By Stephanie Buhmann

Lynn Hershman Leeson explores media, fantasy and Manet

Over the past 40 years, Lynn Hershman Leeson has explored empowerment and freedom of speech in a wide range of media, including photography, film, sculpture, performance, and installation. A pioneer in the use of new technology, she has extensively explored the roles of women as assigned by society, and is working on a feature-length documentary about the revolutionary feminist art movement that depicts what women endured in order to display their works.

As an extension of her activisism against censorship, she recently filmed “Strange Culture,” a docudrama starring Oscar-winner Tilda Swinton focusing on the arrest and criminal charges against internationally acclaimed bio-artist Steve Kurtz. In May 2004 when Kurtz’s wife died of heart failure while sleeping, police deemed Kurtz’s art, which then examined the risks of genetically modified foods, as suspicious and notified the FBI. Within hours he was detained as a suspected bio-terrorist. For four years, Kurtz was awaiting trial for possession of biological materials that were freely available online. On April 21, 2008, Kurtz was finally cleared of charges for mail and wire fraud. In a most urgent and artistic manner, Hersman Leeson’s “Strange Culture” examines the danger of the government widening its scope and definition of illegal activities.

In addition to having works in the curated group show “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution,” hosted by P.S. 1, Hershman Leeson is now showing a new project at bitforms gallery. The works in “Found Objects” were inspired by Edouard Manet’s notorious portrait of a prostitute entitled “Olympia” (1863). Hershman Leeson translates the painting into sculpture with the help of a custom-made, life-size doll, onto which parts of Manet’s painting are projected, exploring society’s ongoing objectification of women and the fantasies that are entailed. While Manet’s portrait shocked his contemporaries as it transformed Titian’s Venus of Urbino into a real woman, who looked straight at the viewer with an unwavering and unapologetic glance, Hershman Leeson finds new provocation in the artificiality of her subject.

Over the course of seven months, she assembled various doll parts to evoke an image that could closely resemble Manet’s painting. Taking on the famous pose of Manet’s subject, Hershman Leeson’s Olympia reclines on a chaise lounge as the projections of the painting become imprinted on her plastic skin. It is as an image that seems to imply that when it comes to women, the prejudices and restrictions of the past have not been shed. Though prostitutes might not have the same shock value today as in the 19th century, the airbrushed and omnipresent images of fashion models or celebrities is not far from the doll’s artificiality. In both cases, women resemble perfected ready-mades that can be appropriated to any desire or fantasy.

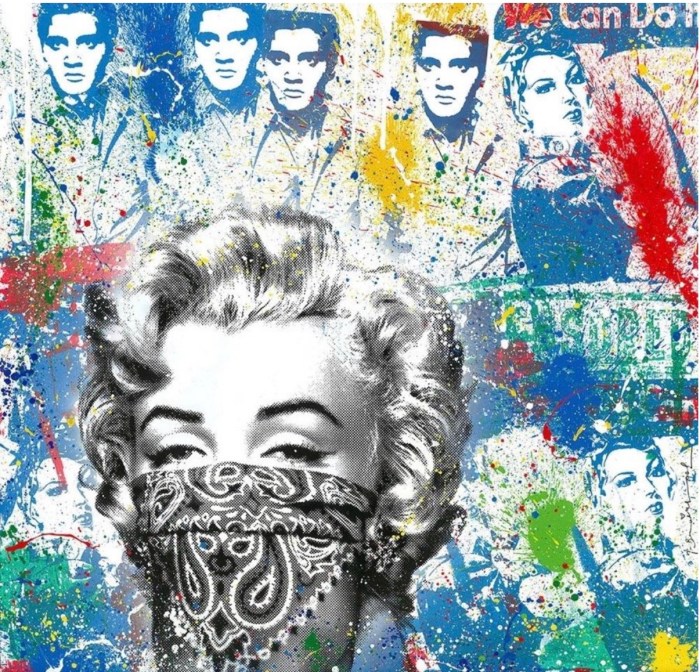

Photo by John Berens Courtesy bitforms gallery, New York

Lynn Hershman Leeson’s “Olympia: Fictive Projections and the Myth of the Real Woman” (2007-8)

“Found Objects” relates to Hershman Leeson’s past investigation of artificial women, such as the “Roberta Breitmore” project from the 1970s. From 1971-78, Hershman Leeson lived part time as the fictional character Roberta Breitmore, a recent divorcée in San Francisco. Her immersion in the role went as far as developing particular speech patterns, handwriting, and to obtain credit cards, a driver’s license, checkbook, and eventually a separate apartment in Breitmore’s name. Meeting at bitforms gallery shortly before the opening of “Found Objects,” Hershman Leeson discussed the show as well as her earlier and future work.

Why Olympia and why now? Do you want to reach out to a younger generation of women to make them reflect on the image of women as portrayed in society?

Well, my work has, for 40 years, been about projected fantasies of women and how the media treats them. With Manet, some people felt that he identified with this prostitute. The painting caused such a scandal. Now that you can buy even single body parts online, women really have become even more objectified. You can go to a store on the Internet and buy whatever you need. My Olympia took seven months, because I ordered the eyes, the nose, the skin, to make her look as close to the painting as I could. In other words, you can customize the doll according to what you want and what your fantasy is. I think that art historically, and through the media, we have been programmed to look at a version of Manet’s “Olympia” but if you look up the painting online, you get all these different versions of her. Nothing is true. It is all fiction—both the projections as well as who we are.

I am interested in the characteristics of the doll. Her perfect artificial skin, for example, relates to the artificial perfection we find in media images of women today, whether through the help of airbrushing or digital manipulation.

Exactly. It is the idea of having different skins and of the media skins we map onto ourselves.

This is an aspect that ties into one of your earlier works, the Roberta Breitmore project.

There are two works focusing on Roberta in this exhibition. I made Roberta in Second Life [a 3-D virtual world on the web that is created by its residents] and then exported her avatar from Second Life into physical presence. I see these kinds of continuations of fantasy dolls. The Olympia doll is very similar to Roberta and the media’s projections of women in the 1970s. It is the study of something that never existed. It exists only by what you presume.

You are known as a pioneer in working with new technology. How do you view the Internet? Do you consider its inherent dangers?

I think of media as being neutral. It is what one does with media that will determine the future. I see it more as a utopian, globally growing mind—a brain, so to speak. Technology today is fabricating something very new, exciting and creative. I like to use technology with positive goals and sustainability, focusing on how it can empower us as a species.

This exhibition also includes photographs of the doll.

There are images when Olympia is in the crate, still wrapped, or one where she has a hand out and a sign is saying, “handle with care warning,” for example. It seemed to me that I was able to find this real state of emotion in this inanimate object. Something she was projecting for the camera, a real feeling. In these images she seems terrified, frightened and vulnerable. But she is not a victim.

Do you think that this body of work is something you might develop further?

Yes. Olympia is number one, but I see other futures for these dolls.

These dolls do not incorporate computer technology.

I have been doing so many works that are interactive and involve really intense cutting edge technology about which you are always worried if it is going to work or going to break. I have several other works I am currently working on that involve state of the art technology. In that sense it was a nice break to deal with the idea of artifice and identity and media without the reliance on some kind of technological tool.

It seems like sequencing plays an important role in your work.

Yes, it is a narrative. Roberta unfolded in time for example, over the course of a decade. And in this exhibition as well, the doll is slowly coming out as herself.

How do you feel about younger artists, such as Nikki S. Lee, who work with the idea of adopting different personalities to explore different female identities in society, and about the fact that their work is considered radical and new?

My work from the 1970’s—the fact that I spent ten years living in part as a different person—was unknown. Then, almost 35 years later someone comes along and claims to be the first to live as someone else and furthermore only lived for the photograph. I think the reason why the Roberta project is not better known is because it was made so early. There were no references yet, so people found it difficult to understand. But Roberta pioneered ideas that paved the way for Cindy Sherman and others. Duchamp and Breton paved the way for me. It’s a process.

What’s next?

I will try to finish my film on the feminist movement by the end of this year, and then I would like to work on a vampire project that deals with aging.