Ave. in both directions to buses, bikes and pedestrians, with trucks permitted to make overnight deliveries or use loading zones on nearby avenues that would take the place of parking spaces.

Under the proposal, the rest of traffic could travel east of Union Square and west of Sixth Ave., but only one-way toward each river.

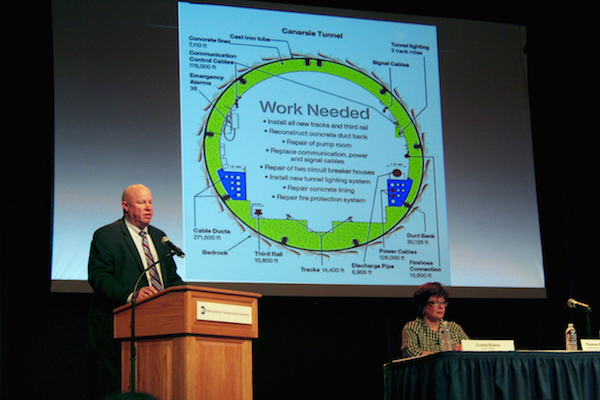

The planning exercise was sparked by the MTA’s plans to shut down the Canarsie Tunnel, which carries L trains below the East River, starting in 2019 to repair extensive damage that was caused by Hurricane Sandy when the superstorm flooded the 92-year-old tunnel with seven million gallons of corrosive saltwater.

The agency is currently mulling over two scenarios for the repair work: the first would close both tunnel tubes for 18 months, shutting down L train service completely in Manhattan, while the second would only close a single track for three years, which would still allow for trains to shuttle across the borough, but less frequently.

Reduced Manhattan service is not possible under the first proposal — the “get in, get done, get out” option, according to MTA Chairman and CEO Thomas Prendergast — since the agency says it won’t be able to keep trains running on the island without connection to a maintenance yard in Brooklyn.

“There isn’t a yard in Manhattan, and we can’t otherwise service the trains that would be stuck in Manhattan,” explained Veronique Hakim, the MTA’s President of New York City Transit.

Under the second option, trains would still be running both ways, but only carry about one fifth of the commuters that currently use the line, according to the MTA.

The agency says that 225,000 daily riders would be affected by the shutdown, with around 50,000 travelling solely in Manhattan.

“[There’s] an awful lot of ridership and volume along the 14th Street corridor,” said Prendergast.

MTA officials at the meeting did not respond directly to Hoylman’s comments, but Hakim later gave a vague answer to a similar question from Christine Berthet, the former chair of Community Board 4, who asked whether cars would be restricted on the street.

“On dedicated bus lines, and restricting cars and other types of vehicles on 14th Street — working with city DOT [Department of Transportation], on making 14th Street work is obviously a top priority here,” she said.

This week, DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg said the department would consider closing the street.

“Everything is going to be on the table,” Trottenberg said when asked by Councilmember Corey Johnson if banishing cars from the stretch was a possibility during a City Council hearing on Tuesday.

“We’re going to look at every option pretty seriously. We know this is going to be a huge challenge for the local population,” she said.

Either way, the MTA is already planning to help alleviate the strain of reduced L train service with a range of improved alternative transport options.

Under both scenarios, additional M, J and G trains would run to accommodate commuters, with J and Z trains making local stops between Myrtle and Marcy Aves. in Brooklyn. Free out-of-system transfers would be provided between the Broadway G and Lorimer St. J, M and Z stops.

Under the 18-month full closure option, there would also be a bus service across the Williamsburg Bridge and an M14 SBS across 14th St., with some buses running up to 20th St. to connect to a ferry from Williamsburg.

The M23 SBS and M34 SBS would also be extended to connect to a new ferry — but the amount of extra bus service required prompted Hakin to admit the MTA would need “SBS on steroids to make this work.”

Under a one-track closure, additional buses would also run along 14th St. and between Bedford and Lorimer Sts. in Brooklyn, and the agency is working with the city to figure out whether to install dedicated bus lanes on the Williamsburg Bridge.

The MTA says it will also improve the stations at Bedford Ave. and First Ave., with new elevators and stairs, and a new entrance at Ave. A for the Manhattan stop.

Even though full-fledged work on the tunnel reconstruction won’t begin until January 2019, the MTA says it will pick one of the two scenarios in the next few months, after gathering more feedback from residents in Canarsie and presenting the two options to all affected community boards.

“We’ve got time to do these options right,” said Prendergast.

The only audience members who directly opined on the two options — via previously submitted question cards — seemed to prefer the shorter, 18-month closure, which one commenter referred to as the “preferred first option.”

After a similar town hall in Brooklyn last month, many had perceived the agency to be not-so-secretly favoring the shorter option, but the top brass were careful to avoid showing any preference last week.

“The first option, not the preferred one,” MTA Chief of Staff Donna Evans was quick to correct the commenter.

“People say, ‘You’re probably preferring one option,’ ” added Prendergast later. “No; we’re having a dialogue. We need to make sure we understand the pros and cons of these options.”

But no matter which scenario is picked, the transit honchos admitted that it wouldn’t be an easy burden for straphangers.

“This is going to be a hardship,” Hakim said. “But at the end of the day, we need to get it done.”