By selecting an ordinary manufactured object and declaring it art through context and choice, Marcel Duchamp dismantled the belief that artistic value resided solely in craft or aesthetic pleasure.

The object itself became secondary to the idea that framed it, and in this conceptual relocation art ceased to be defined by the hand alone and became a proposition issued to the mind.

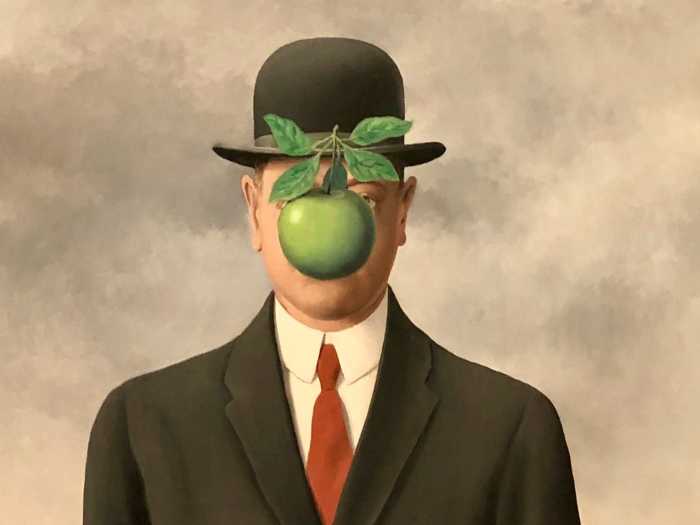

The moment art ceased its sole devotion to visual pleasure and instead began demanding intellectual engagement, the entire architecture of culture shifted. In the early 20th century, a radical inversion took place that moved the center of gravity away from surface and toward thought, away from virtuosity and toward intention, away from what the eye consumes and toward what the mind must confront.

At the center of this rupture stood the readymade, a gesture so deceptively simple and yet so infinitely consequential that its reverberations continue to shape artistic practice more than a century later.

This conceptual turn emerged amid the cultural disorientation of the 1910s and 1920s, when the devastation of World War I gave rise to movements such as Dada and Surrealism, which distrusted reason, celebrated contradiction, and sought to expose the absurd undercurrents of modern life.

Within this climate, Duchamp’s work did not merely rebel; it reorganized. His interventions were neither nihilistic nor capricious, but exacting, ironic, and deeply disciplined, fusing humor, erotic tension, mechanics, and philosophical inquiry into structures that refuse closure. Beauty in his work was not abandoned; it was transposed from retinal seduction to intellectual elegance.

The significance of this shift will be unmistakably on display in 2026 when the Museum of Modern Art presents the most comprehensive retrospective of Duchamp’s work in the United States since 1973.

Spanning painting, sculpture, found objects, kinetic pieces, drawings, and correspondence, the retrospective Marcel Duchamp (on view April 12 through Aug. 15) charts six decades of inquiry, invention, and disruption, contextualizing Duchamp’s legacy not as an artifact of its time, but as a continuing force in contemporary practice.

This retrospective is not a museum event alone; it is a cultural reckoning, one that underscores Duchamp’s enduring relevance at a moment when questions of authorship, materiality, and intentionality have never been more urgent.

Duchamp’s influence extended quietly but decisively into the currents of postwar practice, shaping generations of artists who recognized that art could function as a system, a proposition, or a question rather than a decorative endpoint. Crucially, this methodology never rejected materiality.

Even at its most cerebral, Duchamp’s work remained physically present, whether in industrial porcelain, glass and wire, or found objects transformed through placement and context. His art engages the body as much as the intellect, weaving eroticism, humor, and mechanical metaphor into objects that insist on presence rather than mere appearance.

Marcarson: Conceptualism as material discipline

Within this lineage, Marcarson operates with quiet rigor, extending Duchamp’s logic into a materially saturated present. Marcarson’s practice privileges design over spectacle, structure over flourish, and thought over immediacy. Through recycled materials, repeated forms, and calibrated systems, he constructs environments that resist instant comprehension and reward sustained engagement. The emphasis is not on visual excess, but on how meaning accrues through restraint, repetition, and physical presence.

Marcarson regards material as evidence rather than ornament, allowing the trace of human decision-making to remain visible. This insistence on tactility functions as a refusal of automation, reaffirming the value of judgment, labor, and intention in a culture increasingly dominated by generated imagery. His work does not perform for the viewer; it asks the viewer to participate intellectually and temporally in its completion.

Theaster Gates: Rebuilding meaning through reuse and care

A parallel extension of Duchamp’s legacy can be found in the work of Theaster Gates, whose practice merges conceptualism with architecture, design, and social ritual.

Gates reclaims discarded materials—decommissioned fire hoses, salvaged wood, industrial remnants—and transforms them into sculptural and spatial propositions that speak to history, labor, and collective memory. His work insists that material carries biography, and that reuse is not merely sustainable, but symbolic.

Gates’ conceptual intelligence lies in his ability to design systems that function simultaneously as artworks, civic interventions, and cultural archives. Like Duchamp, he understands that framing is a form of authorship and that value is produced through context rather than surface appeal. His work elevates care, maintenance, and stewardship to artistic acts, reinforcing the notion that construction—both physical and social—remains central to human meaning-making.

Doris Salcedo: Conceptual weight and the politics of presence

The work of Doris Salcedo offers another continuation of Duchamp’s insistence on concept as structure, one forged through emotional and historical gravity. Salcedo’s installations and sculptural interventions employ furniture, concrete, and architectural disruption to give form to absence, grief, and systemic violence. Her work operates at the intersection of conceptual rigor and bodily confrontation, insisting that meaning is constructed through space, memory, and lived experience rather than visual pleasure alone.

Salcedo’s practice underscores a critical dimension of contemporary conceptualism: the refusal to aestheticize trauma and the insistence that material presence carries ethical responsibility. Her work demands bodily engagement, compelling the viewer to navigate disruption, instability, and discomfort as integral to understanding the histories embodied in her materials.

Why this work has become collectible today

The resurgence of materially grounded conceptual art signals a broader recalibration of taste and intention. As digital imagery saturates daily life and artificial intelligence challenges assumptions about authorship, works that bear the imprint of human judgment acquire renewed authority. Conceptualism, when paired with material discipline and design intelligence, offers collectors something increasingly rare: irreducibility.

These works cannot be flattened into screens or endlessly reproduced without loss. They require space, context, and sustained attention. They reward intimacy rather than exposure. Collectors drawn to this lineage are not chasing novelty but seeking alignment with objects that sharpen perception and sustain intellectual and emotional engagement over years and decades.

Duchamp anticipated this moment with unmistakable clarity. He understood that art’s greatest power is not its ability to please, but its capacity to reorient thought, to destabilize habit, and to eroticize intelligence itself. In returning to Duchamp, through events such as the 2026 MoMA retrospective and through contemporary practices that extend his methodology, we reaffirm the enduring importance of conception, construction, and critical thought in an increasingly automated world.

This is why Duchamp matters today. His work teaches us that art is not an ornament of life but a method for understanding it—one that insists on intelligence, presence, and the enduring value of the human hand. In engaging with such work, we discover not only how to see art, but how to think with it.