To speak of Wilfredo Lam is to confront modernism at its most unfinished edges. His work does not sit comfortably inside art history; it presses against it, interrogates it, and ultimately expands it.

Seeing Lam now, in the context of a major institutional presentation at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in “When I Sleep, I Dream,” feels less like a retrospective and more like a recalibration. This is modernism reclaimed, corrected, and spiritually recharged.

Lam’s impact lies in his refusal of singular origin. Born in 1902 in Sagua La Grande, Cuba, to a Chinese immigrant father and an Afro-Cuban mother, he inherited a plural visual and spiritual vocabulary from the start.

From his father came an understanding of objects as vessels, of line as philosophy, of restraint as power. From Afro-Cuban cosmology came ritual, invocation, and the inseparability of body and spirit. These influences did not coexist politely in his work; they fused. Lam’s paintings are not hybrids for novelty’s sake, but deliberate syntheses of diaspora, migration, and survival.

His time in Europe sharpened his formal intelligence without diluting his purpose. Cubism and Surrealism offered tools, not direction. Lam understood that European modernism fractured form but failed to reckon fully with colonial violence and spiritual erasure. His response was neither imitation nor rebellion, but transformation. He rebuilt abstraction from the inside out, insisting that Black and Caribbean identity could not be rendered through Western naturalism without loss. Abstraction became his instrument of truth.

Two works in particular struck me with uncommon force.

The Jungle (1943) remains one of the most psychologically charged paintings of the 20th century, and encountering it in person feels almost confrontational. Sugarcane stalks rise like vertical bars, compressing space and collapsing figure into ground. Elongated bodies multiply and entangle, part human, part vegetal, part spirit. Faces mask themselves. Limbs stretch beyond anatomy into intention.

This is not a depiction of a place, but a condition. Plantation history is transfigured into psychic architecture, beauty sharpened into indictment. The work tightens around the viewer, leaving no distance for comfort. It does not narrate colonial trauma; it makes it palpable.

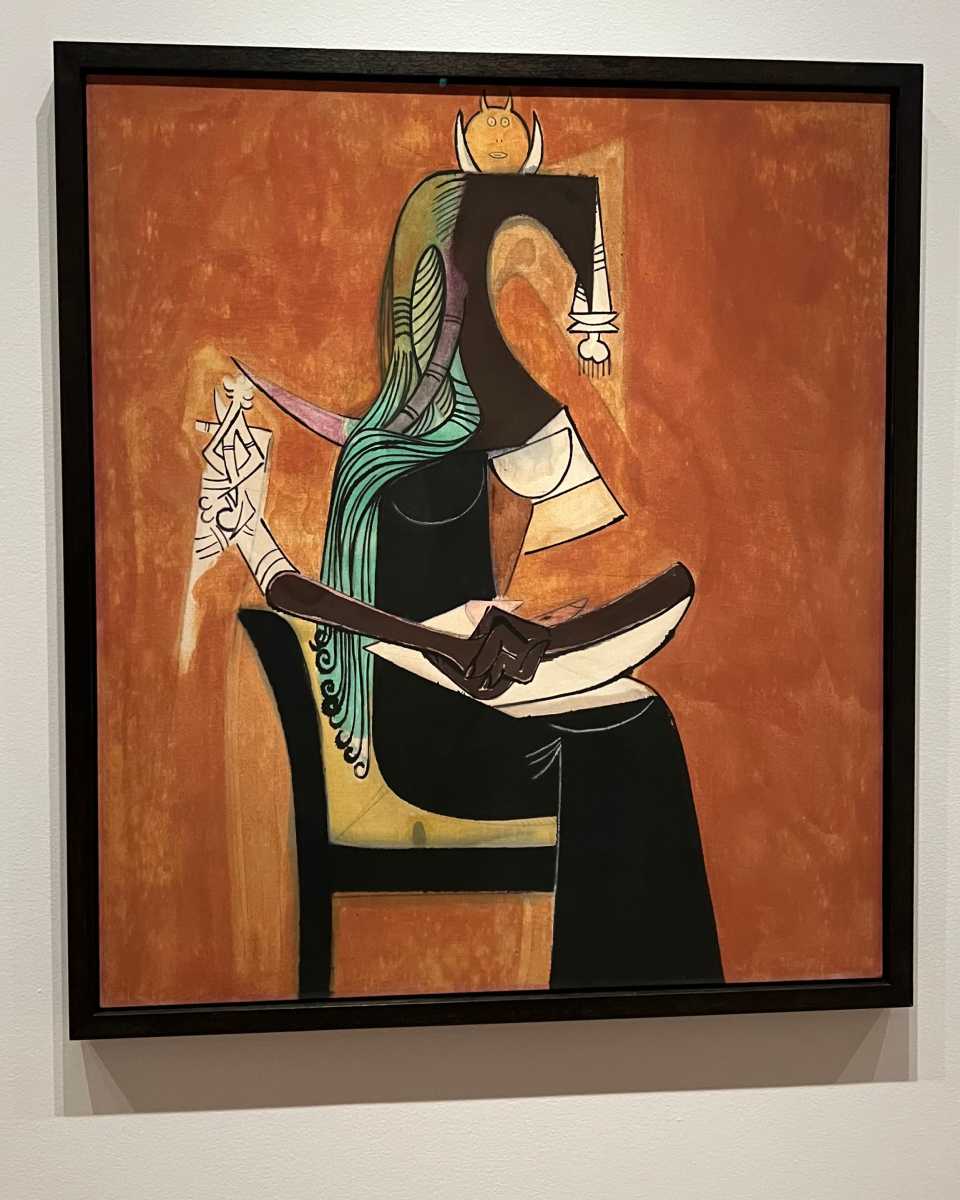

Je Suis (1949) offers a different register, though no less commanding. The title alone — I am, in French —reads as a declaration, metaphysical and political at once.

Created in the postwar moment, the painting asserts existence against systems designed to erase it. The figures remain abstracted, unresolved, yet sovereign. They do not plead for recognition. They state it. Space opens slightly compared to The Jungle, allowing breath without ease.

The palette remains disciplined—shadowed blues, earthen greens, bone whites—colors that seduce rather than overwhelm. The muted chromatic restraint does not dull the mind; it sharpens it, drawing the viewer inward toward sustained contemplation.

Together, these works reveal Lam’s extraordinary control of form and meaning. Elongation becomes refusal. Abstraction becomes lineage. Color becomes the seduction of the intellect. What unfolds is both an internal excavation—psychological, intimate—and an external one—historical, corrective. This dual movement is rare. It is also transformative.

The importance of seeing Lam in an institution like MoMA cannot be overstated. Representation here is not symbolic; it is structural. Lam’s presence reasserts that modernism was never singular, never exclusively European, never spiritually neutral. It was diasporic, contested, and deeply entangled with power. His work does not decorate the museum; it reorients it.

This exhibition is not passive viewing. It demands attention, stamina, and openness. It rewards the viewer with the rare sensation of being intellectually challenged and emotionally undone at the same time. Art like this does not simply reflect history; it alters how history is held.

Go and see it. Stand in front of these works. Allow them to work on you. Institutions matter most when they make space for art that transforms consciousness, and Wilfredo Lam does exactly that—elongated, sovereign, and enduring.

For more information, visit MoMA.org.