By Mary Reinholz

Two days after an anonymous jury convicted her in federal court of aiding terrorism by conveying messages from her imprisoned terrorist client Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman to an Islamic network in Egypt, Downtown activist lawyer Lynne Stewart took the cold evening air in Manhattan with her husband Ralph Poynter. The couple stopped at Revolution Books on W. 19 St. to listen to an author discuss an uprising in Nepal.

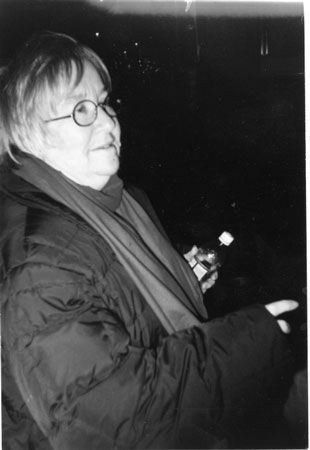

“Like I told The Times, I feel like a truck hit me,” said Stewart, 65, bundled up in a black coat and red stole as she paused to let a reporter snap pictures of her outside the bookstore, which forbade taking photographs inside. She held a bottle of Schweppes seltzer water and smiled wanly.

But during a subsequent Valentine’s Day telephone interview from her Lower Broadway office, across the street from her former headquarters, which she was required to leave eight months ago when a jittery landlord refused to renew her lease “for any amount of money,” Stewart resumed her characteristic feistiness. She dismissed her five-count Feb. 10 conviction as the work of “paranoid” prosecutors and jurors who went along with a government line “like little tin soldiers.”

“They basically strung together their own paranoid view of the world,” Stewart said of the prosecution team, one of whose members, Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew Dember, had claimed in his summation that Stewart “secretly” hoped to overthrow the Egyptian government by issuing a press statement for the blind and diabetic sheik, a fundamentalist Muslim cleric, in defiance of jailhouse rules. Stewart contended that the jurors who convicted her “wanted to believe” what the government charged in her case, like the general public “wanted to believe there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. The government must be right when they said there were W.M.D. The government said we were terrorists and that must also be so,” she added sardonically, referring to herself and two co-defendants, Arabic interpreter Mohammed Yousry and Ahmed Abdel Sattar, a paralegal for the sheik.

Both men were also convicted on all counts following a closely watched post-9/11 trial that spanned more than seven months and ended after 12 days of jury deliberation before U.S. District Court Judge John G. Koetl at Foley Sq.

The verdict shocked and disappointed Stewart and her supporters, some of whom had attended her trial nearly every day.”The motivating factor would have to be a terrible fear of the government,” Stewart continued in evaluating the jurors’ decision, noting that three of the women jurors “wept throughout the entire verdict. This tells me they were unhappy with the verdict but didn’t have the spine to stand up” to the other jurors.

Sattar, a former Staten Island postal worker who had made thousands of government-tapped telephone calls to the sheik’s followers, was found guilty of the most serious charges and faces the prospect of life imprisonment. Yousry faces 20 years in jail. Stewart, who could spend 30 years in prison after sentencing, remains free on a $500,000 bond put up by her three adult children after her 2002 indictment, but must remain in New York. She was unable to explain why prosecutors permitted her stay out of prison, claiming she expected to be “locked in irons” after being pictured in court as “the Devil incarnate.” Herbert Hadad, a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in New York, Southern District, acknowledged the arrangement, but would not comment on details.

As for her current plans before sentencing on July 15, Stewart said: “We’re going to organize” a letter-writing campaign.”We have just been overwhelmed, deluged really, with support from people stopping me in the middle of the street and writing e-mails.” Stewart noted that when she and Poynter went into a Village store to get some valentines “people came up and said, ‘We’re with you.’ There are people all over the country who thought I was going to win and now they’re fighting mad. We’re going to make a big push. We’re hoping to get 100,000 letters” to present to Judge Koeltl, she said.

Stewart also is “crafting an appeal” with her lead defense attorney Michael E. Tigar, who will file motions before the judge late in March, Stewart said, calling to set aside the verdict and schedule a new trial. She is more optimistic for success in sentencing, claiming there are “new sentencing rules” and Koeltl is no longer bound by federal guidlines on sententencing in her case.

Federal prosecutors successfully argued that Stewart defrauded the U.S. government and aided Islamic terrorists when she released a May 2000 press statement to a Reuters reporter in Cairo on behalf of Abdel Rahman, after first signing an agreement that severely limited his communication to the outside world. In the press statement, the sheik announced to fellow members in the militant Islamic Group that he was withdrawing his support for a ceasefire with the Egyptian government. He is currently serving a life sentence at a U.S. prison hospital facility for inciting the first attacks on the World Trade Center in 1993 and conspiring in a thwarted conspiracy to bomb New York City landmarks.

Alberto Gonzales, President Bush’s designated attorney general suceeding John Ashcroft — who had flown from Washington to announce Stewart’s 2002 arrest and indictment — said the convictions “send a clear, unmistakable message that this department will pursue both those who carry out acts of terrorism and those who assist them with their murderous goals.”

Stewart, who was Abdel Rahman’s trial lawyer and continued visiting him after his 1995 conviction, said the government’s claim that she was engaged in a conspiracy with Islamic fundamentalists was based mainly on “just talk” secretly monitored by prosecutors. She adamantly denies she’s a terrorist, noting that no terrorist violence resulted from her conduct. Stewart added she has no Islamic leanings either:

“I’m no fundamentalist, that’s for sure. And I have a fairly strong aversion to most religions. When I represented Sammy the Bull,” she went on, alluding to her former Mafia turncoat client, Salvatore Gravano, prosecutors “didn’t say I was a murderous moll from Bensonhurst.”

In issuing the press statement for Abdel Rahman, Stewart said she was simply acting as a zealous advocate for the ailing sheik, hoping that the publicity she provided him would ease his isolation in jail and facilitate his transfer to a prison in his native Egypt.

As for breaking jailhouse rules, Stewart claimed: “I never felt I was breaking anything. I thought they could cut me off from the client,” she acknowledged of the Bureau of Prison rules known as Special Administrative Measures or SAMS that she signed under both the Clinton and Bush administrations. “It said on this piece of paper that breaking the SAMS could result in being cut off from visits. Neither Reno nor Ashcroft threatened any kind of prosecution,” she added, referring to former Attorney Generals Janet Reno and Ashcroft when they headed the U.S. Justice Department.

New York’s legal community appears to be divided on whether Stewart’s conviction sends a chilling message to criminal defense lawyers who represent unpopular clients. Some clearly think it does.

“I think the jury verdict, like the decision by the government to charge Lynne Stewart, will have an enormously chilling affect on the abillity of lawyers to take on unpopular clients,” said Downtown lawyer Daniel L. Alterman, a former president of the New York City chapter of the National Lawyers Guild and an adjunct professor at New York Law School who has taken on constitutional cases. “They will perceive that their actions will come under greater scrutiny by the govenrmment and hit them where they don’t want to be hit — in the public eye and the pocketbook.”

Michael G. Dowd, a Manhattan criminal defense lawyer who has represented defendants ranging from battered women who have killed abusive husbands to accused gunrunners for the I.R.A., said he felt “physically ill” over the verdict and predicted that it “will curtail really good advocacy. It means there’s a new set of rules.This is about politics and it smacks of the kind of fear I would have imagined was from the McCarthy era but am too young to remember,” added Dowd, whose license was suspended in the 1980s for three and a half years after he acted as a whistle blower in the Parking Violations Bureau scandal. Stewart faces automatic disbarment because she’s been convicted of felonies.

Martin Stolar, who is the current president of the New York City Chapter of the National Lawyers Guild and a strong supporter of Stewart, said she had an obligation as a criminal defense lawyer for the sheik “to do everything she could to keep him in the public eye, rather than having him locked away in the dark hole the government put him in. So it makes me a little nervous because I do these kinds of cases and feel I have a target on my back.”

In response to the verdict, on Feb. 17, Both Stolar and Stewart will be among the speakers at a Guild-sponsored “Day of Outrage” forum starting 7:30 p.m. at the Community Church of New York, 40 E. 35th St., between Park and Madison Aves.

But other legal minds in the city are clearly not outraged by Stewart’s legal problems, claiming she crossed a professional line.”I’m not troubled by the verdict,” said Stephen Gillers, a professor at New York University School of Law who specializes in legal ethics. “A bar license is not a license to violate the criminal law,” he said. “I don’t know whether or not Stewart did what the government said she did, but its evidence did not merely show zealous behavior by an aggressive lawyer. Defense lawyers who fight hard for their clients are not threatened from this prosecution or verdict.”

Former Mayor Ed Koch, who now works for a New York law firm, said he “agreed with the verdict” and contended the jury did a “splendid job.” He said Stewart had “an obligation under the law” to abide by the prison agreements she repeatedly signed. “She was convicted by a jury who had the facts before them,” he said. “Her defense is that she was immune to such charges because she was a lawyer. I think she violated her responsibility as a lawyer and as an officer of the court.” Koch said he “wasn’t going get into details” about the government’s charge that Stewart participated in an Islamic conspiracy “because I wasn’t in the courtroom.”

Ron Kuby, the radical lawyer and radio talk show host who briefly represented Sheik Abdel Rahman with the late William Kunstler in the 1990s, said the jurors who convicted Stewart were clearly not “drawn from the ranks of those activists steeped in the robust tradition of political dissent. Their view was more narrow — lawyers, of all people, should know where the line is drawn and should not cross it,” he said. “We are expected to know exactly what is and what is not permissible. In the context of Lynne’s case — a radical lawyer in the post-9/11 era — trying to explain not only why her actions were justified, but why they were necessary to uphold the liberty of us all — it was just not going to fly.”

Some of Stewart’s friends who are not lawyers took a decidedly earthy view about her conviction. “It sucks,” said Brooklyn prankster Aron Kay, a Yippie known for splattering political enemies with pies. “It’s a prelude to a police state.”

Lynne Stewart outside Revolution Books — after hearing a talk on an uprising in Nepal — two days after her conviction on charges of aiding terrorism.