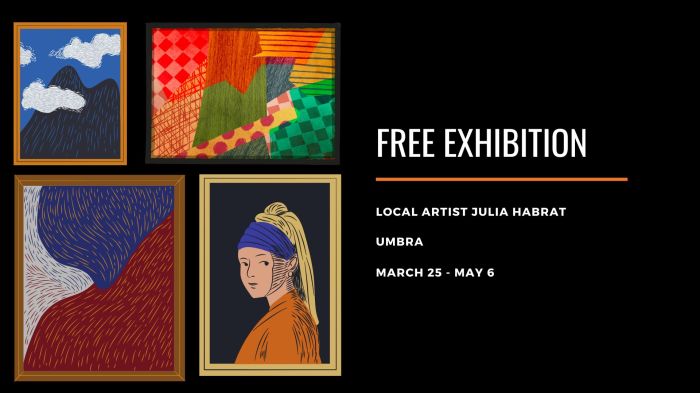

Locals complain that the scaffolding around 20 Exchange Pl. has been up for more than four years.

BY YANNIC RACK |

Residents and business owners in Lower Manhattan are looking to Albany for relief from the plague of sidewalk sheds that have encrusted so many Downtown blocks and often linger for years whether they’re needed or not.

A set of bills introduced by state lawmakers aims to kick the zombie sheds to the curb by requiring building owners take them down unless work is ongoing, rather than leave them looming unnecessarily over the sidewalks, where they become a nuisance for those underneath.

“Your business is failing, because you’re literally left in the dark. It’s terrible,” said Ann Benedetto, whose boutique in Tribeca has been shrouded by scaffolding for months at a time over the past few years.

Benedetto estimates that the sidewalk shed around her shop, which stretches all the way around the corner windows she pays so much rent for, has cost her more than $200,000 in revenue since 2013.

And Benedetto isn’t alone in her frustration. Community activists around Downtown cite several sidewalk sheds that have been up as long as four or five years.

“The situation is out of control. I’ve been following this for a long time,” said Arthur Piccolo, the chairman of the Bowling Green Association.

Piccolo said he surveyed the Financial District to flag the worst offenders — such as 20 and 40 Exchange Pl., which have had scaffolding up for around four and five years, respectively.

“There are eight properties within a couple-hundred yards of Wall and Broad Streets that have been up for at least three years,” Piccolo said. “It’s egregious.”

Now the outrage is being heard all the way in Albany.

“We hear complaints about it fairly frequently, both from commercial enterprises and from residents,” said Lower Manhattan Assemblymember Deborah Glick, who co-sponsored the shed-shedding bill.

The scaffolding not only blocks the view of businesses, but over the long term, the sheds can collect trash, create hazards for pedestrians and erode local quality of life, she said.

“It creates a dark area, debris can accumulate. If it’s not properly lit, it can be a safety concern,” Glick said.

In addition to the unintended consequences, Glick suspects that some persistent scaffolding could even be part of a more nefarious agenda.

“And it does sometimes appear that it is being used as a vehicle for driving either people out of their homes or businesses [into giving up] their lease,” she said.

The bills in the State Senate and Assembly would only allow extensions to sidewalk shed permits if the scaffolding was used for construction work at least 10 days every month in the previous year.

There are currently around 7,700 of the wood-and-steel structures scattered around the city, according to the Dept. of Buildings, which issues permits for scaffolding whenever building owners build, inspect, or make repairs to the façades. And even the city admits that many of the sidewalk sheds have outlived their usefulness.

The Dept. of Buildings recently performed a sweep of all sidewalk sheds in the city and found that more than 150 of them were no longer required, according to a spokesman — and that wasn’t the only problem they found.

“Inspectors looked for safety problems and common eyesores that reduce people’s quality of life, including sheds that haven’t been painted in years or are covered with graffiti, where the lighting is out, or where there are missing boards or structural supports,” he told Downtown Express, adding that inspectors issued more than 600 violations.

The department is currently reviewing the proposed legislation, he said.

But some Downtowners think new state laws won’t make a difference anyway — not least because they would rely on the Dept. of Buildings, which isn’t strictly enforcing the laws already on the books.

“I think, on a practical level, it’s meaningless,” Piccolo said at a meeting of Community Board 1’s Planning Committee on Feb 8. “The state has no enforcement ability — the buildings department will be responsible to enforce this themselves.”

At a meeting of CB1’s Quality of Life Committee last month, members wondered how inspectors could verify that enough work was being done each month, and were also skeptical that the proposed fines for noncompliance — capped at $1,000 — would have any effect.

“That’s a lot for me, but it’s the cost of doing business for them,” said committee member Mitch Frohman. “It’s cheaper for them to pay the fine than to put the scaffolding back up when they need it.”

Glick told Downtown Express that the main purpose of the law was to break the pattern of the Dept. of Buildings simply rubber-stamping repeated extensions for scaffolding permits.

“It’s really a directive to the agency not to just automatically renew these permits,” she said.

For Benedetto, relief can’t come soon enough — no matter what shape or form.

“Anything that causes people to rethink it is a good thing, as far as I’m concerned,” she said of the legislation. “Something has to be done. I’m hanging on by my fingernails.”