It is one of the largest research collections dedicated to Black history in the world. Adorning its walls are artwork and films telling the stories of the African diaspora. The ashes of the poet Langton Hughes lay buried beneath the lobby floor.

The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture memorialized its centennial this year, a testament to the temple of Black history that houses over 11 million items throughout its storied reading rooms. The moment is celebratory for the Schomburg as it reflects on a century of empowering Black voices and educating people from around the world — even amid the Trump administration’s funding cuts to libraries and threats to programs that teach Black history.

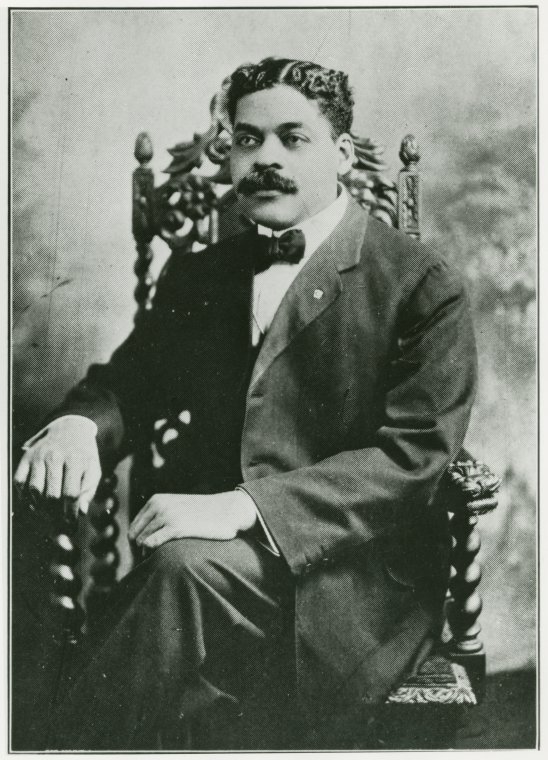

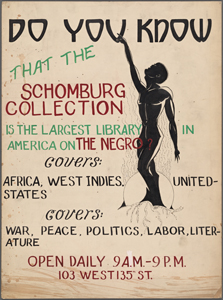

The moment that the famed Afro-Latino bibliophile Arturo Schomburg sold his collection of books, manuscripts and artifacts to the NYPL’s nascent Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints — May 26, 1926 — is etched into the history of New York’s libraries. The division, the forerunner to the Schomburg Center, was only a year old at the time, filling one floor of the 135th Street Branch Library with grants and loans from Black collectors. Schomburg’s collection gave the library a much-needed boost, propelling it into international recognition.

A century later, the Schomburg Center — a sprawling building that subsumed and expanded on the original branch, becoming one of three NYPL research libraries — remains a cultural mainstay of Harlem, New York City and the United States.

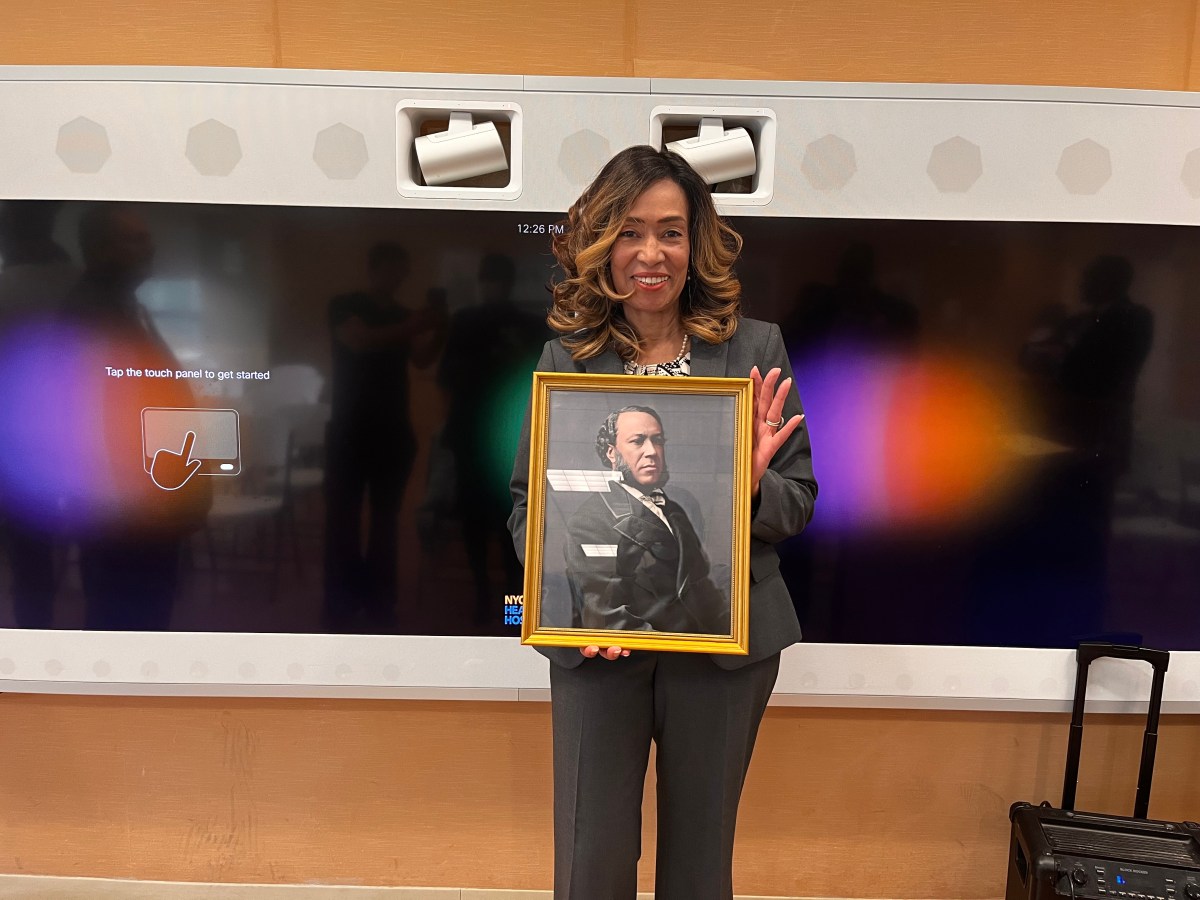

“The archive is a living thing because it continues to expand — the archive is in conversation with itself,” K.C. Matthews, the center’s deputy director of operations and external engagement, said in an interview.

The 100-year celebration kicked off on May 8 — the day the original NYPL division launched in 1925 — with a series of literary and cultural events that united writers, researchers, former Schomburg directors, journalists and artists. The day culminated in a lively block party that featured the rapper Slick Rick and the DJ D-Nice.

Beginning a full year of festivities, the event invited guests to browse the same halls that acclaimed intellectuals such as James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston and Malcolm X once frequented. A new exhibition, open through June 2026, tells the Schomburg’s own story through its collections and documentation.

“Whenever we’re telling the story about who we are, we refer to the collection so that it’s not just telling a tale, it’s not just telling stories, but there is some documentation,” Matthews said.

“Our story is about what’s in the collection,” Matthews added. “Our story is about Black history and culture.”

A century-old vision

Schomburg, the library’s benefactor and longtime leader, was once told by his fifth-grade teacher that “Black people had no history, no heroes, no great moments.” The statement inspired a lifelong dedication to finding “vindicating evidences” to the contrary, he later wrote.

Schomburg encapsulated his guiding belief in a 1925 essay: “The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.” He chronicled Black intellectuals and demonstrated the richness of Black culture, concluding that Black people deserve “the same values that the treasured past of any people affords.”

The current exhibition, titled “100: A Century of Collections, Community and Creativity,” puts Schomburg’s vision on full display, hosting the works of Black luminaries throughout U.S. and world history.

The poems of Phyllis Wheatley, the first African American to publish a book, lay alongside the poems of Maya Angelou and modern emblems of Black culture throughout the exhibition. Around them is a lattice structure, evoking bookshelves, that tell the Schomburg Center’s own history, including posters from its past and portraits of venerated leaders.

Ornamenting one of the walls is a list of some of the famous people and organizations whose collections the Schomburg Center has held, including civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph and Alpha Kappa Alpha, the first sorority founded by Black women.

“I think we’ve proven that teacher wrong,” said Brent Reidy, director of NYPL’s research libraries, at the centennial kickoff event.

Matthews said Schomburg’s love for learning and thirst for knowledge about his own people enabled the center to grow.

“It’s the story of the curiosity of this boy that turned into a man who built our collection,” Matthews said. “And it’s that vision that we still follow today: We are still collecting and making sure that the richness of Black history and culture is made public.”

Core to Schomburg’s legacy, Matthews said, is that the collection is always public — anyone with an NYPL card can access the archives.

“The idea that his collection came to a public library here in Harlem was not an accident. That’s what Arturo wanted,” Matthews said. “That’s what the people in Harlem wanted.”

Linking community and history

The Schomburg Center’s story is entwined with that of Harlem, Black America and the United States as a whole. From the outset, it was a core part of the Harlem Renaissance, playing host to writers, artists and intellectuals who read, researched and collaborated there.

And dating back to the original division at the 135th Street branch, Harlem was involved in the center’s future.

“We would not exist if it weren’t for the community here in Harlem that was actually coming to this library at 135th Street because they wanted to know more about people of African descent,” Matthews said.

Community advocacy led to the first Black librarian and the first Spanish-speaking librarian in the NYPL system, both based at 135th Street.

“Black librarianship developed here in Harlem,” Matthews said. “It’s not just what you collect, but who’s collecting and how you’re cataloging them, and how you’re representing them to the public so they can find what they want. That’s Black librarianship.”

Throughout the 20th century, the Schomburg was a centerpoint of cultural expression, artistic exploration and community resilience. Hughes, the icon of the Harlem Renaissance, often visited the center, his contributions immortalized through a cosmogram in the lobby floor that contains his ashes. The American Negro Theater, where many mid-century performers got their start, lived in the basement of the library in the 1940s.

Being steeped in that history, Matthews said, allows you to develop your own sense of the world.

“We want you to find your voice by seeing and hearing and experiencing the voices of the greats that have come before you,” Matthews said.

He compared writers to athletes, dancers and musicians, who often watch others in their field to learn. Writers, he said, do the same — using an archive.

Alongside its research collection, the Schomburg hosts public programs, including events and discussions, that aim to connect the library to Harlem and New York City while inviting members of the public to engage with the collection.

Matthews said the public programs are a “major part” of the Schomburg, and they are even how he found his job: He reconnected with the center after over a decade through an event, “fell in love” with it and applied for a position a few years later.

In September, the center will present the first annual Jean Blackwell Hutson award, commemorating the former Schomburg chief who solidified the center’s position, to Carla Hayden, the first woman and first Black person to be appointed Librarian of Congress. (Hayden was removed from office by President Donald Trump in May as he escalated attacks on the Library of Congress’s independence, though Matthews said the award was decided beforehand.)

In a panel discussion during the centennial kickoff in May, former Schomburg director Khalil Gibran Muhammad, who led the center from 2010 to 2015, said he received criticism during his tenure that the Schomburg had lost touch with the broader community and modern issues.

Muhammad said he worked to ensure the Schomburg contributed to national conversations surrounding racism to “close the gap” between the center and the community, including by starting a youth program and connecting with the Black Lives Matter movement.

For Muhammad, “artistic and activist knowledge” is the goal of the Schomburg Center.

Resilience and lifelong learning

The Schomburg’s commitment to its community and celebration of its history come amid attacks from the federal government on library systems and independence, especially research on historical injustices.

The Trump administration recently threatened a review of the Smithsonian Institution to ensure it aligns with “American ideals.” Trump has also attempted to roll back federal grants for libraries.

“Our whole ecosystem is under attack,” Muhammad said.

While federal funding makes up only a small portion of the NYPL’s budget, Matthews said Trump’s assault on libraries was an affront to knowledge.

“It’s the attack on knowledge, it’s the attack on primary sources, the attack on facts, that is the most dangerous and most difficult thing that we’re all experiencing,” Matthews said.

Matthews said anyone interested in preserving a commitment to history and fact should dedicate themselves to research and learning.

“This is a lifelong pursuit,” Matthews said. “If you want to learn more about your history and your culture, there’s something to learn every single day.”

Matthews, who describes himself as a “perpetual student,” said working at the Schomburg is like “being a kid in the candy store.”

“I get to learn something new every day,” Matthews said. “I get to learn something new about myself and my history and the people that shaped that history.”

Matthews said he often encounters lifelong Harlemites who are embarrassed to be visiting for the first time. He immediately tells them to never feel remorse.

“Don’t ever feel bad about learning something for the first time,” Matthews said. “Be glad you’re learning it right.”

When you sit for a moment in the Schomberg Center, the reading rooms are generally quiet with the energized hum that libraries have, the air filled with rustling pages and scribbling notes. The artwork and books that line the wall tell the story of the Schomburg and Black America — which are often one and the same — evoking a legacy of millions of visitors that came before, from tourists to researchers to some of the greatest intellectual minds of the past century.

In many ways, the national threats to libraries and research institutions make the Schomburg Center’s mission ever more important, Matthews said.

“We’re not taking books off of our shelves, and the Schomburg Center is not changing what we collect, what we preserve or that we’re making it public for anyone who wants to view it,” Matthews said. “That’s not going to change, has never changed for the first 100 years and won’t be changing anytime after.”