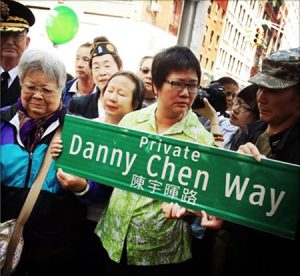

After the memorial service, attendees marched to the stretch of Elizabeth St. that was co-named for Pvt. Danny Chen in 2014.

Pvt. Danny Chen volunteered to serve his country, but his fellow soldiers’ bullying drove him to suicide in 2011.

BY COLIN MIXSON

Chinatown residents gathered in memory of Pvt. Danny Chen on Sunday, the fifth anniversary of his death, paying tribute to the hometown soldier who was driven to take his own life at the age of 19 after enduring weeks of brutal hazing at the hands of his fellow soldiers.

Chen’s family and friends were greeted at the memorial by community members, politicians, veterans, and dozens of unrelated well-wishers, many of whom were drawn to the commemoration by nothing more than the powerful and painful story of the soldier’s tragic death.

“I think the word is spreading,” said Councilwoman Margaret Chin, a longtime advocate for the Chen family who was instrumental in getting a section of Elizabeth St. co-named for the soldier in 2014. “From [Sunday’s] program there were college and high school students — many who didn’t know what happened to Pvt. Danny Chen, and one student who spoke about seeing his street sign, and how that lead to doing research about who he was and what happened to him.”

This year’s remembrance at PS 130 marked the fifth annual memorial since Chen’s body arrived from Afghanistan in 2011, his lifeless six-foot form weighing a mere 100-pounds and covered in bruises.

At first, Chen’s family was told by the Pentagon only that Chen had been shot, and it wouldn’t be until weeks later that the trickle of details regarding the circumstances of his true fate coalesced into a tale of constant torment, not from foreign enemies, but from his comrades in arms.

Over a period of six weeks, Chen was assailed on a daily basis with an endless barrage of ethnic slurs and physical tortures, including excessive guard details, forced exercises, and beatings.

On Oct. 3, 2011, the day Chen shot himself to death, his fellow soldiers forced him to crawl across a football field’s length of gravel, pelting him with rocks along the way.

The honorary street sign placed at the corner of Elizabeth and Canal Sts. in 2014 has become a rallying point for those wanting to do justice for Pvt. Danny Chen by preventing the often race-based bullying still endemic in the armed forces.

And it was only through the tireless advocacy of the Chinatown community and groups such as the New York chapter of the Organization of Chinese Americans — which organized rallies, gathered petitions, and arranged meetings between the family and military brass — that the army finally agreed to charge Chen’s tormentors for crimes related to his death.

Even then, the greater charge of manslaughter was dropped, and many felt the punishments meted out to the eight soldiers convicted of driving Chen to suicide fell far short of Justice, according to the former president of OCA-NY.

“The punishments were paltry,” said Elizabeth OuYang. “Four spent time in jail, but not for longer than six months.”

Family members and advocates host the annual memorial not only to honor Chen’s life, but to also raise awareness of the need for military reform and inform parents of the brutal trials that sometimes await minorities entering the armed services, according to one community leader and long-time advocate for Chen and his family.

“The memorial reminds people of what happened and why we need to say it’s not about the past,” said Wellington Chen executive director of the Chinatown Partnership. “Would you like your child to be subjected to something like this?”

At the memorial, community members listened as Congresswoman Nydia Velazquez and Councilwoman Chin spoke of Chen, while a representative of the Army spoke of new training procedures for officers designed to prevent the type hazing that lead to Chen’s death.

Kids ages 3–4 from the Head Start pre-school Chen attended in his youth sang “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” while holding up an image of the late soldier. Famed composer Huang Ruo appeared at the memorial accompanied by a soprano singer, who sang a lullaby Ruo wrote for an opera about Chen.

“It was beautiful,” said OuYang.

Chen’s cousin, Banny Chen, also spoke at the memorial, describing his cousin as just an ordinary kid whose life was destroyed for no reason other than his race.

“If I were to group Danny with a bunch of other young men, he would not stand out at all, since he was so ordinary to me,” said Banny Chen. “Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case for him in Afghanistan. To his platoon leaders, he was different because of his race, and because he appeared weaker.”

After the memorial program had concluded, the gathering sallied out in a procession to Elizabeth St. near Canal St., to the street sign honoring Chen’s memory, and where Danny’s cousin Ada Chen beat a drum 24 times, one beat for every year Danny would have lived by now had he not been driven to suicide.

“It was very powerful,” said OuYang.

Even five years later, dozens of members of the Chinatown community turn out for the annual memorial for Pvt. Chen — to honor his memory, and to call for military reforms to prevent the sort of bullying that drove Chen to suicide while fighting for his country in Afghanistan.